And twice now, their car has been their home, once when the family arrived in the US and again last month. After reaching their time limit at the state-run shelter where they’d been staying in Cambridge and with nowhere else to go, Alexander and his family spent four nights sleeping in the parking lot of a Somerville supermarket, his two boys huddled together in the backseat. The nights were cold, and Alexander woke up every few hours to turn on the heat.

As a recent migrant in a new land, Alexander has done what he is supposed to. He’s working. His kids go to public school. He is applying for asylum. But he has struggled to find the one thing that would offer true stability: a home.

“This,” he said, “is no life.”

After fleeing gang violence that took over his town in Ecuador, he is among 20,000-plus migrants who have come to Massachusetts in search of a better life in the past two years, only to encounter one of the worst housing shortages in the nation, a problem even many professionals here struggle to overcome.

While the state has pumped over $1 billion into its emergency shelter system to help absorb the surge of migration from Haiti and Central and South America over the last two years, that money has not changed the fundamental problem that necessitates a shelter system to begin with: There is simply not enough housing here to go around.

More than 20 migrant families who spoke with the Globe over the last few months described a desperate situation, one that many Massachusetts residents know all too well: unreachable rents for market-rate apartments, overwhelmed caseworkers, waitlists for public and affordable housing that stretch for years, even decades. Finding affordable housing means navigating a labyrinthine system that demands meticulous documentation and that has become completely overwhelmed as the number of those in shelters, or who need shelter, has ballooned. Some are lucky enough to share crowded apartments with other families they met in shelters or to rent motel rooms by the week. The unluckiest of them, including Alexander, have resorted to living out of cars, abandoned buildings, and sometimes on the street. Housing is the greatest barrier prolonging their instability.

Regulations put in place this summer by Governor Maura Healey’s administration are ratcheting up the pressure, mandating that everyone who finds themselves living in a state-run shelter — migrant or otherwise — be out within nine months. Those rules are designed to help the state cope with crushing demand and soaring bills, but social workers who help homeless families say they will force people onto the streets. It typically takes homeless families a year or more to find someplace to live once they enter shelter. These days, caseworkers sometimes only have weeks to find homes for waves of people who may be evicted from shelter soon.

Haitian migrants pulled suitcases behind them as they left the Church of the Holy Spirit in Mattapan in June, where they had spent the day. The migrants would take three trains to Boston Logan Airport, where they’d spend the night and pack up again the next morning. Erin Clark/Globe Staff

“Five years ago, we would get calls from families that were about to be homeless, and we’d always be able to find them something, some kind of shelter,” said Rachel Hand, executive director of the housing aid group Family Promise North Shore. “Now there are so many calls, so many people, we have to turn people away because we don’t have anywhere for them to go.”

Indeed, Alexander doesn’t even really know where to begin. Every listing he finds is too expensive, despite his steady job. Landlords won’t rent a studio or one-bedroom to a family of four. Some want documentation — such as a credit history — he simply doesn’t have. He does not know what affordable housing options could be available to him.

“That’s the worst thing about Boston — it’s expensive,” he said. “It’s just too much money, and I don’t know what to do.”

