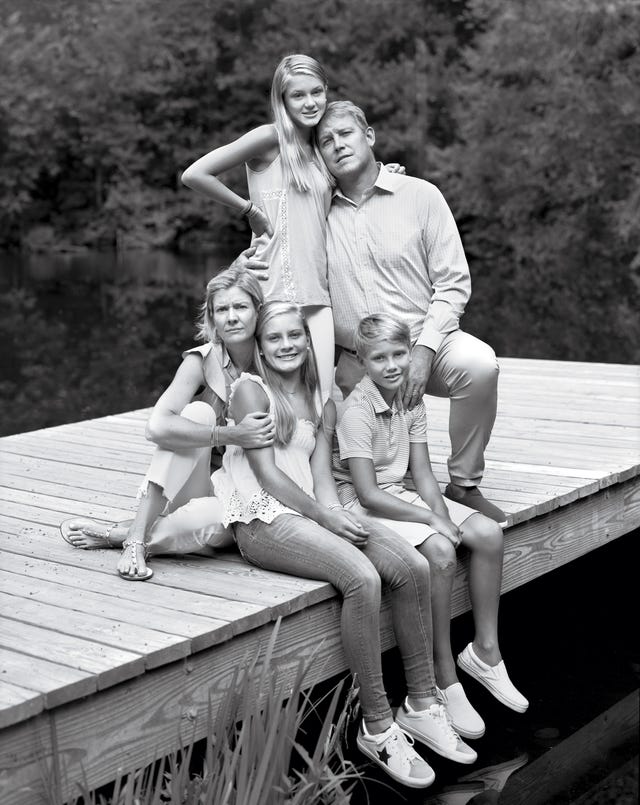

The man stands in the park, reenacting a scene from his own life. He is in the park with his family, and they are pretending to be themselves, doing things they normally do: playing games, walking on the grass. But they are not themselves. And this is not normal. But his lawyer said it was a good idea, so here they are.

In the middle of a sea of green athletic fields, dense woods, playgrounds, tennis courts, and a pond, he stands in the shade of a gazebo behind a field where his children compete in sports—a field where, as a boy, he himself competed, a field he knows better than his own back yard. His two daughters fling a lacrosse ball back and forth, back and forth.

“Lacrosse is like a religion around here,” the man says. All three of his kids play in lacrosse leagues after school.

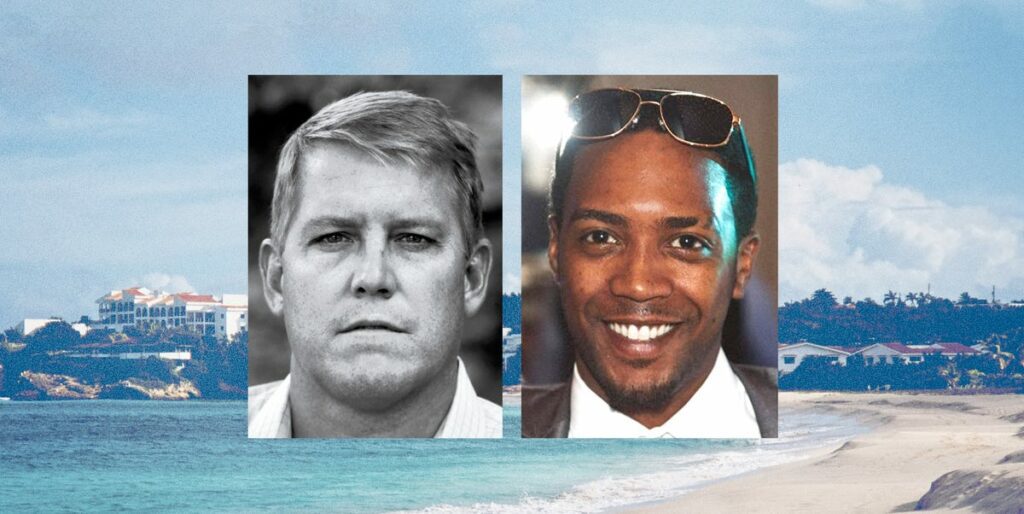

There’s a photographer taking pictures of them, and the family has an easy rapport as they stand before the camera. “Should we smile?” asks Kallie, the man’s wife—a good question, all things considered. The photographer is taking their picture because of what happened when they were on vacation in the Caribbean and the man, Gavin Scott Hapgood, was accused of causing another man to die. Now they want people to see that despite that awful nightmare they are a good family. This photo shoot is one small part of what they see as their fight for survival.

Scott and Kallie Hapgood met freshman year at Dartmouth, and they have been married for 17 years. A college athlete, Scott has worked in finance at UBS for two decades. The Hapgoods live in the town where Scott grew up, Darien, Connecticut, and have three children, two girls, ages 13 and 11, and a boy age nine.

The man, who goes by Scott, met Kallie freshman year at Dartmouth. They have been married for 17 years. Scott, who just turned 45, has worked in the same industry, finance, for the same company, UBS, for more than two decades. Kallie, 44, is head of investor relations at the private equity firm Gridiron Capital. They chose this town, Darien, Connecticut, the ninth-wealthiest town in the United States—the town where Scott grew up—to raise their three kids in, two girls, ages 13 and 11, and a boy age nine.

The TV show Billions portrays commuter-rail Connecticut as the province of swashbuckling mandarins who inhale sushi and guzzle Macallan between bouts of corporate warfare. And in real life, things to do in Darien include the annual Ox Ridge Hunt Club Charity Horse Show (established 1931) or a round of golf at the members-only Wee Burn Country Club (founded 1896).

The Hapgoods live in a different world from all that, albeit an adjacent one. Darien is a family town where car-seated minivans share driveway space with Porsche 911s and Audi A8s. People raise kids hands-on, in stately old homes, and spend time with other parents. Social life revolves around Little League and private school fundraising galas and the PTA, with harried stops at Shake Shack in between.

