Fidel Castro |

Article

Views on Cuba

There are almost as many views about Cuba’s past, present and future as there are individuals. Whether you were born in Cuba, have traveled there, or just learned something about the island’s complex history, chances are you have an opinion about what Fidel Castro has meant to the Cuban nation and the Cuban people.

Read interview escerpts from a distinguished group of experts presenting four divergent perspectives.

An Exploration into the Origins of the Cuban Human Rights Movement

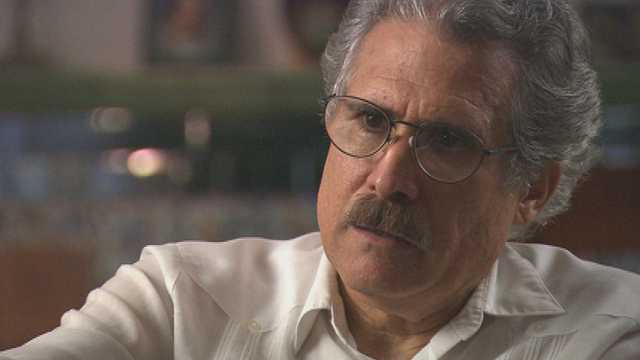

The president of the Miami-based Cuban Committee for Human Rights, Ricardo Bofill spent 12 years imprisoned in Cuba.

Ricardo Bofill

Conventional wisdom has it that when Fidel Castro departs the scene — an event which is bound to occur sooner rather than later — Cuba and Cubans will have a chance to start all over again. For some, this means a chance to leave the island altogether and join their relatives or former countrymen in Miami. For elements of the exile community in Southern Florida it means, presumably, a chance to turn the clock back to 1958, when the island was a close ally of the United States and had one of the highest standards of living in Latin America. For others, it means important political and economic changes which will turn the island into a “bourgeois democracy” similar to Costa Rica, El Salvador or the Dominican Republic. For still others, it means a chance to finally make socialism work, in the sense that in the absence of a U.S. embargo (and U.S. political and diplomatic hostility) the country would presumably have a chance to fully realize its economic potential within the existing Communist system.

Evidently those who dream these dreams are not the same people; in some cases they do not even occupy the same political jurisdiction. The official policy of the United States government under every administration since President John F. Kennedy has been the third option — to see Cuba transformed into an “ordinary” Latin American democracy. To be sure, no administration, including the present one, has the slightest idea exactly how such an eventuality can be brought about; even the recent Powell report is largely devoted to U.S. responses after a transition has begun. The last option — which implies the lifting of the embargo and the normalization of relations — has been the official preference of the Cuban government from the very beginning, although there is reason to doubt that Fidel Castro himself sincerely favors it as much as many of the people around him.

For its part, the exile community dreams dreams that can probably never be realized — to return home both physically and spiritually, to vindicate its opposition to the revolution, to exact revenge from those under whose rule they and their families have suffered enormously, to merge the Cuba of the island with the Cuba of the diaspora. For people on the island, the issue of the day is more basic — economic survival in a system which is deliberately organized to produce scarcity for purposes of political control. Ordinary Cubans are tired of long lines to buy basic necessities, of the endless indoctrination, of calls for ceaseless sacrifice, of promises of a well-being that continually recede behind the horizon. But they also harbor a deep fear of a sudden political upheaval which would plunge the country into a sea of uncertainty. These fears are not without foundation. Quite apart from revanchist fantasies of some elements of the exile community, it is far from clear that an alternative system will produce abundance, all the more so since Cuba has lost its place in the world sugar market and is unlikely to ever again be a prosperous country.

Nobody can forecast exactly what political form Cuba will assume after Fidel Castro has passed from the scene. But some predictions can be made with reasonable certainty. There will be no civil war or political uprising, partly because those who might be inclined to participate in such an event have already left the island (or are planning to leave), partly because the military and police remain the most effective agencies of the government, and partly, too, because the suffocating mechanisms of an authoritarian state assure that any potential opposition is divided and infiltrated. Nor will there be a succession crisis, since the dictator has already made clear that his brother Raúl will become head of state in the event of his disappearance. Should Raúl Castro die before his brother, doubtless another successor would be named, possibly even one of Fidel Castro’s sons, two of whom have recently been profiled in the Cuban media.

It is less clear, however, what the real political and economic content of Cuba will be under Raúl Castro or some other member of the Castro family. A kind of crony capitalism, in conjunction with unscrupulous foreign investors, is already growing within the larger (and increasingly empty) shell of socialism. In many ways the country is already transitioning toward something resembling the more old-fashioned patrimonial systems such as we have seen in Trujillo’s Dominican Republic or Somoza’s Nicaragua — where the army is the most important (really, the only real) political party, and where there is a confusion of the interests of the ruling family and those of the state. Whether its leaders chose to call such a system “Marxism-Leninism,” “Communism,” “socialism” or something else is almost irrelevant.

There is a tragic fact which Cubans on both sides of the Florida straits must face. Nearly fifty years of revolution has created an enormous gap in culture, expectations, and sense of nationhood. The Cubans in the United States are destined to become like the rest of us, and over time our history will become theirs. Meanwhile, whether we or they like or not, the Cuban revolution “is” Cuban history, and cannot be unlived or forgotten. Cubans on the island cannot become North America even if they wished to do so, and Cuba can never be like the United States. In all likelihood it will always be poor and resentful of its neighbor, defiant in its attitudes and extravagant in its nationalism. At the same time, however, Cuba has no choice but to accept its fate as a Caribbean island, uniquely fitted for tropical agriculture and tourism, but little else. In that sense it is not likely to differ greatly from the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, Trinidad or a host of other places created for an eighteenth and nineteenth century world that no longer exists and can never again be summoned to life.

Future historians will marvel at the way that a revolution in a small Caribbean country known mainly for sugar, beaches and the rhumba, provoked so much passion in the United States — and the world — for half a century. The revolution in Cuba has failed to create a viable alternative to the system it replaced, and now — ironically–attributes its failures exclusively to the failure of the ex-imperial power to play its traditional role as protector, banker, and market for its harvests. Yet one might almost argue that at this point the Cuban revolution is “about” resistance to the United States and very little else. To some extent, of course, this is true of Cuban history generally (with the additional caveat that it was and is also about resistance to Spain). This, at least, would explain the long run of hostility between the two countries, and temper any optimism about the future of bilateral relations, regardless of the political system which emerges to pick up the pieces from Castro’s project.

Originally published in 2005.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66cb6b05d2f646c6899bf87080f7deb1&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.pbs.org%2Fwgbh%2Famericanexperience%2Ffeatures%2Fcastro-views-cuba%2F&c=10752054590364516696&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2017-12-30 06:15:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.