ASPEN • For the seasonal, rotating menu at Mawa’s Kitchen, beets were a curious choice.

Beets recall the childhood home of the chef and owner, Mawa McQueen, who is quick to banish whatever glitzy picture of Paris people have in mind when she tells them she grew up there.

For her, her mom and other kids who emigrated from Africa, “it was the ghetto,” McQueen says. “Or call it low-income housing if you want to be polite.”

It was a two-bedroom apartment for 12 people, she recalls. And for whatever meal McQueen could scrape together for siblings and half-siblings while her mother and stepfather were away working, it often included beets.

“In France, we always ate beets. I hate beets,” McQueen says. “The only way I eat beets is if it doesn’t taste like beets.”

Roasted Beets with whipped feta, toasted pistachio, fine herbs and madras curry vinaigette at Mawa’s Kitchen in Aspen, Colo., Wednesday, June 19, 2024. (The Gazette, Christian Murdock)

Christian Murdock, The Gazette

This summer’s beets at Mawa’s Kitchen have been roasted and disguised by whipped feta, toasted pistachios, herbs and an Indian curry vinaigrette — just one sample of innovative, globe-trotting dishes here recognized by the highest honors of the culinary world.

McQueen grew up in a neighborhood of immigrants, where flavors spanned the continents. She honors those neighbors at Mawa’s Kitchen.

The peanut stew is straight from her native West Africa, as is the lamb tagine. Jerk salmon and chicken recall the Caribbean, while shrimp skewers are coated in a Middle Eastern spice. Oxtail, commonly associated with Jamaica, is prepared in the French bourguignon style. Other fusions have trended Latin and Mediterranean.

Berbere grilled shrimp, pineapple shrimp skewer with madras curry sauce, at Mawa’s Kitchen in Aspen, Colo., Wednesday, June 19, 2024. (The Gazette, Christian Murdock)

Christian Murdock, The Gazette

A recent appetizer featured mango, burrata and toasted hazelnut — symbolizing the simple, healthy, nutrient-rich tenets of McQueen’s cooking. The board added exotic spices and a curious, green spread. “I have to Africanize it,” she says.

The beets, meanwhile, symbolize the unlikely story of the woman in the kitchen — those once-despised root vegetables turned delicious.

McQueen’s story is one of astonishing transformation. It’s a story that begins in a cramped African abode and weaves around to Colorado’s high cuisine kingdom of Aspen, where that little girl once without shoes, a bed, a toilet or much of anything else is now known as The Queen.

Twenty years after she arrived in America, the James Beard Foundation nominated McQueen for Best Chef of the West in 2022. A year later, Colorado’s inaugural Michelin Guide included Mawa’s Kitchen.

Onlookers see a rags-to-riches tale. But McQueen thinks of herself as the underdog still, pointing to lingering factors that almost sank her business before the James Beard call.

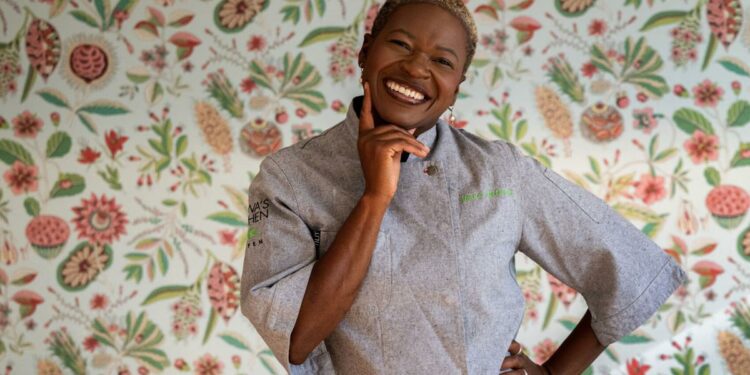

“This is Aspen still. It’s still the seasonality,” says McQueen, who always has gotten by with a megawatt smile, quick wit and a no-excuses attitude as straight as her talk. “And I still have the (worst) location.”

Mawa’s Kitchen remains somewhat hard to find. It’s away from Aspen’s walkable, bougie core, on the outskirts in a business center across from the airport. The restaurant remains where it started in 2014, tucked behind a gas station, amid mechanics, plumbers, other handy shops and nondescript offices.

The entrance to Mawa’s Kitchen in Aspen, Colo., Wednesday, June 19, 2024. (The Gazette, Christian Murdock)

Christian Murdock, The Gazette

To pay bills, McQueen once cleaned an office next door. Now she owns the space for her expanded restaurant — indeed another rags-to-riches hint, to go with the crepe stand she owns in town along with a granola company.

But no, McQueen says: “I’m still trying to make it. I haven’t made it yet. I haven’t scratched the surface of what I’m supposed to be.”

Call it unstoppable ambition. That’s the name of her book, which is equal parts memoir and self-help.