You can plan all you want. Scott’s life has moved along tracks grooved deep over decades: from the suburbs to the Ivys and back to the suburbs, a family and a job and a big house. But there are so many humans running around the planet, and sometimes two of them collide unexpectedly, at just the wrong angle in the wrong millisecond, and it causes an explosion. That’s what happened on vacation in Anguilla: Scott ended up in a hotel room 1,800 miles from the town where he grew up, and in that room was a stranger, a younger man named Kenny Mitchel, and pretty soon the other man was dead.

Scott Hapgood’s rectilinear face rests on a tree-trunk physique maintained by the doubles paddle tennis league he and Kallie compete in (and dominate). He was a first team All Ivy defensive end and a second team All Ivy lacrosse player. Today he’s a tanned, six-foot-three avatar of suburban masculinity, with a Mt. Rushmore brow, thin lips, and cropped sandy hair, in button-ups and khakis and breathable mesh loafers. His handshake is firm, even though the pinkie of his right hand juts out at a strange angle, the result of an old sports injury. Nothing else is out of place. In photos Scott appears every inch the Ivy League alpha male that his résumé suggests.

In person the stereotype falls away. Dark circles have appeared under his eyes. He speaks in clipped sentences, with visible tightness at the corners of his mouth. A week before the shoot, at a grim press conference, he called his life a “living nightmare.” Only around his family does the pre-Anguilla Scott emerge. As he stands within the force field of their affection, his warm smile melts away the tension curdling behind his jaw.

It’s been hard for the kids to process what they witnessed—to be witnesses, in fact, giving statements to the police in what would become the investigation of their father. They have been in therapy. Scott and Kallie have been open about what happened, and what’s happening now. “The kids are holding up pretty darn well, but there’s little things you notice,” Kallie says. At the moment, here in the park, they seem to be in a good mood.

“I promised them ice cream afterward,” says Scott, smiling.

Kenny Mitchel was born on the Caribbean island of Dominica, where he grew up with two brothers. His parents split when he was young. “He was their favorite,” says a close friend, who spoke on condition of anonymity to protect his job. “He was very much loved by his family.”

After his father moved to Anguilla to pursue business as a contractor, Kenny often traveled back and forth between the two islands. In 2015 he moved to Anguilla for good, to follow in his father’s footsteps.

He made friends almost immediately. He loved cooking, eating, dancing, and making music. Kenny could throw a barbecue with no warning, and fill up a yard with people at the drop of a hat, the friend says. “He would say, ‘I’m going to grill up some chicken, invite everybody to come. He loved to see people having a good time.’”

Kenny Mitchel was originally from the island of Domenica but had lived in Anguilla since 2015. He was funny and gregarious, an enthusiastic host who loved to dance. He and his girlfriend, Emily Garlick, have a daughter, who turns three this month.

A year after he moved to Anguilla, Kenny met a woman named Emily Garlick at a food festival where she was working. He loved food, and Emily caught his eye; he hung around her booth all day, smiling at her. She flirted, told him to go away, thinking he was “too small, too little.” But her friend put Emily’s number in Kenny’s phone, “and that was it.”

Kenny was wiry, with dark skin and a gentle, handsome face. Garlick—white, British, red-haired, blue-eyed, her face an ocean of freckles—fell hard. “He was caring. He was passionate—about everything: his music, his food, me, his family, how he looked,” she says. “He loved to look sharp, funny, goofy. He loved to dance. He was a bit silly. A good one.”

She recalls one of their early dates, when they spent a weekend together on the beach, and he wrote her a song on the spot. She remembers it perfectly:

When you look into the sky,

Have no wings but wish I could fly

Not gonna lie, I lost a few close friends

And I’m not afraid to cry,

Beautiful girl on the beach has got some beautiful eyes…

After two dates they were a couple. “Four months later,” she says, “we were pregnant.” They moved in together. Mylie—a combination of “Emily” and Kenny’s nickname, Mylez—was born in February 2017.

Kenny was obsessed with his newborn daughter, Garlick says. “He was great—he knew his responsibilities and he did them. I’ve got videos of him playing with her all the time… He did feed [her] through the night. He changed nappies.”

Supporting his family was important to Kenny, but it wasn’t always easy. His father made good money as a contractor, and Kenny had followed him into that line of work, taking on odd building jobs. Then, in September 2017, Hurricane Irma wiped out homes and caused millions of dollars in damage on Anguilla. Malliouhana, one of Anguilla’s preeminent luxury hotels, was hit badly. Kenny got a job there as a maintenance worker, repairing broken railings, repainting walls, and doing electrical work. He was earning around $2,000 a month and he loved the work, according to those who knew him, and he began to allow himself to dream of bigger things: college abroad, his own landscaping business.

Still, his relationship with Garlick was often tumultuous. They argued, broke up, and made up. Love for Mylie held them together, until it didn’t.

On March 25, 2019, less than three weeks before he died, Kenny was arrested and charged with raping Garlick.

At the time of his death he was out on bail, with a protective order keeping him from seeing Garlick or his daughter. Garlick now flatly denies that he raped her, and the facts of that incident remain murky. “He never laid a hand on me,” she told Town & Country, adding that Kenny was never once violent with her. “He didn’t know how to be violent,” she said. Still, she later confirmed that she had been the one who called the police that day, leading to his arrest. After several requests, she declined to elaborate further.

Whatever had happened, she said, was between her and Kenny. Plus, “It didn’t define him. He didn’t deserve to die.”

On the night of April 12, 2019, Kenny went out with his close friend, who recalls his being in good spirits, talking about the future. He mentioned that he had just gotten paid, and paid his bills, earlier that day.

“You said to me when you left my car the night before your passing ‘Aye frère, I love you, eh,’” the friend wrote online shortly after Kenny died (the two often spoke Dominican Creole with each other). “At least you passed knowing that I loved you and appreciated you the same.”

