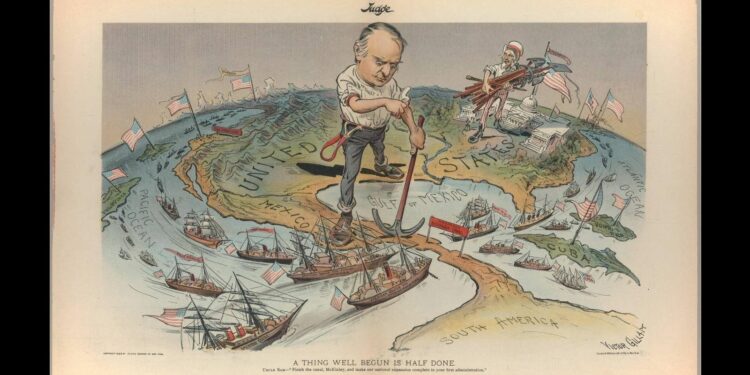

The mysterious explosion of a US Naval ship in Havana harbor in February 1898 was followed by accusations of Spanish mines and the slogan тАЬRemember the Maine!тАЭ McKinley sent America to war. The Spanish colonies of Guam, Cuba, and Puerto Rico fell like overripe fruit into the basket of American empire.

US Commodore George Dewey sailed to Manila Bay at the outbreak of the war. His defeat of the dilapidated and aged Spanish fleet, in which one American sailor died of heatstroke, was hailed a great victory in Washington. Within a month, books were being published in the United States entitled: тАЬOur New Possessions. Eldorado of the Orient.тАЭ

Rosa Luxemburg in Reform or Revolution, her masterful polemic against revisionism published in 1900, wrote of тАЬtwo extremely important phenomena of contemporary social life: on the one hand, the policy of tariff barriers, and on the other, militarism.тАЭ She explained the role of tariffs in the era of McKinley: тАЬ[A] protectionist tariff on any commodity necessarily results in raising the cost of production of other commodities inside the country. It therefore impedes industrial development. But this is not so from the viewpoint of the interests of the capitalist class. While industry does not need tariff barriers for its development, the entrepreneurs need tariffs to protect their markets. This signifies that at present tariffs no longer serve as a means of protecting a developing capitalist section against a more advanced section. They are now the arm used by one national group of capitalists against another group.тАЭ

MilitarismтАФimperialist warтАФwas the inevitable outgrowth of this economic warfare. It was on the basis of this logic that in May 1898, Senators Henry Cabot Lodge and Stephen Elkins visited McKinley and urged him to turn the Philippines into a US colony. The Boston Evening Transcript published the substance of their remarks to the President:

You have stood for the great American doctrine of protection to American industries, thus insuring the possession of the home market for our manufactures. So far so good. But the time has now come when this market is not enough for our teeming industries, and the great demand of the day is an outlet for our products. We cannot secure that outlet from other protective countries, for they are committed to the same policy of exclusion that we are, so our only chance is to extend our American market by acquiring more trade territory. With our protective tariff wall around the Philippine Islands, its ten million inhabitants, as they advance in civilization, would have to buy our goods, and we should have so much additional market for our home manufactures. As a natural and logical sequence of the protective system, if for no other reason, we should now, acquire these islands and whatever other outlying territories seem desirable.

These were the economic motives of US imperialism: to seize from its rivals as large a sphere of economic control for American capitalism as possible. This drive was focused above all on China. Sen. Albert Beveridge in a speech to the legislature in January 1900, with the war of conquest in the Philippines less than a year old, made explicit the aims of US imperialism in Asia. It remains relevant, for while the data have changed, the motive has not; it is worth quoting at length.

