If Americans hear the names of Lee Harvey Oswald or John Wilkes Booth, they most likely would know their historical crimes. If the name John Hinckley comes up around anyone in Generation X or older, he or she would probably get the reference. However, if one pulls people aside on Any Street USA and asks them to name either of the would-be assassins of former President Donald Trump, it’s fair to wonder how many people would name either of them without knocking on Google’s door.

Whether it’s the cynicism and disinterest of the current electorate or the numbing speed of the modern news cycle, the limited shelf life of dual assassination attempts from the public’s daily discourse suggests an unprecedented disconnect between the major stories of the day and the people possibly affected by them.

Philip Seib, professor emeritus of journalism and public diplomacy at the University of Southern California, makes the simple analysis that the public forgets about killers who fail.

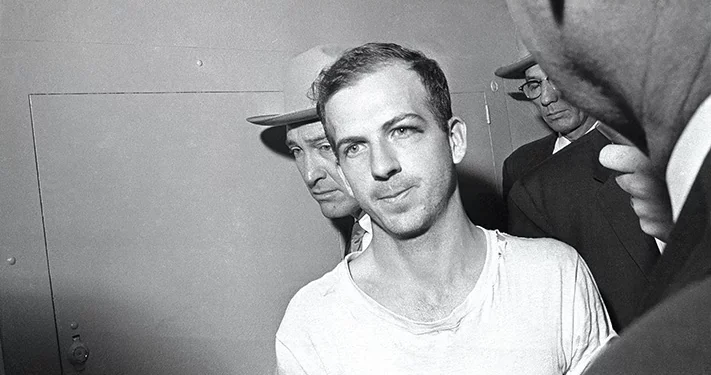

Lee Harvey Oswald is escorted by Dallas police for questioning after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963. (Getty Images)

“I think the assassins’ success or lack thereof might determine their lingering notoriety,” Seib said. “Booth and Oswald killed their targets and are better known than those who failed. Also, Lincoln is widely recognized as one of our greatest presidents, so Booth’s name remains known. Kennedy’s death was the first of its kind in the television era, so the audience for the immediate aftermath of the murder and for the funeral was national, global, and in real time.”

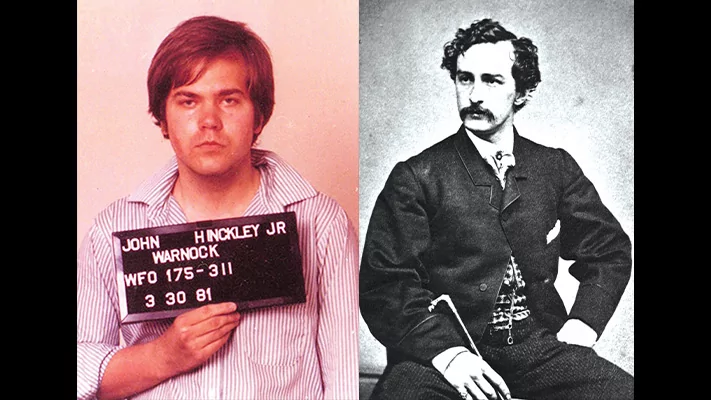

In the failed assassins department, Seib isn’t sure that Hinckley’s name would be recognized by many today.

“Also, who could identify the two women who tried to kill President [Gerald] Ford, even though one of them [Lynette ‘Squeaky’ Fromme] was already notorious because of her Manson family association?” he asked. “Citing the name Sara Jane Moore would probably elicit only blank stares.”

Shanto Iyengar, Stanford University’s William Robertson Coe professor of political science and of communication, acknowledged that the political landscape and rhetoric would’ve taken a severe course change had either Trump assassination attempt been successful, but he said he disagrees with Seib that the latest failed gunmen are already fading from public view because they couldn’t aim or failed to get a shot off near a golf course. Instead, he pointed to his thesis that the public is largely desensitized to violent events.