Anguilla has dozens of beaches, but Meads Bay Beach, a cartoonishly perfect milelong strip of pale sand on the western tip of the island, is where most visitors stay. They book rooms in one of its upscale hotels, the easternmost of which is Malliouhana, a cluster of bone-white buildings perched on a rocky bluff. It opened in 1985, and its spa and world class French-Caribbean restaurant helped spur an explosion in luxury tourism to the island. After closing in 2011 for a multimillion-dollar renovation, it was reopened four years ago by Auberge Resorts, an international hospitality management company that operates 19 properties on three continents. In high season a single room at Malliouhana can cost $1,000 a night; a suite runs upward of $1,800.

For their spring break in 2019, Scott and Kallie Hapgood decided on a trip to the Caribbean island of Anguilla. Neither Scott nor Kallie had ever been there. The website of international hotel conglomerate Auberge Resorts describes its Anguillan property, Malliouhana, as “modern day island glamour set atop a bluff that rolls down to pristine white sands and azure-blue sea.” A suite for the family would cost around $1,800 a night.

Scott and Kallie knew none of this when they booked their seven-night stay. Amid the constant logistical tangle of school, sports, and work, the Hapgoods had little time to debate vacation destinations. They went to a travel agent and picked Malliouhana at random from a menu of options, as if “throwing a dart at a dartboard,” Scott would say later.

In addition to nice hotels and pristine beaches, Anguilla, population 15,000, is known for its friendly locals. The crime rate is low compared with other Caribbean islands. People leave their homes unlocked. Tourism is the economy, and guests are greeted with smiles. Many are American, and, as is the case at most Caribbean resorts, nearly all are white.

The first thing that happens when you set foot in Malliouhana is someone hands you a rum punch. Breezes blow fragrant air through the open lobby, past sea-green columns, between potted palms, over mirrored floor tiles, past framed tropical scenes by the Haitian painter Jasmin Joseph. A smiling attendant leads you onto the veranda, where sunburned pink flesh sinks into pristine white couches. Beneath you the ocean stretches for miles.

The Hapgoods wasted no time enjoying Malliouhana on their first morning. They picked their way to the beach for an early swim, down a narrow staircase hewn from the cliff face with a plastic guardrail. Staffers in uniform handed out sunscreen and towels.

Kenny was supposed to start work at 8 that morning, but according to Scott’s lawyer, Juliya Arbisman, Kenny’s supervisor, Eduardo Urquiza, later told police that Kenny reported two hours late, around the time the Hapgoods were swimming.

Inside the Malliouhana Resort lobby. In addition to nice hotels and pristine beaches, Anguilla, population 15,000, is known for its friendly locals. Tourism is the economy, and guests are greeted with smiles. Many are American, and, as is the case at most Caribbean resorts, nearly all are white.

After their swim, the family walked back up to the hotel for lunch; Kallie and the kids ordered virgin daiquiris. Most of the resort’s employees are native Anguillans or transplants from other Caribbean islands. They wear straw hats and striped T-shirts and toothpaste-green board shorts, filling drinks, folding towels. They smile knowingly at the roosters that peck food off plates, and they ask guests if they’d like a Carib beer, or perhaps they might want to try a lychee?

Several Malliouhana employees said they recalled seeing Kenny working by the pool on the first day of the Hapgoods’ visit, and when they greeted him he seemed normal. One employee remembered seeing the Hapgoods and Kenny in the pool area around the same time at midday—the Hapgoods were eating lunch; he was painting a wall. They were separated by perhaps 30 yards, and she didn’t see any interaction between them.

Kallie checked out snorkeling equipment after lunch, and the family swam amid schools of blue tang and parrotfish, five blond heads bobbing in the surf, the tangle of their overbooked suburban lives dissolving into the sea.

Afterward, Scott and the kids trudged back up to the pool, while Kallie went to return the snorkeling equipment. Sleepy from the afternoon sun, Scott decided to return to the room. The Hapgoods were in room 48–49, a pair of adjoining suites configured into a larger suite with two bedrooms connected to a central sitting area. The suite was in a one-story building at the edge of the property, about 100 yards from the pool.

Scott walked along a footpath, winding through a manicured grove of papaya and hibiscus. Black roosters strutted on the grass, and emerald lizards scurried into the underbrush.

According to Arbisman, Urquiza, Kenny’s direct supervisor, scheduled Kenny to fix fans in a restaurant kitchen in the afternoon. But for two hours he was unaccounted for, and he never completed the assignment.

Scott flopped down on the king-size bed, flicked on the TV, and found the Masters golf tournament. Not long afterward, his daughters returned.

A few minutes later, Scott heard a knock at the door.

This is what Scott says happened next: When he opened the door he saw a hotel employee—black, slight of build, and several inches shorter than himself. A man he would later learn was Kenny Mitchel. Kenny explained that he was there to fix a broken sink, Scott said. Scott hadn’t reported a broken sink, but the guy was wearing a uniform, and he let him in.

He led Kenny to the bathroom, then went to the room his daughters were in to let them know someone else was there. He heard a noise behind him. He turned around. There was Kenny, he says, who pulled out a knife and said, “Give me your money. Give me your wallet.”

Scott says he told Kenny to calm down, but Kenny held the knife up and repeated, “Give me your money. Give me your wallet.” Scott grabbed Kenny’s arm and wrist with both hands to get the knife from him. The men fought.

The brawl moved into the bathroom of room 49. Scott ended up on top of Kenny, straddling him on the cold tile of the bathroom floor, his arms pressing on the smaller man’s chest. His daughters ran for help, yelling that their father had been attacked.

Geshaune Clarke, 27, was working at the Malliouhana as a bellhop, his station a few yards from the front desk. This is what Clarke says happened next: He saw two children approach the desk and speak frantically to the attendant there. He couldn’t make out what they were saying, but his supervisor emerged and told him to go to room 48. He rushed there with Urquiza. Clarke found the door open; it had been propped ajar in a specific way that only employees use.