Mr President, the times call for candor. The Philippines are ours forever, тАЬterritory belonging to the United States,тАЭ as the Constitution calls them. And just beyond the Philippines are ChinaтАЩs illimitable markets. We will not retreat from either. We will not repudiate our duty in the archipelago. We will not abandon our opportunity in the Orient. We will not renounce our part in the mission of our race, trustee, under God, of the civilization of the world. тАж

Our largest trade henceforth must be with Asia. The Pacific is our ocean. More and more Europe will manufacture the most it needs, secure from its colonies the most it consumes. Where shall we turn for consumers of our surplus? Geography answers the question. China is our natural customer. She is nearer to us than to England, Germany, or Russia, the commercial powers of the present and the future. They have moved nearer to China by securing permanent bases on her borders. The Philippines give us a base at the door of all the East. . . .

ChinaтАЩs trade is the mightiest commercial fact in our future. Her foreign commerce was $285,738,300 in 1897, of which we, her neighbor, had less than 9 percent, of which only little more than half was merchandise sold to China by us. We ought to have 50 percent, and we will. And ChinaтАЩs foreign commerce is only beginning. Her resources, her possibilities, her wants, all are undeveloped. She has only 340 miles of railway. I have seen trains loaded with natives and all the activities of modern life already appearing along the line. But she needs, and in fifty years will have, 20,000 miles of railway. Who can estimate her commerce then?

