Professor Wilfred Codrington III expands on this:

“The populations in the North and South were approximately equal, but roughly one-third of those living in the South were held in bondage. Because of its considerable, nonvoting slave population, that region would have less clout under a popular-vote system… With about 93 percent of the country’s slaves toiling in just five southern states, that region was the undoubted beneficiary of the compromise.”

Hence how the Founding Fathers came to codify the enslaved population at three-fifths the representative value of the free population. The three-fifths compromise basically enabled slave owner Thomas Jefferson to defeat northern abolitionist John Adams for the presidency in 1800. (Source: “Electoral College is ‘vestige’ of slavery, say some Constitutional scholars,” PBS NewsHour) Following the Civil War between the abolitionist Northern states and the slave-holding Southern states, it was through the 14th Amendment of 1868 that the three-fifths compromise was finally redacted.

As Professor Jelani Cobb notes in One Person, One Vote?, “[M]illions of people who are not given status as citizens but who are nonetheless counted for representation is, at best, a contradiction for a country that owes its origins to the idea of democracy.”

Columbia Journalism School Dean Jelani Cobb, from the film One Person, One Vote?

Electoral Voters, Not So Anonymous

While in most election years Americans typically pay little attention to who Electoral College voters actually are, with contentious recent elections making the voting process front and center, their identities have increasingly become of keen interest. Did you know you can now go onto Wikipedia and find a list of all 538 electors for the 2016 election, and for 2020 as well? Or Politico will just post the whole list, as they did in 2016.

Some electors are prominent enough, often elected or formerly elected (nonfederal) officials themselves or similar, that they have their own Wikipedia page. One woman elector in New Jersey is listed as the first Bangladeshi-American female to hold elected office in the United States. New York state had some prominent elector names, including former President Bill Clinton, former New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, and New York Attorney General Letitia James PBS.

And one of North Dakota’s three electoral voters, Duane Mutch, was 91 years old when he cast his electoral vote for Donald Trump in 2016. (He passed away before serving as an elector in the 2020 election.)

Faithless Electors

In the rare but controversial occasion that electors do not cast their vote in accordance with their state’s popular vote results, they earn the prickly designation of “faithless electors.”

Faithless electors have been a feature of the Electoral College since the first recorded instance of Samuel Miles in 1796 in Pennsylvania, who was pledged to vote for John Adams but cast his vote for Thomas Jefferson instead.

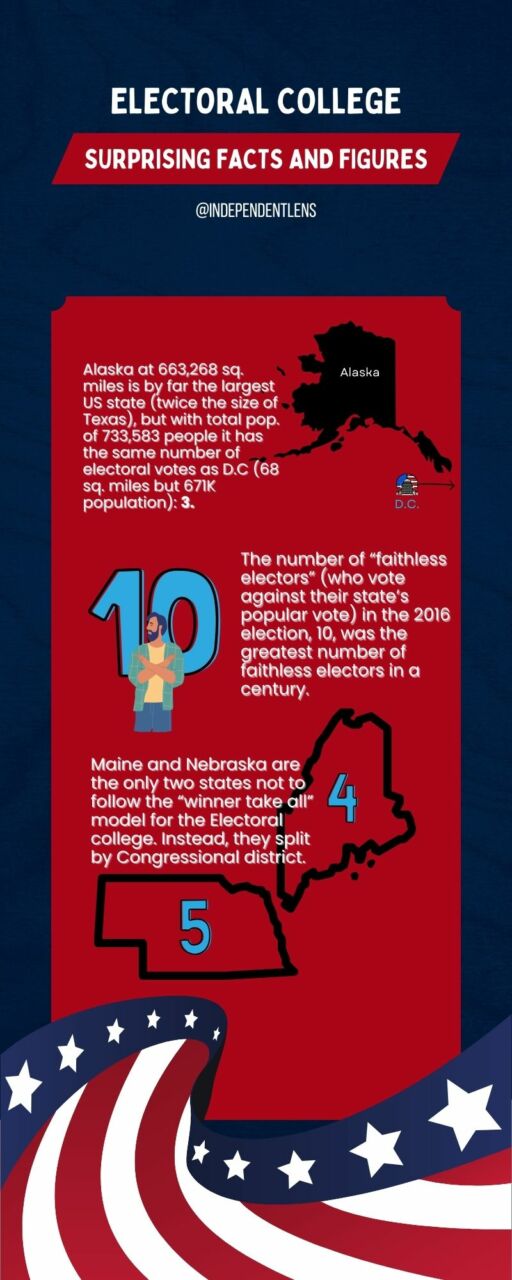

The most glaring, recent example took place in the 2016 race between Hillary Clinton (D) and Donald Trump (R), where ten electors from both major parties deflected their votes in an (ultimately unsuccessful) attempt to sway election results, the greatest number of faithless electors in a century.