Nobody was in the room.

The door to the adjoining room was locked. Clarke says he heard several thumps from the other side of the door. He told Urquiza, who had a master keycard, to unlock room 49. Clarke says that a later review of records showed that this key swipe took place at 3:53 p.m., and that he was the first one in the room. He saw a trail of blood leading from the bathroom, a few feet from the entrance. He looked inside, and his eyes locked with Scott’s. Then he looked down and saw Kenny beneath Scott on the floor.

Geshuane Clarke in Anguilla on May 23, 2019. He was working at the Malliouhana as a bellhop when the Hapgoods checked in, and he and Kenny were friends. He was the first person into the hotel room after the Hapgood children went to the front desk for help. When he entered, he saw saw Kenny beneath Scott on the floor.

Kenny and Clarke were friends. They socialized and made music together, sometimes hanging out at Waves, a beach bar managed by Emily, Kenny’s girlfriend. Scott’s right arm was over Kenny’s chest, holding him down. His left forearm was pressed down over the right side of Kenny’s neck and collarbone, according to Clarke.

“He came at me with a knife,” Scott said.

Urquiza immediately went over and pressed down on Kenny’s limp hand and foot. He wanted to demonstrate that he was there to help Scott restrain the man.

“He came at me with a knife,” Scott said again. Clarke didn’t see Kenny move at all. Scott continued talking, explaining that Kenny had asked him and his daughters for money. “You need to get that knife,” he told Clarke.

Clarke walked past the bathroom and down the few steps into the bedroom, where he found the knife on the ground next to the TV. It was Kenny’s Leatherman utility knife, a tool he used regularly in his maintenance duties. The blade was half folded, in a V-shape; Leatherman blades lock into place when extended, meaning it was either intentionally partially folded or had been jarred by an impact. He doesn’t recall seeing blood on the blade.

Clarke placed the knife on a table and returned to the bathroom. He didn’t see Kenny moving, or even drawing breath. He asked Scott to get off the prostrate man. According to Clarke, Scott refused, replying that he had just been attacked. “I do understand,” Clarke recalls responding, “but you need to allow him some airway breathing space.”

When Clarke had first entered the room, he says, Scott seemed shellshocked, off-kilter, wired by adrenaline. But when they asked him to get off Kenny, he recalls, “everything changed.” Scott grew angry. He refused to budge and said that Kenny was breathing just fine.

“I can feel his stomach moving,” he said.

“You could stay on him for restraint if you like,” Clarke shot back, “but you need to get off of his airways.” Scott barked at him, asking if he knew what it felt like for someone to attack him in his room on vacation and ask for money. “He was rambling a lot,” Clarke recalls. “He had the floor most of the time, you know?”

Scott set conditions, according to Clarke: He would get up if the police or security came, or if they could find something to tie Kenny up with. Scott later told T&C, “I was repeatedly saying we need to get him into handcuffs because I was frightened he had more weapons on him.”

After they explained that they were hotel employees, and that Kenny worked under Urquiza, the manager, Scott told them that he couldn’t trust other workers in uniform who might have been affiliated with Kenny. Clarke and Urquiza kept trying to convince him to give Kenny more breathing room, but Scott resisted, reiterating that he wouldn’t do so until Kenny had been tied up or the police had arrived.

Clarke was fed up. He had had some medical training for a part-time job as a dental assistant. He knew basic emergency protocols and could see that Kenny was in distress. The man was struggling to breathe, his breath coming out raspy, fluid seemingly pooling in his esophagus. Clarke raised his voice for the first time, demanding that Scott get off Kenny. Scott shot back, asking Clarke to imagine himself in his position—how would his daughters feel if he got off Kenny? How could he understand?

Clarke responded that he did have a son, so he could understand. He still wanted Scott to get off Kenny.

“I don’t want to speak to you anymore,” Scott said. “You need to leave.” This upset Clarke; Urquiza gestured for him to calm down, and he did. Scott repeated that he wanted Clarke out of his face. So Clarke left the room and went to look for duct tape to restrain Kenny with. Clarke was so angry by this point that he considered grabbing a two-by-four to whack Scott so that he’d get off his friend. But he didn’t, and after a few fruitless minutes of searching he returned to the room.

“Who are you?” Scott asked, looking at Urquiza. “And who is he?” he asked, meaning Kenny. Urquiza explained that Kenny worked for him. “I really don’t trust you guys,” Scott repeated. By this point Clarke and Urquiza had been in the room for around 10 minutes.

Kenny shifted his head and rasped, “Can I speak?”

Scott looked down at him. “You don’t have a fucking thing to say,” he said, and pressed down hard with his forearm. Scott told T&C, “I could feel him breathing beneath me the entire time.”

That was the last time Clarke saw Kenny move.

Just then, Kallie burst through the door. When she saw the scene in the bathroom, she was shocked, and she asked Scott if he was hurt.

Scott said he was okay.

Kallie turned to Clarke and Urquiza, demanding to know where the police were. “If you guys don’t get the cops down here, this is going to be all over the United States news,” she said, holding her phone.

She asked Scott if she should record a video of the scene. “No need to,” Scott said.

Around this time, which Clarke places at somewhere between 4:15 and 4:25, two security guards entered the room. Urquiza asked one of them to help restrain Kenny, while the other went outside to speak with the police on the phone.

When Scott saw the towering security guard, he said, “You’re a big guy. You can hold him now.” He stood, left the bathroom, and went to the other bathroom, in 48, to wash the blood from his wounds.

Clarke entered the room where the security guard was kneeling next to Kenny. They rolled him onto his side, hoping to make it easier for him to breathe. Blood and saliva dribbled from his mouth. They could see he was breathing, but barely. Clarke felt for a pulse—it was faint, and slow.