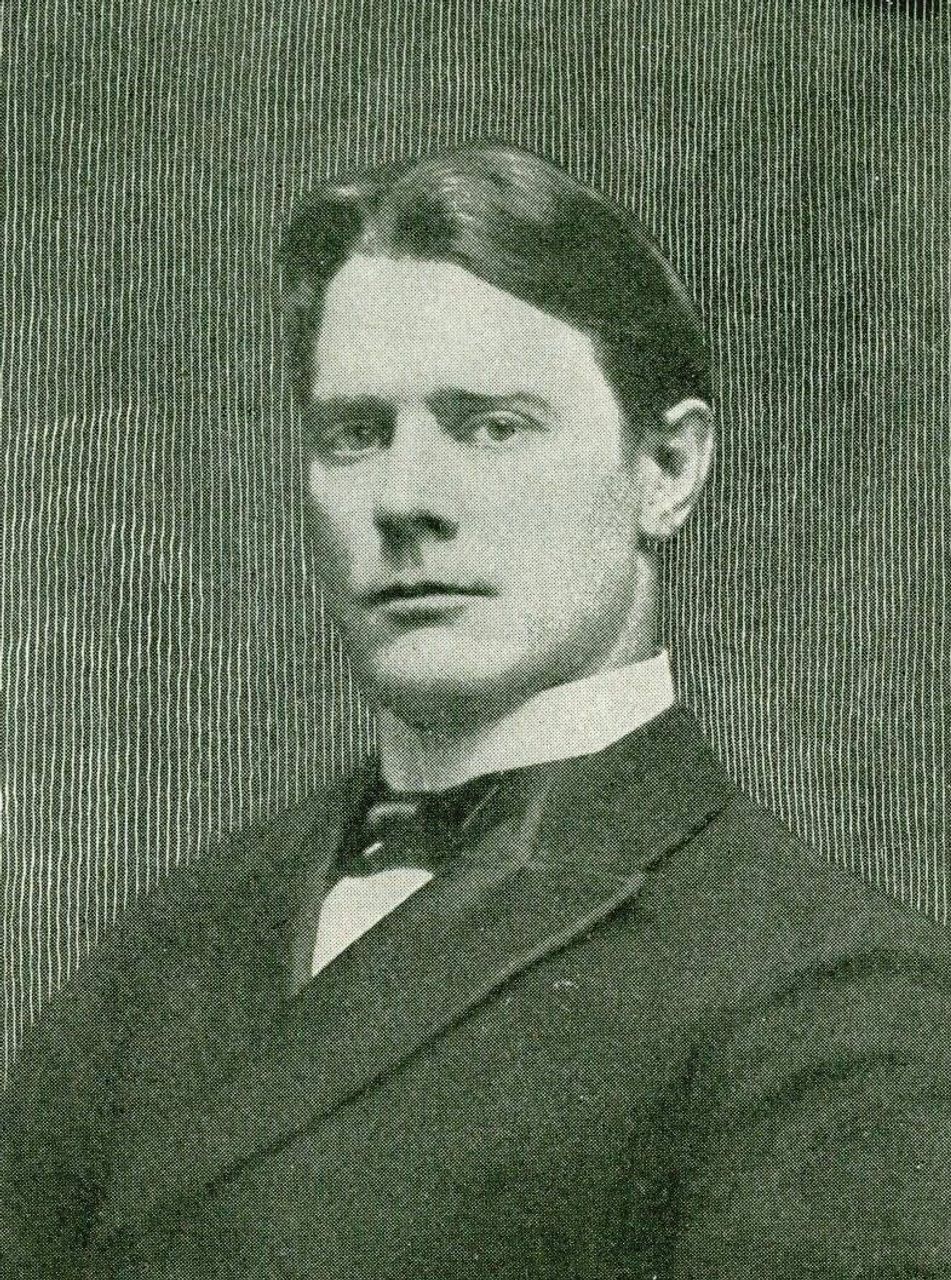

Albert Beveridge

Albert Beveridge

From the inception of US empire, the Philippines was conceived of by the United States as its foothold for control of Asia, and above all the vast markets of China, against rival imperialist powers. But while these were actual engines of empire, McKinley justified AmericaтАЩs colonial enterprise in Asia in the language of racist paternalism and evangelical Christianity. Speaking to a delegation of Methodist church leaders in November 1899, McKinley spun his decision to conquer the Philippines:

When I next realized that the Philippines had dropped into our laps I confess I did not know what to do with them. тАж I walked the floor of the White House night after night until midnight; and┬аI am not ashamed to tell you, gentlemen, that I went down on my knees┬аand┬аprayed Almighty God for light and guidance more than one night.┬аAnd one night late it came to me this wayтАФI donтАЩt know how it was, but it came:┬а(1)┬аThat we could not give them back to SpainтАФthat would be cowardly and dishonorable;┬а(2) that we could not turn them over to France and GermanyтАФour commercial rivals in the OrientтАФthat would be bad business and discreditable;┬а(3)┬аthat we could not leave them to themselvesтАФthey were unfit for self-governmentтАФand they would soon have anarchy and misrule over there┬аworse than SpainтАЩs was; and (4)┬аthat there was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and┬аto educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them,┬аand by GodтАЩs grace do the very best we could by them, as our fellow-men for whom Christ also died.┬аAnd then I went to bed, and went to sleep, and slept soundly,┬аand the next morning I sent for the chief engineer of the War Department (our map-maker), and I told him to put the Philippines on the map of the United StatesтАж

This policy of conquest, pinning the Philippines to the map of the United States, McKinley termed тАЬbenevolent assimilation.тАЭ

The Philippine Republic

It was not the guns of DeweyтАЩs fleet, but two years of bitter fighting by Filipino revolutionaries that won the Philippines independence from Spain. When the Americans arrived, the Spanish forces had retreated to within the walled city of Intramuros in Manila, surrounded by the forces of the revolution. The Spaniards signaled to Dewey that they would surrender, but not to the Filipinos. The Americans and Spanish, ostensibly at war, met and secretly arranged to stage a mock battle for control of Manila, transferring control of the walled city from a dying colonial to a rising imperialist power. They had a common enemy: the population outside the walls.

