The phrase ‘moves in twos’ has been around for a long time in coaching circles, and anyone who has experienced training exercises around that theme would know that Lionel Messi is your perfect partner.

Both of Argentina’s goals in their Copa America opening victory against Canada came down to the relationship between Messi and a team-mate — their movement, his pass — and also served as a reminder that the simplicity of a diagonal ball and a straight run, or a straight ball and a diagonal run, is often a winning formula.

Argentina are superb at those interactions in pairs, which can turn 11-a-side football into two-player games through uncomplicated but hugely effective ways of outwitting opponents.

For those of you who are interested in coaching, Dan Wright, Brighton’s academy coaching and pathway manager, puts on an excellent session on The Coaches’ Voice on this subject, showing academy players how they can make use of a variety of methods to succeed in a two-versus-two scenario — and only one of them involves taking on an opponent.

Both of those passing combinations mentioned above feature, as well as underlaps and overlaps, and an old Messi favourite that delivered two goals in Argentina’s final pre-Copa America warm-up game against Guatemala: the one-two to eliminate.

That kind of craft and guile to open up a defence seems so ingrained in Argentina’s footballing culture, where the mixture of skill, wit and imagination in their attacking play makes them such difficult opponents to contain. One wrong step and they’ve punished you. Just like they did with Canada.

In a way, the lead-up to Argentina’s second goal against Canada was totally out of sync with how Thursday’s game in Atlanta was played.

Canada operated a disciplined mid-block for much of the evening, initially in a compact 4-2-4 shape and later in a 4-3-3, putting the onus on Argentina to come on to them. But with time running out and Argentina almost provocatively going all the way back to goalkeeper Emiliano Martinez after initially being on the attack, Canada changed tact and pressed high and aggressively. In doing so, they played into Argentina’s hands.

Cristian Romero’s cross-field pass to Nicolas Otamendi was slightly loose and gave Canada’s Jacob Shaffelburg even more encouragement to chase hard, leaving Lisandro Martinez free in the process. It was a gamble that didn’t pay off for that reason. Otamendi lifted the ball over Shaffelburg’s head to Martinez and, with the Canada substitute now out of the game, Argentina had a three-versus-two overload on their left. A couple of one-touch passes from Martinez and Giovani lo Celso, the first via the head and the second on the volley, ensured that Argentina took full advantage.

As Marcos Acuna travelled over the halfway line with the ball and passed inside to Lo Celso, everyone was running forward for Argentina. Everyone apart from Messi, that is.

Messi was walking. Walking like a man who knew there was no chance the plane would depart without him.

He watched the panicked defenders retreat — Richie Laryea sprinted past him on his outside, prompting Messi to briefly glance to his right to weigh everything up — and by the time he received the ball from Lo Celso, the centre of the pitch midway inside the Canada half had emptied.

That area — a huge area — belonged to Messi.

Essentially, there had been no space for Messi to run into, but plenty of space that others were going to leave behind for him. In that sense it feels like a lesson in the art of standing still to receive the ball or, in Messi’s case, barely putting one foot in front of the other.

“He’s not running, but he’s always watching what happens,” Pep Guardiola said in the 2019 documentary, This Is Football. “He smells the weak points in the back four. After five, 10 minutes, he has a map in his eyes, in his brain, to know exactly where is the space and what is the panorama.”

If that’s the case, Messi might have been wearing a blindfold in the 88th minute against Canada. Either way, it was clear Canada were in trouble from the moment he had possession. A man who requires little time or space to pick a pass had plenty of both.

Lautaro Martinez made it even easier for him by making an excellent diagonal run across Moise Bombito and behind Derek Cornelius, who were drawn to the ball and preoccupied with Messi — there’s the four participants in your two-versus-two mini-game — and the Inter Milan striker converted.

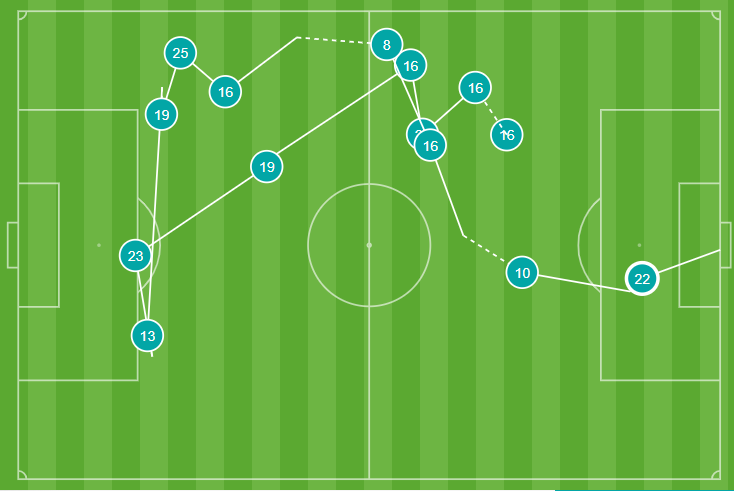

There were 12 Argentina passes in total in a move that went from front to back and, to quote Lionel Richie, Back to Front, and eight different players featured (as shown in the image below). But it was the devastating connection between two of them at the end that did the damage.

Argentina’s first goal was remarkably similar, albeit the run was straighter and the pass slightly angled. Once again Messi was the architect, this time after Stephen Eustaquio found himself outnumbered on a throw-in and, crucially, jumped forward to engage with Rodrigo De Paul, leaving Messi free. Eustaquio didn’t move much but he moved enough, and the same was true of Messi in order to receive and turn.

It was as if a switch flicked in Alexis Mac Allister’s brain at that point — he started his run in behind Bombito before Messi shaped to play the pass (Messi had almost certainly already thought about playing it), safe in the knowledge that the ball would come. Messi’s delivery was inch-perfect and although Mac Allister took a whack from the Canada goalkeeper Maxime Crepeau, he managed to prod the ball into the direction of Julian Alvarez a split-second before.

That mutual understanding between Argentina players is such an enjoyable feature of their play.

Six days earlier, Messi combined beautifully with Enzo Fernandez to set up a goal for Lautaro Martinez against Guatemala, this time via a one-two that took an entire defence out of the game and which worked so effectively because the Argentina captain ran in a totally different direction (forward) to where he was passing (sideways).

There is an obvious progression to all of this in matches and also in the ‘moves in twos’ training mentioned earlier.

Introduce another player, who can only move laterally, to bounce balls off before scoring and you have everything in place to encourage the kind of clever third-man run that led to Argentina’s final goal in their 3-0 victory over El Salvador in March (illustrated below).

Like a snooker or a billiard player thinking two shots ahead, Lo Celso is already on the move before Leandro Paredes has played a pass into the feet of Martinez, with the Tottenham Hotspur midfielder anticipating (or maybe that should be dictating) what will happen next. Martinez duly nudges the ball into Lo Celso’s path and Argentina have scored.

Argentina are not reinventing the wheel with any of these moves, but as Johan Cruyff once said: “Playing football is very simple. Playing simple football is the hardest thing there is.”

(Top photo: Hector Vivas/Getty Images)

Source link : https://www.nytimes.com/athletic/5583727/2024/06/24/lionel-messi-argentina-copa-america-canada-analysis/

Author :

Publish date : 2024-06-24 00:22:52

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.