The police arrived two to three minutes later. Kallie would tell the New York Post that an officer looked at her and said, of Kenny, “We know him. He is a bad guy. He was just in our custody”—an apparent reference to his arrest for raping Garlick.

Clarke helped EMTs load Kenny onto a stretcher. Clarke asked Kenny to give him his side of the story, but he got no response. Clarke didn’t see any breath fogging up the plastic mask over his friend’s mouth.

A few hours later, Kenny was declared dead.

Scott was treated for his injuries at the hospital—he later released photos of himself showing bloody lacerations on his nose, ear, and chest. He gave a statement to the police and spent the night at the police station.

Malliouhana got a room for the Hapgoods at the Four Seasons Hotel, on the far side of Meads Bay Beach. The next day, Scott recalls, Malliouhana’s general manager, Kapil Sharma, met the Hapgoods in person, apologized, and said he couldn’t “imagine what we were going through, especially because he also has children.”

The Hapgoods spent as much time together as possible over the next two days. On April 16 Scott was arrested. Kallie called Sharma, asking for help. “In a very brief phone call, he told her he could not help us,” Scott recalled. “We haven’t heard a word from anyone at the resort since.”

Her Majesty’s Prison, where Scott Hapgood was held after being charged with manslaughter. He was granted $74,000 bail on the condition that he come back for future court dates. He an flew home on a private jet arranged by friends less than a week after Mitchel’s death.

Scott was charged by a magistrate with manslaughter and sent to the prison, a mint-green building with high walls just across the street from the courthouse. He was escorted into the building in handcuffs, flanked by two large police officers. Within a few hours his lawyer got his case in front of a judge, who granted him $74,000 bail, citing “inflamed passions of the general public” and the “almost imminent likelihood of public unrest.” It was also confirmed at the bail hearing that several of Kenny’s relatives and citizens of Dominica worked at the prison, so it might not be safe for Scott to remain there.

As a condition of his bail, Scott promised to come back for future court dates, and he flew home to Connecticut with Kallie on April 18 on a private jet, “arranged for and paid for by the generosity of the people that touch our lives every day,” he said later. His children had flown home separately on April 17 with a family friend from Darien who had been vacationing on the island.

Furious Anguillans lined the streets near the airfield, snapping photos as Scott’s plane lifted off into the sky.

Kenny Mitchel was given two funerals, one in Dominica and one in Anguilla. Hundreds of mourners cried and sang his praises, many wearing shirts that read “Justice for Kenny” alongside an image of his face.

The initial reports of Scott’s arrest sparked frenzied gossip not only in Darien but in New Canaan, Greenwich, and Stamford, the insular communities of Connecticut’s finance belt, where it seemed everyone knew someone who knew someone who knew the banker charged with manslaughter.

How big was the news? “Huge,” says the captain of the fitting room at the Brooks Brothers in Darien. “They thought it was very strange that that would happen to someone from around here.”

Within days, segments about Scott were running on the nightly news, and newspapers in Connecticut covered his situation closely. Armstrong Williams hailed him as an “American hero” in National Review, and Nancy Grace devoted an episode of her podcast Crime Stories to the case. Scott was placed on administrative leave by UBS, which released a statement saying they were “aware” of what happened in Anguilla and “following the situation closely.”

In Anguilla, anger bubbled across social media. Many people were outraged at what to them seemed an obvious case of their government accommodating a wealthy white tourist at the expense of a poor black local. Imagine if a black Anguillan came to America and killed a wealthy white father of three at his workplace, they said. Would he be allowed to leave on bail?

A t-shirt made by Mitchel supporters. Almost immediately after Mitchel’s death, rival groups of Scott supporters and Kenny supporters formed Facebook pages. The Kenny page, known as Unity for Justice, was initially formed to promote a GoFundMe campaign for his daughter. Today the page, which has more than 2,000 followers, is an anonymously run hub for alternative theories about what happened at Malliouhana.

Many did not accept the facts of the case. Why, people asked, would Kenny come into Scott’s room wearing his uniform and pull a knife on him in front of witnesses? He’d lose his job and never be able to work at a hotel on the island again. Wild theories flew on Facebook and at bars, ranging from the vaguely plausible (Scott summoned Kenny to his room to buy drugs) to the far-fetched (it was a tryst gone wrong) to the totally whacked-out (Scott is a Freemason engaged in human sacrifice).

Rival groups of Scott supporters and Kenny supporters formed Facebook pages. The Kenny page, known as Unity for Justice, was initially formed to promote a GoFundMe campaign for Mylie Mitchel. Today the page, which has more than 2,000 followers, is an anonymously run hub for alternative theories about what happened at Malliouhana.

Conversations with many people in Anguilla suggest that the Facebook page’s approach lines up broadly with the suspicions many locals have. Using annotated diagrams of the crime scene, Unity for Justice tries to find inconsistencies in Scott’s public statements.

One post compared photos of Scott’s hair before and after the incident; in the later image his hair seems lighter. “If multiple bleaching attempts are made a participant can remove all drugs from their hair,” the poster wrote. “A worrying situation and one of the reasons why so many ‘blonds’ arrive at sample collections.”

A private page called the Hap Weekly, which has more than 3,000 followers, has served as a hub for support, fundraising, and catharsis among the Hapgoods’ supporters. “Enough is enough. I hope the stinking pile of fossilized reptile shit known as Anguilla gets annihilated by a meteor strike,” wrote family friend Oliver Prichard. “And the dirtbags at the Auberge Malliouhana can go straight to hell.”

Six months after the incident a small crowd gathered in front of Darien Town Hall for a strange event—equal parts press conference, college reunion, and demonstration against the Anguillan court system. There were about a hundred of Scott’s friends and family members, plus a few dozen cameramen and reporters, along with state legislators, aides, and one sitting U.S. senator.

Darien was coming out for one of its own, demanding safe passage for Scott to Anguilla, where he was expected to return in a few weeks. It was October 28; the air had a soft bite.

