Michael Froman is president of the Council on Foreign Relations.

More From Our Experts

Technological supremacy is a core pillar of American power. Conceivably, part of the “America First” agenda should be keeping America first when it comes to maintaining that edge.

More on:

Technology and Innovation

We owe much of our unmatched geopolitical and economic heft to transformative research investments spearheaded by the government during World War II and the postwar era. From the early 1940s onward, under the guidance of President Franklin Roosevelt and President Harry Truman’s legendary science advisor, Vannevar Bush, Washington created a powerful apparatus to fund basic scientific research: first, the Office of Scientific Research and Development during World War II and then the National Science Foundation.

The World This Week

A weekly digest of the latest from CFR on the biggest foreign policy stories of the week, featuring briefs, opinions, and explainers. Every Friday.

The ensuing research gave birth to the definitive technologies of the twentieth century, including the Internet (through its precursor, ARPANET), radar, atomic fission, and the techniques essential to the mass production of antibiotics. Thanks in no small part to these breakthroughs, the United States triumphed in two existential wars, first against the Axis powers and then in the Cold War against the Soviet Union—to say nothing of the benefits reaped by humankind.

As he outlined in his 1945 treatise, “Science—The Endless Frontier,” Bush sought to mobilize government support of basic scientific research because he believed commercial firms lacked the incentives, capital, scale, and coordination necessary to make strategic scientific breakthroughs on their own. Bush’s vision proved correct, but the research landscape has evolved enormously since.

More From Our Experts

The American innovation ecosystem still rests on the foundation of basic research conducted in government supported labs and universities, but in several sectors—computing, space-based systems, and biotechnology, to name a few—the private sector, by virtue of its immense human and financial capital, owns the cutting edge. Just look at the numbers. In the mid-1960s, the federal government funded nearly 70 percent of all R&D conducted in the United States. By the 2020s, the private sector funded some 70 percent of it. Federally backed R&D accounts for some 0.7 percent of the U.S. GDP, down from its 1964 peak of 1.9 percent.

But not all research dollars are created equal. Private sector R&D is by definition a profit-driven enterprise bound to focus on commercial applications with relatively near-term revenue potential. The national interest, however, does not always align with commercial interests. Defunding basic research runs a real risk that the United States could fail to produce valuable but not yet commercially viable breakthroughs—or, indeed, the breakthroughs necessary for subsequent commercial successes.

More on:

Technology and Innovation

That the private sector owns the cutting edge also poses a daunting governance challenge: how can the government regulate powerful new technologies that it doesn’t control, hasn’t adopted, and in many cases doesn’t understand?

These questions, and the growing need to align the U.S. innovation ecosystem and the national interest, drove Stanford University to create the Stanford Emerging Technology Review (SETR), a joint venture between the policy wonks at the Hoover Institution and the world-renowned researchers at Stanford’s Engineering School, Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, and other departments and centers spanning the spectrum of natural sciences. SETR provides policymakers with accessible and deeply researched summaries of the state of the art across ten key emerging technologies, while highlighting policies that could preserve and advance America’s technological edge.

As SETR’s 2025 report outlines, while artificial intelligence has gotten the biggest headlines, it’s hardly the only game in town. Biotechnology and synthetic biology, cryptography, lasers, materials science, neuroscience, robotics, semiconductors, space, and sustainable energy technologies will all determine America’s future national power. Some of the most promising developments are at the nexus of two or more of these technologies.

Biotechnology is a perfect example. Advances in computing and chemistry have opened up new possibilities for biomanufacturing and synthetic biology, changing the way we produce everything from medicines to fuels to chemicals. Scientists are even beginning to leverage DNA as an efficient medium of data storage and computation. By McKinsey’s estimate, these combined advances in biotechnology, which sprang largely from research in U.S. labs backed by government funding, could generate some $2 to $4 trillion in annual economic gains within the next two decades.

But we’re not guaranteed to capture this opportunity. Sustained public investment in foundational bioengineering research is required. If the public sector retreats, the United States might well face a “Sputnik moment” in biotechnology. SETR found that China is laser-focused on this domain, lavishing its labs and companies with billions of dollars in research grants and tax credits. It should come as little surprise, then, that China churned out nearly nine times the number of highly cited synthetic biology papers than the United States did in 2023. And China isn’t just making paper gains: last year, researchers in China produced the first-ever synthetic plant chromosome.

The Chinese government’s spending on basic research more generally is growing at six times the rate of the U.S. government’s. There would be serious costs to yielding our technology leadership to China and having to compete in a world where China sets the rules.

Enter President Donald Trump. Whether it’s artificial intelligence, robotics, space-based systems, or nuclear reactors, he wants the United States to win. He believes that deregulation is the answer, and that his administration has been “given a mandate by the American people to streamline our bloated bureaucracy.” Deregulation is one thing, and in certain industries, cutting red tape may lead to greater and more effective technological experimentation. But now is not the time to starve support for basic research—one form of investment that made America great in the first place.

Trump’s basic instincts are correct: he can and should leverage his immense political capital to usher in a new golden age of American innovation. To do so, though, he should spurn slash-and-burn cuts to federal research funding and embrace his own family’s distinguished history of American innovation. As he has often noted, his uncle taught at MIT for more than forty years. “Dr. John Trump. A genius. It’s in my blood.” Indeed, that very uncle got his big break when he went to work for Vannevar Bush’s nascent government agency, the National Defense Research Committee. He went on to make key advancements in radar technology that helped the allies win World War II.

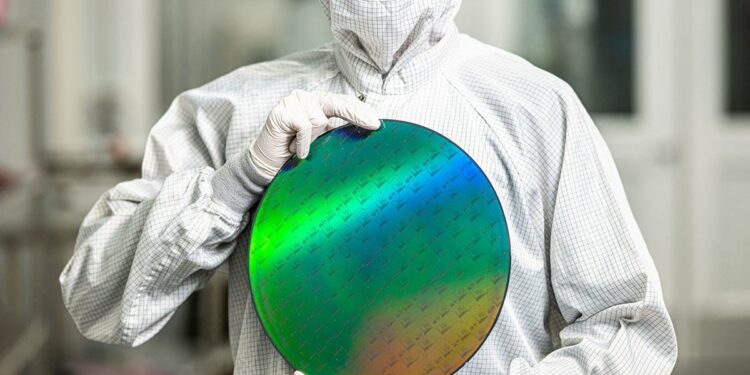

To explore the impact of emerging technologies and the future of U.S. science and technology policy, CFR, in partnership with our friends at SETR, has just launched a new podcast series, The Interconnect. As its name suggests, The Interconnect is designed to bridge the divide between technologists in Silicon Valley, policymakers in Washington, and business leaders around the world, all in an effort to advance American competitiveness. The podcast kicked off earlier this month with an episode on chips and the future of computing, with Stanford’s Martin Giles as its host. Give it a listen and let us know what emerging technology and policy issues you’d like to see CFR dive into next.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=67c29d79bab1409eb804aa3d537b1e1d&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cfr.org%2Farticle%2Fnew-golden-age-american-innovation&c=13337500086029409125&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2025-02-28 05:57:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.