A new genetic analysis of ivory artifacts from across Europe suggests that early Norse hunters ventured far into North American waters and likely interacted with indigenous North Americans as early as 985 CE, or over 500 years before Christopher Columbus’ “discovery” of the Americas.

The scientists behind the potential historical discovery’s genetic and isotopic analysis show that the ivory was harvested from the tusks of Walruses that lived in the North Atlantic waters off of present-day Canada. Their study also found that the long distances and extreme weather that Norse hunters would have endured to procure these tusks made it possible for them to interact and even trade with the indigenous people in the area.

“Walrus ivory was a prized commodity in medieval Europe and was supplied by Norse intermediaries who expanded across the North Atlantic, establishing settlements in Iceland and Greenland,” the study authors write. “However, the precise sources of the traded ivory have long remained unclear, raising important questions about the sustainability of commercial walrus harvesting, the extent to which Greenland Norse were able to continue mounting their own long-range hunting expeditions, and the degree to which they relied on trading ivory with the various Arctic Indigenous peoples that they were starting to encounter.”

The Bear Trap (88) and surrounding seascape. This is interpreted as a Greenland Norse storage facility located on the northwestern tip of the Nussuaq Peninsula. This location offered a sheltered harbor and proximity to the outer coast and the open sea, thereby reducing the danger of katabatic winds and becoming trapped by pack ice; the surrounding area also offers ready access to walrus haul-out sites and their shallow feeding grounds. Photo: Matthew Walsh

Potential Interactions between Greenland Norse and Indigenous North Americans

Due to the increasing demand for ivory, early Norse hunters occupied southwestern Greenland as early as 985 CE. These “Greenland Norse” were equipped with sufficiently advanced maritime technology to exploit the fertile walrus hunting ground.

While these hunters were settling in Greenland, the east coast of the North American continent and present-day Canada was already home to the Tuniit people. Anthropologists classify this population as a ‘Late Dorset Pre-Inuit’ population. These early Indigenous North Americans were ultimately replaced by the Thule Inuit, who arrived from the continent’s West coast sometime in the 13th century.

By Dylan Kereluk from White Rock, Canada – Flickr, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=351717

By Dylan Kereluk from White Rock, Canada – Flickr, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=351717

Although there are some famous examples of potential early Norse settlements in North America that predate Columbus, such as the 11th-century L’Anse aux Meadows National Historic site in Newfoundland, there was no definitive evidence predating this study that these 10th-century Norsemen expanded their hunting grounds across the Atlantic. Furthermore, there was no prior evidence that the two groups interacted or traded before medieval times.

“Key historical questions about the Greenland Norse (ca. 985 to 1450 CE) revolve around the nature and extent of Norse encounters with the Tuniit and Thule Inuit, whether organized trade in walrus ivory emerged between groups, and if so, where, when, and why such interactions occurred,” the authors explain.

Genetic Evidence European Ivory Came from North American Waters

To look for scientific clues that these Norse hunters may have ventured far west and potentially encountered these early Americans, Emily Johana Ruiz Puerta from the University of Copenhagen and colleagues looked for ivory artifacts made during that period. Specifically, they wanted ivory harvested from Walrus tusks brought to mainland Europe by the Greenland Norse between 850 and 1350 CE. The researchers say this period is when walrus tusk ivory “was exchanged into European trade and production centers via Norse intermediaries who operated across the North Atlantic.”

The research team extracted ancient DNA from museum collections (Emily Ruiz-Puerta sampling at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa) Credit: Emily Ruiz-Puerta

The research team extracted ancient DNA from museum collections (Emily Ruiz-Puerta sampling at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa) Credit: Emily Ruiz-Puerta

After collecting the artifacts that fit the location and time period, the researchers studied the genetic code of the animals from which the ivory was harvested. That data was compared against a database of walrus DNA collected from animals known to have inhabited the area between 950 and 1,500 CE.

“We use high-resolution genomic sourcing methods to track walrus artifacts back to specific hunting grounds,” the authors write. That data also revealed a discernable pattern hunting pattern that showed the Greenland Norse expanding their hunting grounds as they methodically depleted the walrus stocks in their local waters.

“During the “Early Period” prior to 1120 CE, harvested walruses primarily came from stocks far removed from known settlement areas of the Tuniit and Thule Inuit peoples,” the press release announcing the findings explains. With limited evidence for contact with these two main Indigenous groups who occupied the northern Davis Strait, the researchers concluded that direct Norse-Indigenous trade was unlikely at this time.”

However, the researchers also found that the tusks harvested after 1120 CE showed a shift in origin back toward the waters off of North America. Half of the artifacts tested were associated with walrus populations living in the North Water Polynya in the Davis Strait far north and west of Greenland.

According to the authors, this evidence suggests that Greenland Norse hunters “substantially expanded their range as far north as the Pikialasorsuaq in the “Late Period” after 1120 CE.”

