Americans will observe Columbus Day and Indigenous Peoples Day on Monday.

It is an uneasy pairing. One holiday, observed since 1937, celebrates an Italian who, in making landfall in the Bahamas in 1492, opened an era of European exploration and colonization of the Western Hemisphere. The other honors the Native people who already lived here and, during that era and since, suffered “violence, displacement, assimilation, and terror,” President Joe Biden wrote when he inaugurated the holiday in 2021.

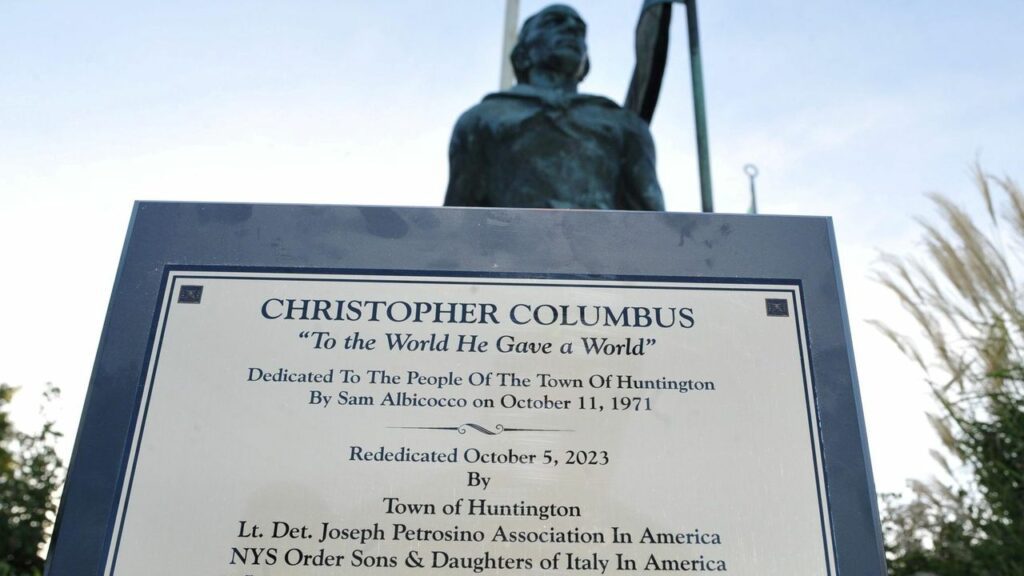

On Long Island, home to 543,332 people of Italian descent and 58,035 people of Native American descent, most town calendars, if they mention the day at all, designate it as Columbus Day; some, like Huntington’s, simply say “Holiday.”

Of Long Island’s 124 school districts, 90 designate the day as Columbus Day on their calendars, seven designate it as Indigenous Peoples Day and 22 recognize both holidays. Sag Harbor recognizes both holidays on different dates. On Monday, Southampton schools will observe Indigenous Peoples Day and Italian Heritage Day.

How many states observe the two holidays?

In 2023, according to the Pew Research Center, New York was among only 16 states and the territory of American Samoa that still observed the second Monday in October as an official public holiday exclusively called Columbus Day.

Four states, two territories and Washington, D.C., marked the day as an official public holiday called Indigenous Peoples Day, or another name recognizing Native Americans. Four other states and the U.S. Virgin Islands marked the day as both Columbus Day and something else. For the remaining 26 states and the territory of Guam, according to the Pew Research Center, the day was “pretty much like any other workday.”

What do Native American and Italian American groups say about these holidays?

In separate interviews, Lance Gumbs, vice chairman and trustee of the Shinnecock Nation, whose homelands are in and around Southampton Town, and Harry Wallace, chief of the Unkechaug Indian Nation, near Mastic and Center Moriches, objected to the observation of Columbus Day.

“It represents a false narrative of what the history of this hemisphere is all about, and it also celebrates someone who we consider committed genocide against the people of this hemisphere,” Wallace said.

Harry Wallace, chief of the Unkechaug tribe, outside of his Mastic office in March 2023. Credit: Newsday/Thomas A. Ferrara

Wallace said he was gratified to see growing recognition of Indigenous Peoples Day, a holiday he said “recognizes the power and existence and contribution of the Indigenous people of Western Hemisphere, our contributions to this land and the origins of our story in our land.”

