Despite the blinding summer sun, the temperatures would have been around -20C as Gabriel Boric, ChileŌĆÖs president, made his historic visit to the South Pole last week.

To mark the occasion, the millennial briefly took his hat and gloves off to pose for photos beside a Black Hawk helicopter after making the arduous 24-hour journey from Santiago.

Mr Boric is thought to be the first sitting head of government from the Americas to reach the South Pole. He was accompanied by his environment and defence ministers, the three heads of ChileŌĆÖs armed forces and a scientific delegation.

Their presence, he said, showed ChileŌĆÖs deep commitment to Antarctica remaining a ŌĆ£continent of science and peace.ŌĆØ

Officially, the trip was to promote the environmental agenda of Mr Boric, a leftist leader who has been outspoken on climate change. He specifically mentioned the monitoring of particles of black carbon (soot) settling on the ice and subtly undermining its ability to reflect ŌĆō rather than absorb ŌĆō the sunŌĆÖs rays.

Chile is one of the 12 original signatories of Antarctic Treaty which is designed to keep the continent a region of ŌĆśscience and peaceŌĆÖ – Marcelo Segura/AFP

The president, 38, said: ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs also confirmation of our claim to sovereignty in this space. From here, everything is north. There are only 12 flags flying here. One of them is Chilean and that is a source of pride for us.ŌĆØ

He was referring to the original 12 signatory nations of the Antarctic Treaty, which came into effect in 1961. They include the United Kingdom, United States and Russia.

The treaty stipulates that any activities below 60 degrees south, in other words the entire Antarctic continent, must be both scientific and peaceful.

Over the years, the accord has effectively put into deep freeze various nationsŌĆÖ territorial claims on the region and bars mining, fishing and other commercial activities.

The Antarctic Treaty also prevents the militarisation of the only landmass on Earth which is not divided into nation states.

In doing so, it has preempted the geopolitical tensions now gathering pace at the other icy end of the planet, in the Arctic, which has no equivalent international protocol.

There, Russia, which now even has an Arctic land border with Nato, has long been aggressively asserting its supposed hegemony in the region.

Russian navy submersibles even planted a rust-proof titanium Russian flag on the seabed three miles below the North Pole in 2007.

Yet AntarcticaŌĆÖs uneasy peace is increasingly skating on thin ice, which is probably what prompted Mr BoricŌĆÖs visit.

China, Russia and even Iran have in recent years been testing the limits of the Antarctic Treaty and jockeying for position to access the regionŌĆÖs vast reserves of oil, gas and minerals as well as its rich fisheries, should the agreement break down.

AntarcticaŌĆÖs uneasy peace is increasingly skating on thin ice, which is probably what prompted Gabriel BoricŌĆÖs visit – Presidential Palace/Reuters

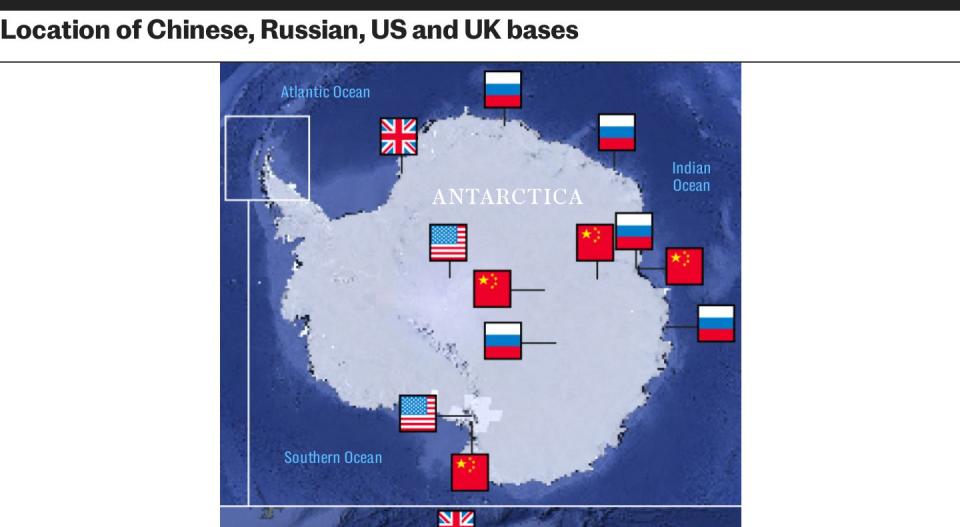

Although the Antarctic Treaty prohibits defence activities, most countries with a footprint in the region rely on their armed forces for the complex, burdensome logistics of maintaining bases in such a remote, inhospitable location.

Beijing, Moscow and others are suspected of using that loophole to set up facilities that are ostensibly research stations but may also be military listening posts, taking advantage of the AntarcticŌĆÖs clear, open skies.

China, meanwhile, regularly sends its long-range fishing fleet to hoover up krill in the southern seas, claiming it is for scientific research. Russian vessels have been accused of falsifying their location data, presumably as they fish in prohibited Antarctic waters.

In 2021, Moscow and Beijing banded together to veto a proposal from Argentina and Chile to declare a new marine reserve ŌĆō a reserve that would complicate any attempts to fish there should the Antarctic Treaty break down.

Beijing is now building its first nuclear icebreaker. That would make it only the second country to develop this technology, after Russia. The United StatesŌĆÖ two icebreakers, both diesel-powered, are ageing and increasingly unreliable.

China has also just built its fifth research station on the continent. Beijing, which has a strategy of ŌĆ£civil-military fusionŌĆØ for all state-funded scientific research, did so without sharing its plans for the base, as required by the Treaty.

More unexpectedly, Iran announced in 2023 its plans to build a permanent base on the icy continent. Admiral Shahram Irani, the commander of the Iranian navy, even claimed that Tehran had ŌĆ£property rightsŌĆØ in Antarctica.

Little wonder then the nagging worry of Mr Boric and other democratic leaders about the Antarctic ambitions of various adversaries of the West.

Growing concerns have not been eased by a provision established by the Antarctic Treaty that allowed nations to carry out surprise inspections of each otherŌĆÖs facilities as a means of enforcing the demilitarisation provisions of the Treaty.

ŌĆ£Some of the concern is being driven by factors elsewhere in the world, like RussiaŌĆÖs invasion of Ukraine,ŌĆØ says Bill Muntean, a former US diplomat who has led some of those surprise inspections. ŌĆ£It has upended international norms and is having repercussions in Antarctica.ŌĆØ

Before Mr Boric, only two other heads of government, the prime ministers of New Zealand and Norway, had ever visited the South Pole.

In an unstable world, with a growing population and gathering resource scarcity, he may well not be the last.

Broaden your horizons with award-winning British journalism. Try The Telegraph free for 1 month with unlimited access to our award-winning website, exclusive app, money-saving offers and more.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=678592255c4c4b5bb5c64cbe6218429d&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.yahoo.com%2Fnews%2Fchile-president-makes-groundbreaking-visit-070300549.html&c=17681862975546897728&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2025-01-11 18:03:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.