Emilio Aguinaldo in military uniform

Emilio Aguinaldo in military uniform

Under the leadership of Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo, the Filipinos proclaimed their independence from Spain on June 12, 1898. Drawing heavily on the American Declaration of Independence, the assembled Filipinos declared:

That they are and have the right to be free and independent; that they have ceased to have any allegiance to the Crown of Spain; that all political ties between them are and should be completely severed and annulled; and that, like other free and independent States, they enjoy the full power to make War and Peace, conclude commercial treaties, enter into alliances, regulate commerce, and do all other acts and things which an Independent State has a right to do,

And imbued with firm confidence in Divine Providence, we hereby mutually bind ourselves to support this Declaration with our lives, our fortunes, and with our most sacred possession, our Honor.

Aware of the discussion in the United States that the Philippines was a new possession, and that the justification for this was the FilipinosтАЩ supposed тАЬunfitnessтАЭ for self-government, the revolutionaries rapidly set about drawing up a constitution and setting up the administrative apparatus of the new Philippine Republic. At the center of these efforts was a man named Apolinario Mabini. The son of an impoverished peasant family, Mabini had by dint of extraordinary effort worked his way through university and become a lawyer. He was fluent in multiple languages and became the intellectual guiding force of the Philippine revolution. Inspired by the American and French revolutions, he was a man of science and the secular Enlightenment. He was stricken by polio in his twenties, paralyzed from the waist down, and had to be carried in a hammock from battlefield to battlefield during the war with the Americans. Captured, he refused to swear allegiance to Washington and was exiled to Guam.

Apolinario Mabini

Apolinario Mabini

The Constitution of the Republic granted universal male suffrage, made state-funded public education through high school mandatory for all Filipinos, contained a clause explicitly separating Church and State, and enshrined the principle of birthright citizenship. Anyone born to a Filipino parent, or born in the Philippines, or naturalized in the Philippines was a citizen. The revolutionaries declared that they were confiscating the vast landholdings of the Catholic church for public use.

The American conquerors tore up the constitution of the Republic, imposed the Chinese Exclusion Act of the United States on their new colony, and when, in 1935, they finally granted their colony a constitution, they made citizenship a matter of race. That definition stands to this day and has excluded generations of immigrants from citizenship, most particularly the vulnerable population of Chinese Filipinos. In 1906 the United States returned to the Roman Catholic church all lands confiscated by the revolutionaries.

Benevolent Assimilation

These self-governing people, тАЬunfit for self-government,тАЭ were purchased by the United States from Spain with the Treaty of Paris on December 10, 1898, for the sum of $20 million. Not a bad price; the United States bought itself a colony for a little less than $3 a head. The treaty went before the US Senate for ratification. The deadline for a vote was February 6 and it was uncertain if McKinley could swing the needed vote of a two-thirds majority.

Tensions between the armed patrols of American forces within Manila and the Philippine forces surrounding them were razor sharp. On the night of February 4, an American sentry fired on a Filipino sentry and conflict erupted. The Americans burst out of Manila overwhelming the Filipino lines, bombarding their trenches with repeating rifle and artillery fire. Dewey sailed up the Pasig river and pounded the trenches with shells. The outbreak of the war secured the approval of McKinleyтАЩs treaty in the Senate a day later by a margin of one vote.

It proved a peculiarly American war, dealing death, mayhem and catastrophe on the population in the name of тАЬhuman rightsтАЭ and тАЬdemocracy.тАЭ Mass murder and imperialist plunder were committed with protestations of the noblest intentions.

The Filipino forces, many barefoot and poorly armed, fought with immense courage. Motivated by political ideals and the desire to be free, they cited the American declaration of independenceтАФthat all men are created equalтАФand they were shot down by US troops.

Filipino dead in the portion of the trenches on February 5, 1899, the first day of the war. [Photo: US National Archive]

Filipino dead in the portion of the trenches on February 5, 1899, the first day of the war. [Photo: US National Archive]

The early months of the war were a grotesquely lopsided struggle. US forces were armed with Krag bolt-action rifles, Filipino troops often only with bolos. The trenches of the Filipino forces were scenes of carnage. The corpses of the valiant defenders of the republic were left to rot.