“What’s happened in the last couple of decades is that we’ve had a surplus of assassinations,” Iyengar said. “I’m not talking presidential assassinations, but we’ve seen people getting shot all the time — with mass shootings, in particular. That’s what makes the difference with people’s attention and memory.”

Left: John Hinckley Jr. attempted to assassinate President Ronald Reagan in 1981. Right: John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Abraham Lincoln in 1865. (Getty Images)

Left: John Hinckley Jr. attempted to assassinate President Ronald Reagan in 1981. Right: John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Abraham Lincoln in 1865. (Getty Images)

Iyengar reminds anyone trying to remember the names of Trump’s would-be killers that few people could remember the names of most mass shooters from the last several years.

“There have just been too many,” he explained. “People like Hinckley or Oswald stand out because of what they did was distinctive. Such actions are no longer distinctive because it seems like we have assassins everywhere now.”

The statistics bear Iyengar out, especially if one adds in the overall violent crime numbers in major cities. While there are disagreements on what precisely defines a mass shooting, the Department of Justice qualifies such an incident as firearm violence involving four or more victims. Over the last 10 years, the most deadly of such incidents included:

2022 Robb Elementary School massacre, Uvalde, Texas — 21 dead and 17 injured.

2019 El Paso Walmart attack — 22 dead and 26 injured.

2017 Las Vegas Strip concert massacre — 58 dead and 546 injured.

2017 Texas First Baptist Church shooting — 26 dead and 20 injured.

2016 Orlando nightclub attack — 49 dead and 58 injured.

In fact, among the top 20 deadliest mass shootings in American history, half took place over the last decade. Iyengar said he believes the frequency of such tragedies both dulls the public’s emotions and makes gun violence less newsworthy. Meanwhile, according to statistics from the DOJ and the Gun Violence Archive, the U.S. is on pace for between 400 and 500 mass shootings in 2024.

The professor used the automobile as opposed to the gun to demonstrate how the public interprets news. He argues deaths by car crash were more shocking in the 1940s and 1950s, when cars were still reasonably new to the overall American landscape. Today, a deadly crash wouldn’t generate anything more than an obituary in the local paper. Iyengar said he believes people have come to that shrug point with gun incidents — even when a presidential candidate is involved.

“A lot of this has to deal with span of attention,” Iyengar said. “In the 1980s and 1990s, attention spans were undoubtedly longer. To use the journalistic jargon, stories had legs. The story would last for multiple days because there wasn’t that much competition. News agencies would invest more in a given story because they were able to go with it for a longer period of time.”

Iyengar described a news environment in which the race for clicks is so fierce that agencies must always keep an eye on what rivals are doing while trying to find the next story that will keep their coverage ahead.

“As soon as something else comes up, the market incentive is to cover that instead,” he added. “As a result, even an assassination attempt is a top story for maybe 36 hours, and then something else replaces it because the news cycle is so accelerated.”

Iyengar adds alternative news sources to the mix, causing additional noise that smothers the public’s perception and memory. He said he believes people are no more or less interested in the world around them as they’ve ever been but that they have reduced opportunity and energy to examine it in much detail.

“From social media to other online source, there’s so much more going on outside what we called conventional news that people have less time to be more effective news consumers,” Iyengar said. “Interest in public affairs has always been low, and if you look at how much social media content deals with the traditional news cycle, it remains less than 10%. Whether it’s an assassination attempt or a local shooting, gun violence doesn’t draw much reaction anymore.”

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Back in Southern California, Seib admitted even he, too, already forgot the names of the men who targeted Trump, and he said he assumes they’ll be lost to history soon.

“Time is also a significant factor,” he said. “Assassins’ ‘fame’ fades over the years. Who remembers the names of the assassins who killed President Garfield and President McKinley? No one.”

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=6724a98144774b0e8898197b7336583d&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.washingtonexaminer.com%2Fpremium%2F3205673%2Fwho-remembers-assassins-forgetfulness-political-violence-perpetrators%2F&c=5724089803876885383&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-10-31 22:31:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.