The success in recent years of state and local efforts to retire indigenous team names and mascots in public schools may mean recognition of the holiday will spread on Long Island, he said.

Gumbs said he favored the approach taken by the Southampton school district, whose calendar no longer honors anyone by name.

Some Italian Americans see the holidays differently. In a 2016 petition for greater recognition of Columbus Day by the White House, one national organization, the Order Sons and Daughters of Italy in America, described the holiday as representing “not only the accomplishments and contributions of Italian Americans, but also the indelible spirit of risk, sacrifice and self- reliance of a great Italian icon that defines the United States of America.”

Organization officials did not respond to requests for comment.

At a Southampton school board meeting in 2019 where attendees discussed observance of Columbus Day, Lou Gallo, a Sons of Italy member from Miller Place, said critics of Columbus resorted to “gross exaggeration, misinformation, disinformation, faulty interpretations, faulty translations, textural corruptions and non sequiturs, all to malign this man.”

A parade float travels up Fifth Avenue at the 78th annual Columbus Day Parade in 2022 in New York. Credit: Louis Lanzano

Are there guidelines on teaching the history of the holidays?

Through much of the 20th century, American textbooks tended to refer to the “discovery” of America by Europeans, said Alan Singer, Hofstra University professor of teaching, learning and technology. The 1980s brought new recognition “that there already were people here,” he said.

New York State Education Department guidelines call for young elementary school students to discuss when and why national holidays such as Columbus Day are celebrated.

According to the guidelines, older elementary school, middle school and high school students learn in greater detail about the voyages Columbus and other European explorers made, the spheres of influence their nations developed in the Western Hemisphere and about the trans-Atlantic trade of goods, movement of people, and spread of ideas and diseases known as the Columbian Exchange.

High school students will investigate the population of the Americas before the arrival of the Europeans, evaluating the impact on indigenous populations, the guidelines say.

How do teachers blend the two perspectives?

Generally, said Gloria Sesso, president for the Long Island Council for the Social Studies, teachers “aren’t talking about an evaluation of Columbus — we’re talking about how perspectives have changed,” emphasizing different views and different sources that show how and why those views change over time.

Several schools officials said the holidays did not lend themselves to a definitive characterization of Columbus as hero or villain.

In Uniondale, a district whose calendar observes both Columbus Day and Indigenous Peoples Day, U.S. History teacher Jillian Pallone said the lesson plan for her 11th-grade students included a history of the holidays, using sources like video interviews with advocates for each holiday to evaluate different perspectives.

“We talk about what points did each side raise, what surprised you, how do the arguments relate to the broader impact of colonization on Native Americans,” she said.

At Roosevelt schools, where the calendar observes Indigenous Peoples Day, Superintendent Shawn Wightman said in an email that the district’s adoption of the day followed state and national leaders who “emphasized the importance of honoring the resilience and contributions of Indigenous peoples while also recognizing the need to reflect on the more complex legacy of colonization.”

Roosevelt educators engage “students in discussions that explore the complexities of Columbus’ voyages, including both the achievements and the consequences of his expeditions, particularly the impact on Indigenous communities. We emphasize the importance of acknowledging these historical truths while encouraging students to reflect on the broader implications of how history is told and who gets to tell it.”

Fatima Morrell, Southampton schools superintendent, said educators there, partly because of the district’s Shinnecock population, have for years tried to emphasize the experience of Indigenous peoples in their teaching.

“There were civilizations and economies and systems of knowledge of ways of knowing” in the Western Hemisphere before the Europeans arrived, and teachers encourage students to use a variety of primary and secondary sources to investigate them, she said.

The district’s calendar decision was controversial, she said, but “when we elevate indigenous history and culture, it doesn’t mean we’re diminishing Italian American history and culture.”

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=670b98c3e1ca4c95a55773c5a0c19ea3&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.newsday.com%2Flong-island%2Feducation%2Fcolumbus-indigenous-peoples-long-island-schools-native-american-w676fah9&c=2132038701041165550&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-10-12 21:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.