What quickly became apparent to the American commanders was that the political sympathies of almost everyone they sought to colonize lay with the revolutionary troops and the Republic. Gen. Arthur MacArthur, who became commander of the US forces in the war and who was the father of Douglas MacArthur, wrote of тАЬthe almost complete unity of action of the entire native population.тАЭ

McKinley ordered more troops to the Philippines, then yet more. By 1900, 70,000 US troops occupied a nation at war to keep its freedom. Gen. Aguinaldo, president of the Republic, commanded the Philippine army, adopting a strategy of guerrilla warfare. Historian Luzviminda Francisco, in an article entitled тАЬThe First Vietnam,тАЭ wrote that тАЬLack of firearms indeed continued to be the single most pressing issue for the Filipinos.тАЭ She estimated that тАЬonly one partisan in four was actually armed.тАЭ

The Americans declared the Filipino combatants тАЬbandits,тАЭ who were not to be accorded the rights of prisoners of war, and turned to the tools of counter-insurgency: torture, the reconcentration of large populations, and the execution of prisoners.

US soldiers administer the тАЬwater cureтАЭ torture [Photo: UN National Archive]

US soldiers administer the тАЬwater cureтАЭ torture [Photo: UN National Archive]

American troops interrogated Filipinos with a form of torture they adopted from the Spanish, the тАЬwater cure.тАЭ They forced prisoners, both soldiers and civilians, to drink gallons of water and then trampled on their swollen abdomens. Many prisoners died of burst innards.

American naval vessels shelled coastal communities; the US Army burned villages to the ground. The populations of entire islands were ordered into concentration camps, a policy known as reconcentrado.