PBS NewsHour, 2020:

This faithless elector chaos made its way up to the Supreme Court in not one but two cases in 2020. NPR correspondent Miles Parks reported that Michael Baca—a Republican elector from Colorado who did not cast his vote for popular vote winner Trump—”violated a state law that required electors to vote the way the people do.”

The Supreme Court concluded in Baca’s case, as well as in the case of Bret Chiafalo in Washington, that states “were within their rights to punish or switch out faithless electors.” With concern amongst some legal experts about government power balances around state law versus federal law, the debate rages on.

No, Not Anyone Can Be an Elector

The Constitution lays out a clear framework for determining Congressional and electoral representation. Each state’s number of Congressional seats translates to their number of Electoral College votes. From this pool of 538, a candidate needs a simple 270 majority to win. When it comes to how electors are chosen, however, the parameters vary.

There are two federally mandated criteria for elector service that were intended as checks and balances against political conflicts of interest. The first of these, enshrined in the original Constitution, bars past and present Congressional members and current federal officials from serving as electors (so a past president like Bill Clinton was eligible to be an elector, but it would’ve been awkward if this was while he was serving as president).

The second—codified in the 14th Amendment that legally abolished slavery following the Civil War—stipulates that anyone who has participated in insurrectionary or foreign enemy activity against the United States also cannot be an elector. [Project on Government Oversight (POGO), a non-partisan organization: “The Constitution’s Disqualification Clause Can Be Enforced Today.”]

Individual states, and the political parties within them, are otherwise afforded the right to appoint electors and set eligibility requirements for their service as they see fit. While there is technically no federal requirement for electors to cast their party’s vote based on the state’s popular vote winner, many states operate under this assumption of party allegiance—and even legally require their electors to abide by it.

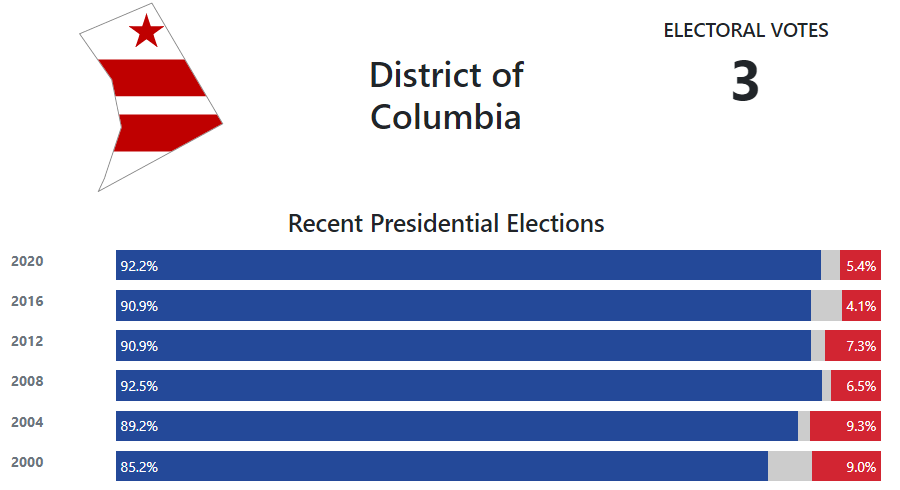

Washington D.C.: 3 Electoral Votes, 1 Act of Civil Disobedience

The District of Columbia’s population of over 700,000 residents gives it more people than the states of Vermont and Wyoming. Even though the American capital city only has one delegate in the U.S. House and no U.S. senators, D.C. is the only non-state enfranchised for presidential elections, gaining three electoral votes through the 23rd Amendment in 1961. In the heavily Democratic-leaning city (roughly 9 to 1 in favor of Democratic presidential candidates year-to-year), no Republican has ever won an electoral vote.

From 270toWin, a non-partisan election tracking site

From 270toWin, a non-partisan election tracking site

The one unusual moment in recent D.C. electoral history was in 2000 (the incredibly close year that came down to Florida’s hanging chads recount) when elector Barbara Lett-Simmons, an education administrator, pledged for Democrats Al Gore and Joe Lieberman but cast no electoral votes as a protest of D.C.’s lack of voting congressional representation. Lett called it an act of “civil disobedience,” not a faithless elector.

