Â

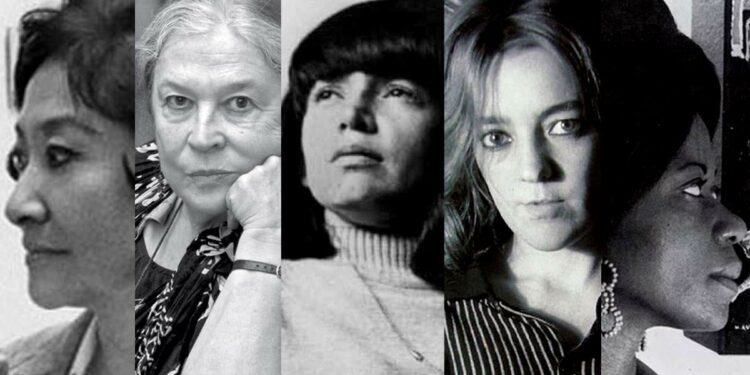

The artists on this list have used their art to challenge the status quo, they have led the way in emerging art movements, and have created engaging artworks in the process. These five women artists established themselves as visionaries in their respective fields and have made strides in Latin art. Read on to learn more about Beatriz Gonzalez, Marta MinujĂn, Tilsa Tsuchiya, Paz Errázuriz, and MarĂa Auxiliadora da Silva.

Â

1. Beatriz Gonzalez

Study for Interior Decoration, Beatriz Gonzalez, 1981. Source: De Pont Museum, Tilburg.

Â

Colombian artist Beatriz Gonzalez creates art that reflects the transformative events that have occurred in her country since La Violencia during the 1950s. Gonzalez’s works are an ironic take on the censorship of art, the influx of mass media from Western influences, and how this has impacted the way art is perceived in Latin America. Her appropriation of iconic Western iconography including Sun-Maid Girl in Sun Maid and paintings such as Leonardo’s The Last Supper or Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass, are re-interpreted through her perspective.

Â

She does this by using bold colors, abstraction, and mixed media such as bed frames or curtains to act as the canvases or frames for her paintings. Her art inspires viewers to question what is tasteful or cursi (corny/kitschy) by blending everyday household objects with traditionally accepted imagery from fine art. The consumption of both popular reproductions of art and the photos in news media were both major focal points in her pieces. She is also known for creating works inspired by tabloids or magazines. She creates dark-humorous prints about British royalty, socialites, presidents, and religious figures. Her striking juxtaposed images make the viewer reinterpret iconic works through a different lens.

Â

Beatriz Gonzales. Source: Tate, London.

Â

Gonzalez’s work shifted from the mid-1980s and onward, particularly after the massacre at the Palace of Justice in 1985, seen in her painting Mr. President, What an Honor to be With You at This Historic Moment I and II, criticizing the government’s response to the violence. She started to focus on work that featured a much darker tone, including Self-portrait While Crying, Camouflaged Apocalips, and most recently Anonymous Auras at the Central Cemetery of Bogotà .

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

Please check your inbox to activate your subscriptionThank you!

Â

These works covered the violence associated with the paramilitaries, the military, and drug traffickers in Colombia with graves, coffins, and weeping figures being a common feature. The presidency of President Julio César Turbay Ayala was also a major subject in her art. She created a body of satirical work that documented her view of his presidency. The most notable one is the image of Turbay in Interior Decoration, printed on a 450-foot-wide curtain, demonstrating the stark contrast between his personal extravagant life with the persona of his public one. Gonzalez’s intent to tell forgotten stories can be seen in one of her earliest and most referenced works, The Suicides of Sisga series where she was inspired by a hazy newspaper photograph announcing the news of a young couple’s suicide. It resulted in a poignant portrait of a couple whose story was almost forgotten, yet it is still one of her most referential works.

Â

2. Marta MinujĂn

La Menesunda, Marta MinujĂn and RubĂ©n SantantonĂn, 1965. Source: Wikipedia

Â

The career of Argentinian artist Marta MinujĂn encompasses a body of work that has captivated audiences for decades. Her art is very self-aware of popular trends and events, particularly in the media, and she creates interactive pieces as a way to capture the public’s interest and participation. While studying in Paris, some of her earliest works included using Colchones (mattresses) which were painted in bold-colored vertical neon stripes, a signature for the artist, creating soft voluminous sculptures while her Cajas (boxes) became concealed with slogans from advertisements.