“It’s hard to recognize people 30 years later—thank god for Facebook,” said a platinum-blond fortysomething woman wearing head-to-toe athleisure. A group of guys in wraparound sunglasses stood on the podium, holding signs that read safe passage and save scott hapgood. A young woman handed out American flags, then shepherded Scott’s family and friends into a clump behind the lectern. “They’re trying to create a camera-ready shot,” said a guy in white chinos, a salmon shirt, and a half-zip fleece.

“It’s so crazy, standing here with everybody I grew up with, under these circumstances,” said a blond woman.

“‘Save Scott Hapgood’… I think that’s the wrong message,” murmured a fiftysomething man, nodding at the sign. “He’s not gone. ‘Stand with Scott Hapgood.’ That’s the proper thing to say.”

“It looks like all men—we need more women up there,” one woman whispered.

“Scott would never get angry,” someone said.

“It’s just terrifying,” Scott’s father Tim Hapgood, 79, told me. “It’s difficult to process it and have a good night’s sleep.” He’s heartened by all the people showing up for his son. “One thing that has come out of this, right from the beginning, is the incredible outpouring of support, love, and prayers. People that I haven’t seen in years—years—reached out to us. So not only do Scott and Kallie have a huge following of friends, but my wife Helen and I do too. That’s the one thing that has really helped sustain us, the support we’ve gotten.”

Scott’s network is wide and deep. He made a few college friends available to Town & Country, and they spoke glowingly: “My son is eight years old,” said Oliver Prichard, who met Scott at Dartmouth and roomed with him later. “If he grows up to be anything like Scott Hapgood, I’ll consider myself tremendously successful as a father.”

After a while the crowd quieted as a parade of elected officials spoke on Scott’s behalf.

“As a parent of five children myself, I know—we all know—that Scott did what any parent would do: protect his children from a highly intoxicated and crazed man,” said Darien First Selectman Jayme Stevenson.

What happened to the Hapgoods was “every American’s worst nightmare,” said Senator Richard Blumenthal, in a navy striped suit with an American flag pin. He said that he’d been working with the state department, Anguilla, and the United Kingdom to guarantee Scott’s safety. “Whatever our differences, we stand behind the Hapgood family,” Blumenthal said.

Eventually Scott took the podium. “As incredibly difficult as this has been, there are days like this when I am reminded how much support we have from friends, family, the community, and our elected officials. The support gives my family strength. We are still in shock that a simple vacation that we had been looking forward to for so long turned into a nightmare,” he said.

His voice cracked when he described the changes to his life.

“I have not been allowed to return to work—where I have worked for over 20 years. I have been disqualified from coaching my kids’ sports teams—which gave me a sense of purpose,” he said.

After he finished, cheers rang out as people wiped away tears.

Emily Garlick doesn’t like to look at Malliouhana, which is challenging, because she can see it from her perch at Waves, the bar her family owns on Meads Bay Beach. Malliouhana looks like a lunar colony, high on a promontory, surrounded by palm trees. All she can think about when she sees it is the father of her daughter, crushed beneath Scott Hapgood’s body, struggling to breathe.

Garlick grew up in Essex, England, the older of two sisters. Her father Steve worked in marketing at a law firm. In 2011 he visited Anguilla and told his wife he wanted to move there; she said they could try it out for six months. Emily and her sister Olivia soon followed their parents to paradise. Eight years later they’re still there. Steve is CEO of Anguilla Finance, an “entity responsible for coordinating the marketing efforts for Anguilla’s international financial services sector.”

Waves is a mellow outlier on the heavily developed beach, not much more than a shack covered in string lights, with a small stage and a kitchen. It hosts local bands several nights a week. Employees from the resorts on the beach come to unwind after their shifts.

At dusk one evening last June, a group called the Decent Ones was playing upbeat soca covers of Adele and Rihanna while a handful of tourists and locals sipped beers and relaxed on lounge chairs in the sand. The only person on the dance floor was Mylie, now three.

“Kenny would be up there trying to grab the mic,” said Garlick, barely holding back tears. “He loved to dance. She dances just like him.” A few minutes later Garlick was bouncing Mylie in her lap and showing her a video of her father, swaying to the music at a crowded party, beaming.

“I’m worried she won’t have any memory of her father,” Garlick said. “She’ll pick up a toy and say she’ll bring it to Daddy, or [on the phone] she’ll say, ‘Hey, Daddy, how are you?’ and hang up. I’ve tried teaching her, you know, ‘Where’s Daddy?’ and she’ll say, ‘In his house in the sky.’ ”

Garlick will soon have the impossible job of teaching her daughter who her father was. “I hope she can dance like him, and I hope she has his appetite, and his passion, his heart,” she said. “She reminds me of him every day—with her eating habits, her dancing, her smile, her nose, her mouth. She has a little finger too on her—just like her father. She’s got big feet like her father. She’ll do things and I’ll burst out crying and have to hide, because she’ll know I’m crying—she’ll wipe my tears away and hug me.”

Night fell. The band played a faithful cover of “No Woman No Cry.” Mylie, swaying softly, gazed out past Malliouhana’s glimmering lights into the soft, black Caribbean night.

“Eventually the anger subsides,” Garlick said quietly. “You have to go back to work.”

On November 18, Scott’s friend Oliver Prichard posted pictures of Kenny taken from his Facebook page, including images of him wearing a skeleton mask, smoking what looks like marijuana, and holding a rifle.

“I really don’t understand why the news media does not publish these photos of Kenny Mitchel,” Prichard wrote.

As the year wore on, members of the Hap Weekly began agitating against Auberge Resorts, Malliouhana’s management company. Unrelated posts by Auberge properties are often flooded with comments by Hapgood supporters, like this one: “I will never step foot in another Auberge resort again. What is happening to the CT family is inexcusable. This resort has been silent as this family endures a nightmare brought on by the resort hiring someone with a RAPE charge and restraining order. Do the right thing and help this family Auberge. Not sure how any of you can sleep at night.”