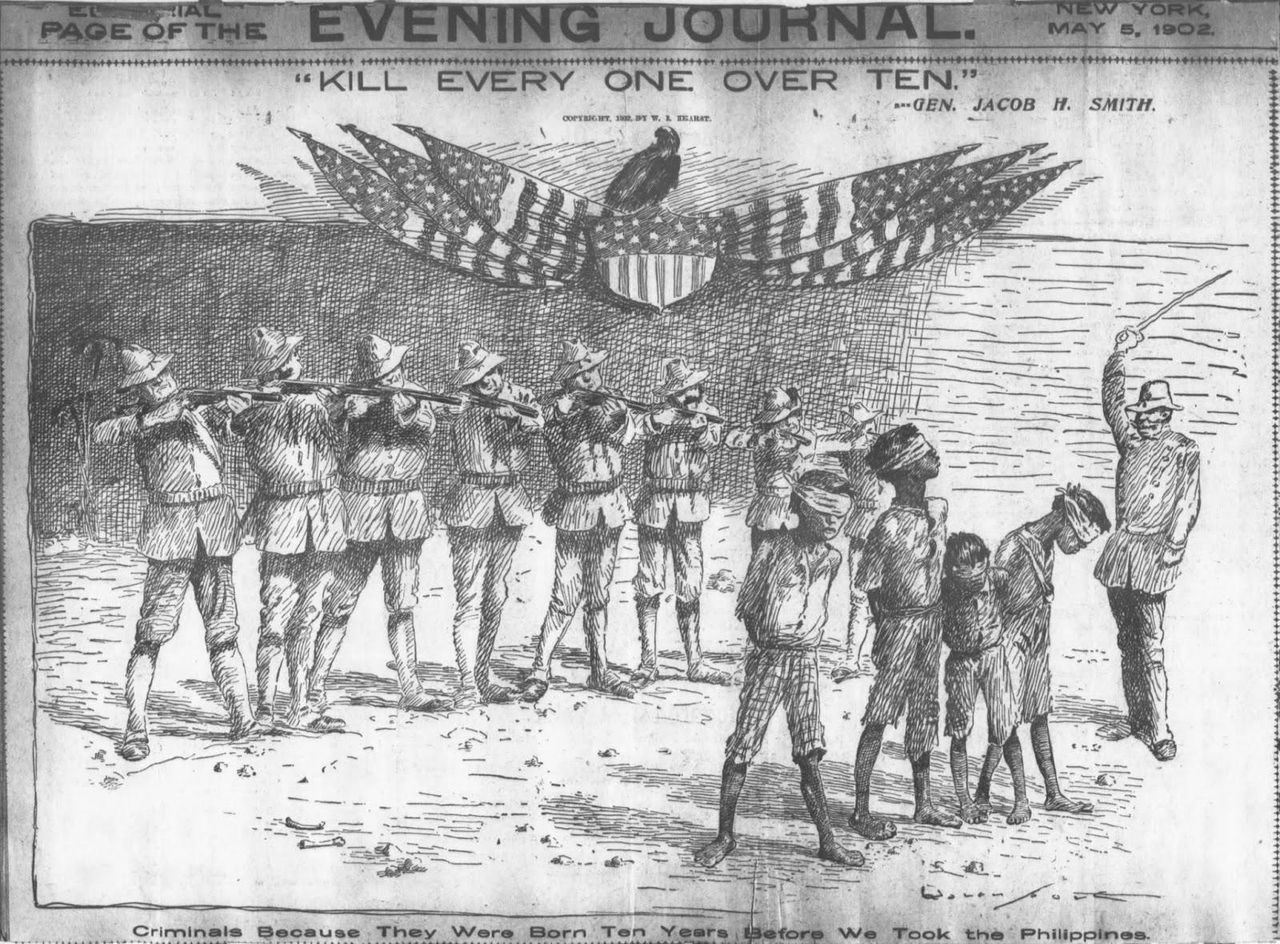

Angered at the death of 54 American soldiers in an ambush, General Jacob Smith told his troops in the province of Samar тАЬI want you to kill and burn, the more you kill and burn the more you will please me тАж make Samar a howling wilderness.тАЭ When asked to set an age limit for killing, he answered, тАЬEveryone over ten.тАЭ All of the inhabitants of Samar, a population of over 250,000 people, were relocated to concentration camps. Those outside the camps were killed. Smith was brought before a US court-martial to stand trial for his orders. He was found guilty of тАЬconduct to the prejudice of good order,тАЭ sentenced to be тАЬadmonished,тАЭ and quietly retired.

Front page of the New York Evening Journal, 5 May 1902: тАЬKill Everyone over Ten.тАЭ Note that the bald eagle has been replaced by a vulture.

Front page of the New York Evening Journal, 5 May 1902: тАЬKill Everyone over Ten.тАЭ Note that the bald eagle has been replaced by a vulture.

The people of the provinces of Batangas, Marinduque, Albay, and elsewhere, were also forced into concentration camps. The area outside the camps was known as the тАЬdead lineтАЭ and any Filipino outside it would be shot on sight. Agricultural production came to a standstill. In Batangas, Gen Franklin Bell ordered all property outside the dead line put to the torch. Francisco recorded that, тАЬAccording to statistics compiled by US Government officials, by the time Bell was finished at least 100,000 people had been killed or died in Batangas alone as a direct result of the scorched-earth policies, and the enormous dent in the population of the province (which was reduced by a third) is reflected in the census figures.тАЭ

The reconcentrated population, tens of thousands of men, women and children crowded together in a wasteland of makeshift huts, had no access to sanitation, adequate nutrition or medical care. An incalculable number, well over 100,000, died of cholera, typhoid, dysentery, beriberi, and malaria as a direct result. Malnutrition turned to starvation; surviving historical photographs of gaunt, slat-ribbed Filipinos in American concentration camps serve as visible evidence.

The US War Department censored press dispatches, keeping the American public in the dark about the war waged in their name. At home, Thomas Edison used his recently developed film studio in New Jersey to produce war propaganda reels for the government. The US population eventually learned of the reality of the conduct of the war from letters sent home by soldiers.