Â

Her happenings (her early performance pieces) including Room of Love, allowed participants to enter and play inside an amorphous sculpture of mattresses while in Destruction her mattress pieces were then destroyed by her peers. Upon her return to her home in Buenos Aires, MinujĂn began creating pieces that were meant to be interactive with her audiences. Her collaboration with the artist RubĂ©n SantantonĂn created La Menesunda (1965), which was an interactive environment made up of several staged rooms where viewers would encounter a real married couple laying in bed, a beauty parlor where participants could get their makeup done, and various others that engaged with and enticed the senses of the audience.

Â

Marta Minujin. Source: The New York Times

Â

MinujĂn challenges the notion of how art is shared and distributed. She has created different larger-than-life versions of large-scale replicas of famous structures. Once the sculptures are built they are then dismantled, allowing the public to take the items from these structures once the presentation is complete. Pieces in her The Fall of Universal Myths series include The Obelisk of Sweet Bread in Buenos Aires which was made from sweet bread, Books Parthenon (Argentina) made from banned books in Argentina during the late 1970s/early 80s, or The James Joyce Tower of Bread, also made from bread.

Â

This process of creation and destruction is a large part of her work. MinujĂn dips back into her own artistic history to create reiterations of past themes, or artworks. While her art lives on in film and photographs, the in-person experiences last longer, as they continue to inspire and intrigue a new generation of participants. La Menesunda was reconstructed in 2015 at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires and the New Museum in New York. Her Sculpture of Dreams is also a large inflatable sculpture version of her early Colchones.

Â

3. Tilsa Tsuchiya

Mujer Volando, Tulsa Tsuchiya, 1974 Source: Christies

Â

Tilsa Tsuchiya Castillo was a Peruvian painter who is considered one of the great masters of modern art in Peru. After winning a scholarship upon graduating from the Escuela Nacional Superior AutĂłnoma de Bellas Artes (ENSABAP), she studied in Paris at the Sorbonne and the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Upon her return to Peru, the culmination of influences from multiple cultures appeared in her later works. These included the European art movements she experienced while in Paris, but also the Indigenismo art movement and Quechua mythology in Peru.

Â

Her paintings may appear fantastical, but to her, they are very real in the sense that they are derivative of her multicultural background. Born in Supe, she grew up during the decades of World War II and was a part of the Japanese migrant community, or Nikkei community, in Peru. With the struggles that came from living in a society that discriminated and ostracized people of Japanese descent in Peru. Her works are representative of the fact that she was a Peruvian with both Asian and Latin American roots. Her Mitos (Myths) series was inspired by Peruvian myths and traditional storytelling.

Â

Fantasia II, by Tilsa Tsuchiya Castillo, 1973. Source: Sotheby’s

Works from this series include the paintings Myth of the Red Warrior and Myth of the Woman and the Wind. The Andean mountain landscapes are dominant features in her works as seen in The Myth of the Red Warrior. The background resembles the distinct mountain landscapes of Cusco with its angular and vertical peaks. The distinct haziness of her work is created by the thin linework and soft application of colors by using sfumato and glazing techniques. This is also seen in her human forms which have a soft fleshiness and evanescence with voluptuous and swelling bodies, particularly in Tristán and Isolda and The Flying Woman.

Â

Some of them have facial features that appear to be similar to masks from Pre-Columbian art while others have no heads or arms. Because of this, the rest of their bodies seamlessly blend into the earth and sky. Her animals, plants, and human figures congeal into one another and coalesce into totem-like structures or mountainous structures. She has translated her art into other mediums as well. These images are featured on the ink illustrations that she painted onto stones. Her work has been used in the illustrated book of poems Noé delirante, by her friend the poet Arturo Corcuera. It was announced that her artwork would be featured on the Peruvian 200 soles bill note.

Â

4. Paz Errázuriz

Evelyn, From Adam’s Apple, Paz Errázuriz, 1983. Source: Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

Â

Paz Errázuriz is a Chilean photographer whose works contradicted the social and political norms of the Pinochet military coup and dictatorship. Her portraits document the lives of those who are largely ignored or neglected in both art and the news. During this period, her photography became a tool of protest and resilience. Her 1980s Adam’s Apple is one of her most recognized works where she documented the lives of transgender women and cross-dressing men, some of whom worked as sex workers in the brothels of Santiago and Talca.