Importantly, “Unstoppable Ambition” is printed in French. McQueen has since returned to her former homeland to promote the book and send a message to impoverished youth — to the kids like her in that Parisian ghetto.

“I said to them, ‘Who created the American dream? Immigrants created the American dream.’”

This is the dream McQueen went on to dream coming out of Africa’s Ivory Coast. There, she thought of herself as a “bastard child,” she says.

She was born in 1974 to a Christian mother and a Muslim father. The man was absent much of her first 10 years.

“While I look like my mom, I have a name that is all my father: Mawa,” she writes in her book. “Growing up, that name made me an outsider. And I hated my name so much.”

She was made to believe her name — and the religion it represented — were ugly. At 9, when she was bussed to live with her father, she was terrified.

She found life with his tribe to be much more comfortable.

“Suddenly, I ate three meals a day,” reads her book. “I had clothes, a proper bed (which I shared with my grandmother and namesake), a community that claimed me …”

Just as suddenly, it was all taken away.

McQueen’s mother moved her to Paris, to live with siblings and half-siblings of another man. They would live outside the city, around the commune of Trappes.

“Like you could get trapped there,” McQueen says. “Back in the day, it was very dangerous.”

Her book recounts her anger. Anger at her mother for leaving her to cook and tend to the kids, for taking her away from her father. Anger at the man for him not reaching out.

Later, when she was 23, McQueen recounts journeying back to his deathbed. At the sight of her, she recounts tears filling the man’s eyes.

She continues in the book: “That was the first crack in the wall of victimhood and anger I had built around myself. … Without that wall of blame, I could see so much more clearly. I wasn’t unloved or being punished. Instead, there were factors I had never been able to see — aspects of our culture, generational trauma and so much more — that had shaped my life.”

McQueen was wiser by then. In Trappes, she gained inspiration for what not to be, and from influential outsiders she gained something else; she credits a school headmaster, seeing her potential, for guiding her to culinary school.

There she encountered another invisible factor that threatened to shape her. Racism sought to keep her out of white, male-dominated kitchens.

“When I got out (of culinary school), nothing. Nobody would hire me,” she says. “They’re like, ‘Yes, you can do the dishes.’”

McQueen turned to work as an au pair in London, tending to the children and home of a white woman. The woman loved “The Oprah Winfrey Show.”

“I saw a white woman being fascinated by a fat Black woman on TV,” McQueen says. “This is how my brain processed it … like, nobody’s fascinated by us!”

Who is that? she asked her boss. “And she said, ‘It’s one of the most powerful women in America.’ … That was it for me. I was going to America.”

Mawa’s Kitchen owner and chef Mawa McQueen works in the kitchen of her Aspen, Colo., restaurant Wednesday, June 19, 2024. (The Gazette, Christian Murdock)

Christian Murdock, The Gazette

She would go on a green card in 2002, landing a summer job at White Barn Inn in Kennebunkport, Maine. During winters, she waited tables at The Little Nell in Aspen.

One Christmas, a regular asked McQueen to serve at her house party. That sprung a catering business; McQueen grew a list of customers across mansions and private jets. The success sprung a full-service restaurant.

But soon, Mawa’s Kitchen seemed doomed.

“It was hell,” McQueen says.

In the out-of-sight business center, tables sat empty. McQueen kept doing more — more meals, a bar, a separate and ill-fated business venture, cleaning the office next door — only to find shrinking profits and climbing debts.

McQueen and her husband tried cutting costs and working more to seemingly no avail. “It was painful, painful, painful,” she says.

The couple crafted an exit strategy. “And then I get the call,” McQueen says.

The call informing her of the James Beard nomination.

“I run to my husband,” McQueen says. “I’m like, ‘Honey, the white boys think I’m good!’”

She laughs while recognizing the serious matter of such honors often passing women like her.

Mawa’s Kitchen and her Crepe Shack are the only Black-owned eateries in Aspen. The reputation is complicated for McQueen, as are the awards that have highlighted her representation in town.

“I don’t want to be known as the only Black place in Aspen. I want to be known as a great chef,” she says. “Just like I don’t want to be given an award because I’m Black. I want an award because I deserve it, and I worked my butt off.”

But yes, she has brought culture to Aspen, and for that she is proud. That was, after all, the big idea with Mawa’s Kitchen.

“I was like, ‘Aspen needs culture!’” McQueen says. “These kids think everybody should eat caviar and steak and sushi.”

Try the beets, she might suggest.

Not just any beets, but her beets — the past meeting a sweet, savory present.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66d8557ee1694812a23bef0988e8764d&url=https%3A%2F%2Fgazette.com%2Ffood%2Ffrom-africa-to-aspen-chef-mawas-amazing-rise-to-stardom-in-colorado%2Farticle_ea861e60-387d-11ef-8e57-07ed697bf6fa.html&c=12198978874325918252&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-09-03 13:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.