In the United States, opposition to the war was organized in the Anti-Imperialist League. In his monumental 1916 work, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, Lenin aptly characterized the League as тАЬthe last of the Mohicans of bourgeois democracy,тАЭ but stated that as long as their criticism тАЬshrank from recognising the inseverable bond between imperialism and the trusts, and, therefore, between imperialism and the foundations of capitalism, while it shrank from joining the forces engendered by large-scale capitalism and its development, it remained a тАШpious wish.тАЩтАЭ

The most eloquent of American critics of American imperialism was Mark Twain. He wrote of the impact of empire on democracy in the United States:

It was impossible to save the Great Republic. She was rotten to the heart. Lust of conquest had long ago done its work. Trampling upon the helpless abroad had taught her, by a natural process, to endure with apathy the like at home; multitudes who had applauded the crushing of other peopleтАЩs liberties, lived to suffer for their mistake in their own persons. The government was irrevocably in the hands of the prodigiously rich and their hangers-on, the suffrage was become a mere machine, which they used as they chose. There was no principle but commercialism, no patriotism but of the pocket.

Imperialism, in the precise phrase of Lenin, is тАЬreaction down the line.тАЭ The apparatus designed by US imperialism for the coercion, surveillance, and policing of the colonized Filipinos was quickly redeployed within the United States against the labor movement and political radicals and revolutionaries, as historian Alfred McCoy extensively documented in his work, Policing AmericaтАЩs Empire. Col. Ralph van Deman, head of Army intelligence in the Philippines, was made head of the Military Intelligence Division in the United States responsible for surveilling the American population for suspected sedition under the Espionage Act of 1917. He created the vast vigilante network of domestic informers and spies in the American Protection League. He is but one example among thousands of тАЬreaction down the line.тАЭ

Aguinaldo was captured in March 1901. Six months later, McKinley was тАЬbenevolently assimilatedтАЭ by an anarchistтАЩs bullet. Theodore Roosevelt became president of the United States. On July 4, 1902, he declared the war in the Philippines over. Guerrilla fighting continued over the course of nearly a decade, led by such figures as Gen Miguel Malvar and Gen Macario Sakay.

Bud Dajo massacre, 1906 [Photo: US National Archives]

Bud Dajo massacre, 1906 [Photo: US National Archives]

1906 found US troops still actively reconcentrating and waging war on the people of the southern island of Mindanao. In March, an entire village fled before advancing US troops, seeking shelter in the crater of a nearby dormant volcano known as Bud Dajo. With repeating rifles, Gatling guns and heavy artillery, the American troops opened fire from the rim of the volcano on the defenseless villagers huddled below. Of the estimated 1,000 men, women, and children who sheltered in the crater, six survived. Their corpses were piled five feet high. President Roosevelt wired his congratulations to the commanding American General.

Donald Trump is not unfamiliar with the bloodshed of the Philippine-American War. In a fascistic speech delivered in 2016, he cited with immense enthusiasm an apocryphal story of how Gen Pershing finally subdued Mindanao by executing Muslim prisoners with bullets dipped in pigтАЩs blood.

How many Filipinos died as a result of the American war of occupation? The most conservative estimate is 200,000, a figure that is certainly too small. Gen. Bell, who commanded the concentration camp policy in Batangas, estimated to the New York Times a death toll of 600,000 on the island of Luzon. A figure for the entire Philippines that begins to approach 1 million is likely near to the truth.

Conclusion

On the bones of the Filipino dead, Washington built its тАЬshowcase of democracy in Asia.тАЭ The showcase has served ever since as the staging ground for US imperialism in Asia. In 1900, it was from the Philippines that the United States intervened in crushing the Boxer Rebellion and joined in the imperialist carve-up of China. It was from the Philippines that in the 1950s Washington staged a secret and illegal bombing campaign against Indonesia. A decade later, US military bases in the Philippines serviced the carpet bombing of Vietnam and Cambodia. The early US advisors in Vietnam, the CIA operatives who laid the foundation for WashingtonтАЩs bloody, protracted imperialist war, all were trained in the Philippines. The relationship continues to this day. Last year, the United States deployed the intermediate range Typhon missile launcher system to the northern Philippines with the capacity to target all of China.