Some Hapgood supporters have even begun boycotting the chain.

“Auberge owns three posh properties in our region; I hope and pray they vet their employees better than at Malliouhana,” wrote Ann Prichard.

Several Auberge executives did not respond to a request for comment. Reached by e-mail, Malliouhana’s general manager, Kapil Sharma, said, “I have nothing additional to share in this matter, as I have given all of the authorities the information they requested.”

Last summer the Hap Weekly created a GoFundMe page to raise money for Scott’s legal defense, travel, and security in Anguilla. The campaign brought in almost $250,000 in six days.

A sign held by a Hapgood supporter during a rally at the Darien, Connecticut town hall. Last summer friends created a GoFundMe page to raise money for Scott’s legal defense, travel, and security in Anguilla. The campaign brought in almost $250,000 in six days. Members of Kenny Mitchel’s community were outraged. One described it as “the epitome of white privilege.” Another wrote on Facebook, “This is how you buy your way out of murdering someone.”

“Over 500 people donated to Scott’s GoFundMe,” said family friend Tom Ruzzo. “About 25 people contributed to the daughter of Kenny. Dollar amounts aside, that says a lot to me. That’s a character thing.” He did not mention the fact that the population of Darien is larger than that of the entire island of Anguilla, nor the vast difference in disposable income between residents of the two places, nor the sprawling networks a privileged American couple like Scott and Kallie Hapgood are part of—college, the finance worlds of Connecticut and Manhattan, their kids’ schools, a town where he has lived most of his life and where his parents have lived for most of theirs—which have no equivalent on an island territory that’s home to fishermen and hospitality workers.

Members of Unity for Justice were outraged by Scott’s GoFundMe campaign, with one describing it as “the epitome of white privilege.” Another wrote, “This is how you buy your way out of murdering someone.”

In the face of public pressure, GoFundMe pulled the campaign, citing rules about raising money for defense of a violent crime. Eventually the funds were released, after Scott signed a document saying he wouldn’t use them to pay his legal fees.

On August 20, Scott and his lawyer, Juliya Arbisman, held a press conference in New York at which she dropped a piece of news that could completely upend the case. The Anguillan authorities, Arbisman said, had withheld a toxicology report that revealed that at the time of Kenny’s death his body contained cocaine, alcohol, and “other drugs.” She said the report listed his blood alcohol content as 0.19, the equivalent of approximately nine drinks. (The report is not publicly available, and T&C has not been able to review it.)

She also announced that Anguilla’s police chief had issued an Osman warning, which Arbisman described as “an obligation under UK law to provide disclosure and information that there is an existing threat to life.”

On October 1, Stephen King, a pathologist and citizen of St. Lucia who made the determination in the first autopsy that Kenny had died of blunt force trauma and “positional asphyxiation,” reportedly revised his autopsy in light of the newly released toxicology report.

“Acute cocaine toxicity could have been a potentially independent cause of death in the known circumstances,” reads King’s report, dated September 3, according to the New York Times, which claims to have obtained a copy of the report.

In other words, Kenny could have been dying of an overdose—“a potentially independent cause of death”—before he ever reached room 48–49.

Despite the Osman warning, Scott made three trips to Anguilla, as mandated by the attorney general, where he began appearing in a closed hearing before a magistrate. Outside the courtroom in late August, before television cameras and reporters, Scott read a statement: “I’m grateful for the opportunity to appear in Anguillan court today, because every court appearance means we are one step closer to putting this nightmare behind us. A nightmare for my family, but also for the people of Anguilla. We came to your beautiful island for a vacation just like many thousands of others do each year. We came here because of how welcoming you all are. Unfortunately, my family and I were in the wrong place at the wrong time, and in an instant a tragedy resulted which has changed our lives forever.”

He continued, turning his words to the island’s residents: “Lastly, to the people of Anguilla: I understand your anger. I have read the same false facts and untrue stories about what allegedly happened in that room on that fateful day in April. If I lived here and believed those stories, I’d be angry too. But the stories you’ve read and heard are not what happened, and someday I’ll be able to tell the real story in a legal setting. The sooner that day comes, the better.”

After the third hearing, in early September, the inquiry was adjourned until its next phase on November 11. In the meantime the Hapgoods hired Jamie Diaferia, CEO of Infinite Global, an international public relations and crisis firm. On October 14, Kallie appeared on Fox & Friends and pleaded for the government to act, in a segment orchestrated by Diaferia.

After Scott’s third court hearing in Anguilla, the meantime the Hapgoods an international public relations and crisis firm. On October 14, Kallie appeared on Fox & Friends and pleaded for the government to act. “We need help,” Kallie said to hosts Ainsley Earhardt and Steve Doocy. “I’ve seen Trump help Americans in peril around the globe, and we really need help.”

“We need help,” Kallie said to hosts Ainsley Earhardt and Steve Doocy. “I’ve seen Trump help Americans in peril around the globe, and we really need help. My husband is a loving man. He’s never been involved in any sort of charge at all. We’re so fish-out-of-water right now. We’ve never experienced anything like this at all before. He’s a good man, and he doesn’t deserve this. All we wanted to do was take a vacation with our children.”

“You want the president to help?” Doocy asked her.

“Trump—I’ve seen him do amazing things for Americans,” Kallie replied. “And Scott Hapgood is the kind of American you want to help. He’s an amazing father, he’s an amazing friend, he’s a great member of our community, and he needs help. And my poor kids. We’re exhausted.”

Within minutes her message found its mark.

Kallie had appeared on TV just after 6 a.m. At 9 a.m. the president of the United States tweeted a message that seemed to carry a threat to Anguilla, a territory of one of the closest allies of the U.S.: “Will be looking into the Scott Hapgood case, and the Island of Anguilla. Something looks and sounds very wrong. I know Anguilla will want to see this case be properly and justly resolved!”