The Outlier States: Maine and Nebraska, the Congressional District Model

The states with the most electoral votes are the battlegrounds upon which presidential candidacies are fought. These battleground states are also prized for the tight victory margins between parties from election cycle to election cycle, hence their nickname: “swing states.” Just as not all states are equal in terms of electoral numbers, not all states calculate them in the same way.

Most states follow the “winner take all” model, whereby whichever candidate wins the state’s popular vote wins all of that state’s electoral votes. But two states notably deviate from this: Maine and Nebraska. They follow the Congressional District model, whereby whichever candidate wins the popular vote within each of a state’s congressional districts appoints an individual elector, plus two “at-large” electors based on which candidate wins the state’s popular vote.

Maine has two congressional districts while Nebraska has three, giving the former four electoral votes and the latter five.

Some background first: Maine joined the Union in 1820 through the Missouri Compromise signed by then-President and Founding Father James Monroe, granting them Union entry as a free state on the condition that Missouri joined as a slave state, in a sort of 1-for-1 “trade.” Maine became the first state to adopt the Congressional District elector model in 1972 through the efforts of Rep. John Martin (D); his proposed change took effect in 1976.

Nebraska became a state in 1867 during Andrew Johnson’s presidency, shortly after the Civil War that brought tensions between free and slave states to a head (Johnson had served as Abraham Lincoln’s vice president until the latter’s assassination). In 1992, Nebraska became the second state to adopt the Congressional District elector model.

In the 2020 presidential election, Donald Trump won four of Nebraska’s electoral votes by winning the popular vote and the 1st and 3rd Congressional Districts. Joe Biden won one vote from the 2nd Congressional District containing Omaha, at left, splitting the state’s electoral vote for the second time in history. [Via Wikimedia Commons]

In the 2020 presidential election, Donald Trump won four of Nebraska’s electoral votes by winning the popular vote and the 1st and 3rd Congressional Districts. Joe Biden won one vote from the 2nd Congressional District containing Omaha, at left, splitting the state’s electoral vote for the second time in history. [Via Wikimedia Commons]

Much remains at stake for these states’ electoral processes. Both have seen their electoral votes split twice: Maine in 2016 (Donald Trump’s 1 to Hillary Clinton’s 3) and again in 2020 (Trump’s 1 to Joe Biden’s 3); and Nebraska in 2008 (Barack Obama’s 1 to John McCain’s 4) and 2020 (Biden’s 1 to Trump’s 4).

Maine has become the latest state to join the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact—potentially making the 2024 presidential race their last as Electoral College participants.

Nebraska has also faced recent challenges from the legal team of candidate Donald Trump in an effort to return the state to a “winner take all” model.

Bianca Beyrouti (she/they) is an emerging writer born, bred, and based in the San Francisco Bay Area. She is also a seasoned independent filmmaker, whose work you can learn more about and follow at biancabeyrouti.com.

Sources and Further Reading

Faithless Electors:

Fair Vote: Faithless Electors

“Electoral College: In 1796, Samuel Miles Became The 1st Faithless Elector” (NPR)

“2020 Supreme Court decision offers ‘dangerous’ path for stealing election, legal scholars say” and “States can penalize wayward presidential electors, Supreme Court rules” (ABA Journal)

“Faithless Electors and Trump’s Final Futile Fight” (SCOTUS Blog)

History and Racist Origins

Fair Vote: “John Martin: Examining the history of electoral votes“

More from Jelani Cobb: “What Black History Should Already Have Taught Us About the Fragility of American Democracy” (The New Yorker)

Eligibility

Project on Government Oversight (POGO), a non-partisan organization: The Constitution’s Disqualification Clause Can Be Enforced Today

Nebraska and Maine

“Nebraska’s Vote Change” (Washington Post, 1991)

“Nebraska and Maine split their electoral vote. Is it a better system than winner-take-all?” (Nebraska Public Media)

“Maine House advances bill to join other states in scrapping the Electoral College” (Spectrum News)

“Nebraska push on winner-take-all electoral votes takes another hit in Legislature” (NBC News)

National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC)

For those process-lovers, PBS NewsHour covered Pennsylvania electors in the actual casting of votes for the 2020 election:

Related Films

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66ee5544d80e47f9807cdcc032b3becb&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.pbs.org%2Findependentlens%2Fblog%2Famericas-electoral-college-six-surprising-facts-about-the-who-and-how%2F&c=8017202984747017411&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-09-20 09:39:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.