Â

In these portraits, Errázuriz established relationships and gained the consent of her subjects during this process, taking the time to understand the people whom she was documenting. Through her work as a photographer, her intense interest in and study of people has allowed viewers to see the personal identities of marginalized people in society. Her Sleepers series documented the lives of people living in homelessness during a period of economic upheaval in Chile. In Myocardial Soul she photographed couples who were in a psychiatric hospital in Putaendo. She also focused on various professions, such as Santiago circus workers which can be seen in the Circus series, boxers in the Boxers series, and professional wrestlers in the Ring Fighters series. The people in these photos gave a behind-the-scenes look into their lives.

Â

Adam’s Apple, by Paz Errázuriz, 1983. Source: Tate, London.

Â

In her Bodies series, Errázuriz confronts the viewer with the perceptions, or misperceptions, of people’s physical appearances. Her portraits feature nude elderly participants and it is meant to re-conceptualize what is considered beautiful and desirable. She has also worked to document ethnic groups whose livelihoods were, and currently are, under threat. In Nomads of the Sea, she shows the Alacalufe people, who live in the Southern Patagonia region of Chile. It took years for Errázuriz to gain the trust of her subjects, but her practice is representative of the fact that it is respectful of the people whom she documents.

Â

For The Sepur Zarco series, Errázuriz traveled to Guatemala to document the women of the Q’eqchi’ community, known as The Grandmothers of Sepur Zarco, who were subjected to crimes of rape and enslavement by the military personnel during the civil war. The groups of people she has documented over the past decades have suffered violence and ridicule, and have been misunderstood by institutions and governments. However, she does not portray them in these situations. Instead, because she spent the time getting to know them and by building trust, she captured images that are familiar, rather than foreign.

Â

5. South American Artist MarĂa Auxiliadora da Silva

Chuva Sobre SĂŁo Paulo (Rain over SĂŁo Paulo), MarĂa Auxiliadora da Silva, 1971. Source: Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

Â

Brazilian artist MarĂa Auxiliadora da Silva created art that reflected the history, daily life, and experiences of Black communities in Brazil. Her mixed-media oil paintings are richly vibrant in color and texture. Because of her embroidery skills, her paintings contain detailed patterns and linear brushstrokes, almost as if they were stitched on, rather than painted onto the canvas. The inclusion of her own hair into her paintings, along with thickly applied paints and Wanda putty, also creates a raised surface and texture to her works.

Â

MarĂa came from an artistic family and worked with artists in the Black communities of SĂŁo Paulo. Her mother was also an artist who taught her embroidery, her father a musician, and her siblings worked in artistic mediums as well. Her painting Studio of Art and Family shows the artist in her studio with her brother producing wood carvings. The recollections of the stories that her mother told her of life in Minas Gerais before her family moved to SĂŁo Paulo are seen in paintings like Fazenda and Plantação. These are scenes of the rural life of farm workers, particularly during the harvest season, and their communities. She is also well-known for her urban scenes of life in SĂŁo Paulo which can be seen in Amusement Park and Rain Over SĂŁo Paulo. Both are full of lively interactions between people demonstrating the busy life of the city.

Â

Portrait of MarĂa Auxiliadora da Silva. Source: AWARE

Â

Da Silva’s paintings depicting Capoeira are powerful because they contain scenes of activities that were considered criminal in Brazil. She also created paintings that incorporated Afro-Brazilian religions and imagery such as portraits of orixás (orishas), Candomblé, and Umbanda. Incorporating the traditions and practices developed during/after slavery makes them reminders of a time of resistance and survival of her community.

Â

These traditions as well as scenes of Carnival, and Samba dancers are also seen in paintings like Bar with Gafieira, June Celebration, and Carnival. She is known for her romantic paintings which include scenes of couples passionately engaging in kissing and dancing. One of these is Theater which shows a scene of couples embracing while watching a romantic movie. Some of her paintings also contain quadrinho or comics-like bubble air quotes that show the conversations between them.

Â

She created self-portraits of herself as a working artist seen in the paintings Studio of Artist and Family and Self-portrait with Angels. In the latter, she depicts herself painting surrounded by floating angels acting as guides or muses and a garland of flowers. Silva suffered from cancer during the last years of her life. This is depicted in paintings such as Bride’s Wake or Self-portrait with Angels. In Bride’s Wake, she painted herself as a bride dressed in white at her own funeral with onlookers weeping around her.

Source link : https://www.thecollector.com/female-artists-south-america/

Author :

Publish date : 2024-07-02 12:15:27

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.