On the morning of November 11, the air in Anguilla already heavy with heat, the police set up a ring of orange cones around the perimeter of the courthouse, with guards positioned at various points. Only one reporter showed up—me. The only other people there were Kenny’s father Neville, Emily Garlick, and Emily’s sister Olivia. Emily wore a shirt with Kenny’s face printed on it.

“I want him to see my face,” Emily said, explaining that she has shown up every day Scott was scheduled to testify. “He needs to see what he’s done.”

At 9 a.m. a voice rang out from within the squat court building: “Scott Hapgood,” announcing that he was due in court.

Nobody appeared.

“What’s going on? Where is he?” yelled a voice from inside the prison across the street.

“We don’t know!” Garlick yelled back.

The courthouse in Anguilla where Scott Hapgood has appeared several times over the course of 2019. Scott’s future is ambiguous. The United States has an extradition treaty with Britain; if the UK decides to pursue extradition, then according to international law the U.S. government is bound to arrest him and send him to Anguilla to face trial. But extradition cases don’t always work so simply. The state department is a key player in extradition cases and sometimes intervenes.

Forty-five minutes later, with Scott nowhere in sight, the court adjourned for the day. Shortly afterward, Diaferia sent an e-mail to a media list with a statement explaining that Scott had decided at the last minute not to appear in Anguilla after all.

“Scott has cooperated with the Anguillan legal process and has returned to the island three times for hearings in an effort to clear his name,” Diaferia wrote. “But it has become progressively apparent that Scott would not receive a fair trial in Anguilla. During the process, a toxicology report was suppressed, witnesses altered their accounts and submitted new statements that were false, a revised cause of death was ignored, legal counsel was excluded from the hearing, and numerous other actions that suggested that politics are governing Scott’s case rather than the law and the facts.”

A source with first-hand knowledge of the hearings claimed that witnesses said that Kallie bribed the security guard, Louis, who took over the restraint, and that Scott and Kenny were seen talking by the poolside.

Reached via WhatsApp, Louis confirmed to T&C that Kallie had never attempted to bribe him. In interviews, multiple Malliouhana employees who were working at the pool on the day of the attack said they did not see Scott and Kenny conversing.

Diaferia went on to describe how “an inflammatory and false rhetoric has also grown around this case,” noting that in some witness statements submitted by the prosecution, Scott was “referred to as simply ‘the Caucasian’ or the ‘white man.’ These accusations are deeply offensive and wrong. Scott’s race, and Kenny Mitchel’s race, are irrelevant to the facts of what happened.”

The press release went on to note that the Anguillan government had not given Scott the safety guarantee he had asked for, nor had he been guaranteed the ability to return to the United States when the hearing ended. “The guarantees of safety are essential for two reasons,” Diaferia wrote. “First, there is a significant likelihood Scott’s incarceration would be indefinite, as a trial may not happen for many years. Second, there is near certainty the death threats he has received will come to fruition if he were to be held in an Anguillan prison for any length of time.”

“Bullshit,” Garlick said when I showed her the e-mail. “Extradite his ass.”

Dwight D. Horsford, Anguilla’s attorney general, announced that since Scott had violated his bail conditions by not showing up, Horsford would be seeking an international warrant for his arrest that will be circulated through Interpol, making Scott technically an international fugitive.

As of press time, such a warrant had not been issued.

Scott’s future is ambiguous. The United States has an extradition treaty with Britain; if the UK decides to pursue extradition, then according to international law the U.S. government is bound to arrest him and send him to Anguilla to face trial. But extradition cases don’t always work so simply. The state department is a key player in extradition cases and sometimes intervenes. According to Ian Weinstein, a Fordham University law professor who has worked on international extradition cases, Scott has a fair chance of slowing or defeating the extradition process, because he has generated public attention and received the support of politicians. If that happens, the case could be tied up in court for years. Depending on the political calculations of the countries involved, Scott might never go back to Anguilla

In the meantime, in early December Emily Garlick and Kenny Mitchel’s father filed a wrongful death suit against Scott Hapgood—in Mylie’s name, since Emily and Kenny weren’t married.

Garlick still sits for long hours at Waves, trying not to look up at the resort where her daughter’s father said his last words.

Asked if he has explained what is happening to his children, Hapgood says. “We have told our kids everything. Truth and honesty has never been more important in our family, and we are committed to setting that example for them. They have handled it with courage and maturity that has blown my wife and me away. We are in absolute awe of their strength and feel so proud of the people they are becoming.”

Scott spends most of his time in his house in Connecticut, talking to his lawyers and his PR people when he needs to, watching his daughters fling a lacrosse ball back and forth in the yard on mild days. Back and forth. Back and forth.

“I can’t coach anymore,” Scott said on that day in the park, at the photo shoot. “They do background checks, and I’m under investigation. I want to follow the rules.”

The rules have been good to Scott Hapgood. Or, they were good to him for 44 years. Then Kenny Mitchel died. Scott’s decades of planning and training and coaching and working, the Ivy League trajectory, his trust in authority and the law—all of that told him to sit on Kenny’s chest until the police came. And it betrayed him the second Kenny died. The rules contorted into new shapes and hissing chaos coiled tightly around him. Now Scott is some kind of fugitive, and his story suggests that maybe each of us, careful and in control though we think we may be, is always one chance encounter away from a world without any rules at all.

This story appears in the March 2020 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

Ezra Marcus is a reporter and writer whose work has appeared in New York Magazine, Pitchfork, Vulture, Dazed, VICE, FADER, Rolling Stone, The Village Voice, and SPIN.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66b7a5f614034abe8ea47a16538770d2&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.townandcountrymag.com%2Fsociety%2Fmoney-and-power%2Fa30709881%2Fscott-hapgood-kenny-mitchel-anguilla-resort-death%2F&c=7171830589012600023&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2020-02-07 02:15:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.