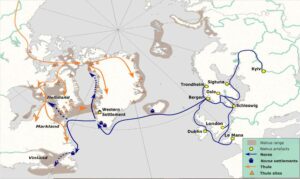

Fig. 6. Early circumpolar globalization: schematic reconstruction of the Arctic Ivory Road. Shifting walrus exploitation patterns suggest a “domino” model: the Norse systematically depleted more accessible walrus stocks to supply the booming European ivory trade; the search for fresh sources of ivory was one factor driving Norse expansion into the Northwest Atlantic, including initial colonization of Iceland, and the establishment of Norse settlements in Southwest Greenland. Exploration of coastal North America (Helluland, Markland, and Vinland) by the Norse likely resulted in initial full-circle encounters with various Indigenous North American groups across a broad “contact” frontier running from the Canadian Maritimes up to the High Arctic. Credit: Ruiz-Puerta et al., Sci. Adv. 10, eadq4127 (2024)

Fig. 6. Early circumpolar globalization: schematic reconstruction of the Arctic Ivory Road. Shifting walrus exploitation patterns suggest a “domino” model: the Norse systematically depleted more accessible walrus stocks to supply the booming European ivory trade; the search for fresh sources of ivory was one factor driving Norse expansion into the Northwest Atlantic, including initial colonization of Iceland, and the establishment of Norse settlements in Southwest Greenland. Exploration of coastal North America (Helluland, Markland, and Vinland) by the Norse likely resulted in initial full-circle encounters with various Indigenous North American groups across a broad “contact” frontier running from the Canadian Maritimes up to the High Arctic. Credit: Ruiz-Puerta et al., Sci. Adv. 10, eadq4127 (2024)

Distance and Vessel Limitations Increase Odds of Trade with indigenous North Americans

Although the authors found that trade between the local indigenous North Americans and Greenland Norse was less likely before 1120 CE, they note that the two groups still probably knew about and even interacted with each other due to the duration they shared the same hunting grounds.

“The Greenland Norse were certainly aware of Thule Inuit and Tuniit groups and may have used initial encounters to explore opportunities for more formalized ivory exchange, though what the Norse could offer in return remains unclear,” they write. “Some Greenland Norse contact with the Tuniit does seem likely despite the scarcity and ambiguity of archaeological evidence, especially considering the 300 years of temporal overlap in the Baffin Bay and Davis Strait area.”

The team also tested the sailing technology available to the Greenland Norse to see how realistic it was for them to mount long-range hunting expeditions in North American waters. Those studies found a rapidly narrowing window for hunting during the ice-free season of their local territory the farther away they traveled from Greenland’s shores. In some cases, the actual time on the hunting site may have been as short as two weeks, dramatically limiting the amount of walrus tusks that could be harvested.

Experimental insights into Greenland Norse seafaring capabilities: example of a “smaller” vessel (with oars and sail). This is a Norwegian fyring during sea trials. Note the very limited space for cargo (Roskilde Fjord, Denmark, June 2023). Photo: Greer Jarrett

Experimental insights into Greenland Norse seafaring capabilities: example of a “smaller” vessel (with oars and sail). This is a Norwegian fyring during sea trials. Note the very limited space for cargo (Roskilde Fjord, Denmark, June 2023). Photo: Greer Jarrett Experimental insights into Greenland Norse seafaring capabilities: example of a larger expeditionary sailing vessel. This is a Norwegian fembøring, a direct descendant of the Norse clinker tradition used in Greenland (Vestfjord, northern Norway, May 2022). Only these larger sailing ships, owned and sponsored by richer farmers and elites, would have been capable of reaching the North Water Polynya during single-summer expeditions. Photo: Greer Jarrett

Experimental insights into Greenland Norse seafaring capabilities: example of a larger expeditionary sailing vessel. This is a Norwegian fembøring, a direct descendant of the Norse clinker tradition used in Greenland (Vestfjord, northern Norway, May 2022). Only these larger sailing ships, owned and sponsored by richer farmers and elites, would have been capable of reaching the North Water Polynya during single-summer expeditions. Photo: Greer Jarrett

The study also found that limitations to the boats used by these Norse hunters could have led them to consider trading with the locals. Specifically, the vessels most well-equipped for the long journey to North American waters and back during the roughly four-month window were potentially too limited in cargo capacity to justify such a long-range hunt.

“The small Greenland Norse communities may have struggled to mount long-range hunting expeditions, making trade with other Arctic hunting groups an attractive alternative,” they write.

The Earliest Phases of Circumpolar Globalization?

In the study’s conclusion, the researchers note that more archaeological evidence would be needed to definitively declare that Norse hunters from Greenland interacted with indigenous North Americans over 500 years before Columbus. However, they also point out that the genetic data tracking the origin of ivory tusks collected by those same hunters makes it increasingly likely they did interact with each other centuries before Columbus.

“These results substantially expand the assumed range of Greenland Norse ivory harvesting activities and support intriguing archaeological evidence for substantive interactions with Thule Inuit, plus possible encounters with Tuniit (Late Dorset Pre-Inuit),” they write.

The authors also note that if these interactions prove true, they could represent the earliest example of the two groups that left Africa nearly 70,000 years ago reconnecting with each other across the Atlantic Ocean millennia later.

“Whatever the precise character of these interactions, the Pikialasorsuaq (North Water Polynya) can now be identified as the most likely arena for the earliest phases of circumpolar globalization,” they conclude.

The study “Greenland Norse walrus exploitation deep into the Arctic” was published in Science Advances.

Christopher Plain is a Science Fiction and Fantasy novelist and Head Science Writer at The Debrief. Follow and connect with him on X, learn about his books at plainfiction.com, or email him directly at [email protected].

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66f6f8fa20554affbea6b6c750bbd0cd&url=https%3A%2F%2Fthedebrief.org%2Fshocking-new-evidence-suggests-norse-hunters-met-indigenous-north-americans-500-years-before-columbus%2F&c=5368254680172630663&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-09-27 07:14:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.