Latin America’s productivity rate is alarmingly low, with the region being four times less productive than the United States, according to a study by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

To put this into perspective, a U.S. worker accomplishes in one hour what it takes a worker in Latin America four hours to achieve.

While Panama has achieved a productivity rate more than 150% higher than the regional average in the past four decades, Venezuela’s productivity plummeted by 50% during the same period. Other nations showing notable growth include Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, and Uruguay, each recording nearly a 50% increase in output. In contrast, countries like Paraguay, Colombia, Chile, Bolivia, and Cuba have shown only moderate improvements.

Even among OECD member countries in Latin America—Colombia, Chile, Mexico, and Costa Rica—productivity remains significantly below global standards. On average, Latin American countries achieve just 41% of the productivity levels seen in other OECD nations. When compared to the United States, the gap widens further, with the productivity rate of these four Latin American OECD members reaching only 30% of U.S. levels.

Labor productivity, the amount of output produced by a worker in one hour, is calculated by dividing a country’s total output (often measured by GDP) by the total number of hours worked by its labor force.

According to the report, this substantial productivity disparity stems from three primary issues: a lack of skilled workers, insufficient integration of technology in production, and inadequate investment in human capital development.

Commodities and Productivity

Among the factors dragging down productivity is dependence on commodities, according to a few analysts cited by Bloomberg Linea in its analysis of the ECLAC report. Mining is all about lifting and shifting. It doesn’t value human talent or require innovative thinking.

“I don’t completely buy this argument,” said Dionisio Chiuratto Agourakis, CEO of JAI, a São Paulo-based company that offers AI support to boost productivity.

Dionisio Chiuratto Agourakis is CEO of JAI, a São Paulo-based company that offers AI support to boost productivity.

“It’s okay to generate income by exporting minerals, but the real issue is what you do with that income. You must invest it in skill development,” he said in an interview with Nearshore Americas.

César Fuentes, Economic Professor at ESAN University in Peru, also endorses Agourakis’s argument.

The substantial revenue generated by the mining industry often diminishes the urgency for governments to invest in knowledge-intensive industries. However, Fuentes argues that governments should allocate resources or offer incentives to promote value-added activities.

“Oil-rich countries like Qatar and the UAE serve as prime examples, actively transitioning from oil-dependent economies to service-oriented ones,” he explains.

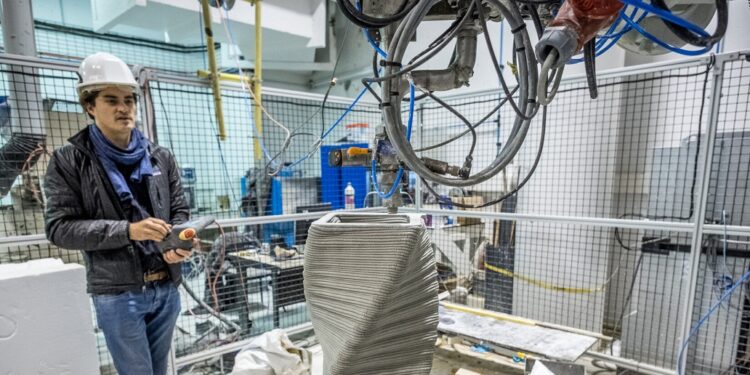

In Latin America, a shortage of skilled workers is reportedly hindering industries from effectively utilizing technology. This issue is compounded by inadequate Information and Communication Technology (ICT) infrastructure, which restricts access to modern tools and innovations.

Agourakis highlights two major challenges in the relationship between technology adoption and productivity in the region.

“First, technology’s ability to improve efficiency relies on established operational processes that can be measured and optimized. Unfortunately, many Latin American companies lack these foundational structures, which limits potential gains from technological solutions,” he says.

“Second, there are practical barriers to adopting technology, such as linguistic challenges with predominantly English-language solutions and cost considerations. Given the relatively lower labor costs in the region, many organizations find it more economical to maintain labor-intensive processes rather than invest in automation.”

The problem with Education

The education sector in Latin America faces numerous challenges, including inadequate infrastructure and poorly trained teachers.

“The educational model prioritizes content delivery over fostering critical thinking or applying a constructivist approach,” says Fuentes.

In Brazil, socio-economic barriers further hinder student learning, according to Agourakis. Many teachers, he notes, often state that “teaching math is secondary” as they focus on addressing students’ basic survival needs.

While private institutions provide better learning environments, they tend to emphasize preparation for university entrance exams at the expense of nurturing critical thinking and creativity. The increasing consolidation of private education has worsened this trend, prioritizing quantitative outcomes like admission rates over holistic student development.

“This approach produces graduates with limited analytical and creative abilities, often confining them to operational roles rather than strategic positions,” Agourakis explains.

Panama’s Success Story

Panama’s economic success is largely attributed to its unique advantages. Guaranteed revenue from the Panama Canal has enabled substantial investments in education and infrastructure. The country’s stable political environment, policy certainty, and relaxed financial regulations have created a favorable climate for foreign investment.

Foreign companies operating in Panama are increasingly adopting advanced technologies, further driving up the country’s productivity rate. As a result, Panama produces goods and services valued at $45 per hour of work—a stark contrast to Haiti, where the figure is less than $4.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=674f3b18d65f42469b6519b75a6f3bc2&url=https%3A%2F%2Fnearshoreamericas.com%2Flatams-productivity-rate-four-times-less-than-the-u-s%2F&c=13277538545840431023&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-12-03 03:28:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.