Washington sustained its тАЬshowcaseтАЭ with espionage and imperialist machinations, selecting and deposing presidents. When US interests could no longer be preserved through the trappings of democracy, Washington funded and endorsed the brutal dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos.

The Philippine-American War is little remembered in either the Philippines or the United States. The US government termed the entire bloody affair an тАЬinsurrection.тАЭ The Filipinos had been purchased for $20 million. They were in rebellion against the duly constituted government of the United States. To this day, many of the documents of the Philippine Republic are kept in the US National Archives under the label тАЬPhilippine Insurrection.тАЭ

The victorious American colonizers wrote the first history textbooks for the Philippine public school system, and the conquerors became тАЬliberators.тАЭ American capital flooded the colonial economy, seeking profit. The capital city still bears the colonial imprint. Taft Avenue runs through Manila, and the rich reside in Forbes Park. The US president and ambassador will invariably speak, in tones of condescension, of the countriesтАЩ historic ties. They are ties that were forged with bloodshed.

This is what is invoked when Trump speaks of his admiration for McKinley. He is expressing his desireтАФthe desire of the rapacious American oligarchyтАФto return to open colonial rule and the conquest and annexation of territories. His insistent enthusiasm for McKinley must be taken as a warning.

The parallels to the present are striking: economic warfare and territorial annexation to secure for American capitalism control over markets for investment and exploitation. Now as then, China is the fixation of Washington, not merely as a threat to American global economic dominance but also as a prize to be carved up, a land whose vast wealth can be pillaged, with a labor force a billion strong waiting to be exploited. TrumpтАЩs moves to annex Greenland, to seize Panama, to take Canada, express the same fundamental logic as McKinleyтАЩs seizure of the Philippines: He seeks a staging ground for war with China.

But while the logic of imperialist expansion is inexorable in its continuity, a century and a quarter have passed, and the world has been qualitatively and fundamentally altered.

The wealth of the oligarchs has grown beyond the wildest fantasies of the robber barons from the era of McKinley. In 1909, the Sugar Trust, an economic and political behemoth, had a capital of $90 million, a bit over $3 billion in 2025 dollars. Today, one man, Elon Musk, has an estimated wealth of slightly less than $400 billion dollars. This is more than a change in magnitude. The modern oligarchy sits atop a mountain built of over a centuryтАЩs compound interest in human misery, class exploitation and imperialist plunder. They have been schooled in rapine and will allow nothing, not even nuclear destruction, to stand in the way of profit.

As in the era of McKinley, imperialist war is twin to the repression of the working class. But again, the scale now is far more vast, surveillance insinuated into every aspect of social life, the capacity for censorship expanded to a degree unimaginable. Where McKinley and his successors undermined and carved away at civil liberties and democratic rights, Trump seeks to scrap them entirely.

There is a final difference, and it is decisive. McKinley expressed the ambitions of US empire on the rise; Trump, the desperation of its decline. McKinleyтАЩs tawdry democratic pretenses have been thrown aside. Trump presents the world with the openly fascist face of American empire.

We are no longer in the age of the Anti-Imperialist League, however, of opposition to colonialism as a тАЬpious wish.тАЭ The twentieth century revealed, above all in the October revolution of 1917, the only viable method of anti-imperialist struggle: the international solidarity and mobilization of the working class for the overthrow of capitalism.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=67b6c9cd54844072a825a514759c78e4&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.wsws.org%2Fen%2Farticles%2F2025%2F02%2F20%2Fwpip-f20.html&c=6099621402155687070&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2025-02-19 16:07:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.