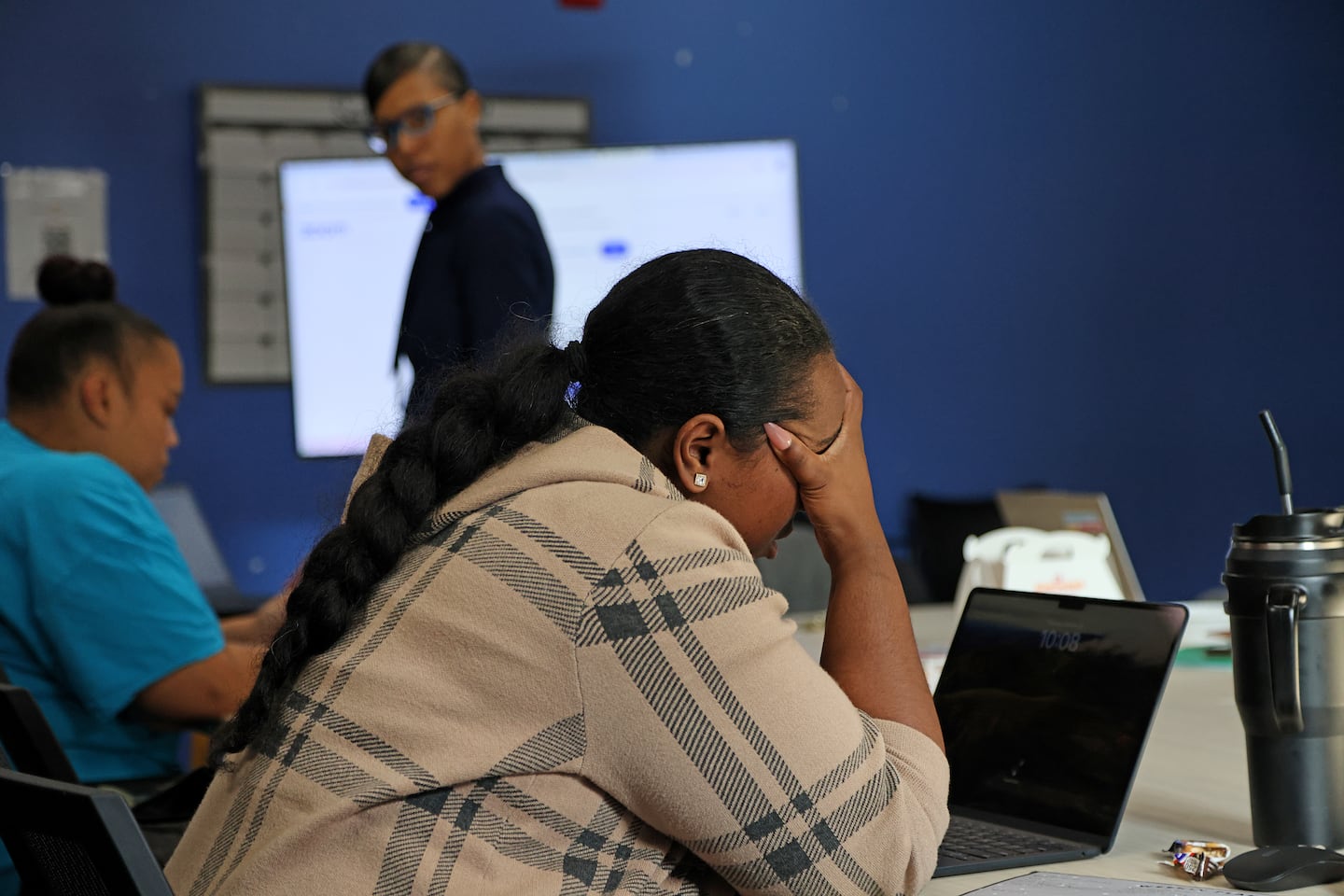

One of the front lines of this intertwined housing and migrant crisis is a conference room table on the third floor of an old brick building in Roxbury. That’s where, one recent morning, staffers at the housing nonprofit Higher Ground pored through a spreadsheet 100 rows deep. Each row represents an individual or family that is homeless, or on the verge of losing their home.

The list seems endless. One woman has been couch surfing for a year awaiting a subsidized apartment. Others are on the verge of eviction, or living in their cars or in small, overcrowded apartments. Then there are newly arrived migrants living in shelters who are about to lose their beds. Everyone on the list is stuck.

Higher Ground works with homeless Boston Public Schools families and has watched its caseload grow for years. The work is always in high demand. But these days, it can feel untenable. Two caseworkers handle 100 cases between them, and they were expecting more as the shelter restrictions kicked in.

“The system that we have been working with for all these years is at a breaking point,” said executive director Brandy Brooks. “The shelters are full of people that want a home. Unfortunately there are a lot more people looking for homes than there are homes.”

At Higher Ground, workers (from left), Candice Harding, Brandy Brooks, and Krystal Finklea discussed a family that was soon to be homeless.

At Higher Ground, workers (from left), Candice Harding, Brandy Brooks, and Krystal Finklea discussed a family that was soon to be homeless.

Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff

Even before the wave of new migrants arrived, Massachusetts was short nearly 200,000 homes for poor people in 2021, according to a report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition, and the state’s shelters were already full.

The average rent for a two-bedroom apartment in even working-class communities such as Chelsea and Lynn runs over $2,400, and more than half of the renters in the Boston area pay more rent that they can afford each month.

Traditional affordable housing is supposed to be the solution, but it is nearly impossible to access. Higher Ground is one of a few dozen small nonprofits across Massachusetts that have cropped up to try to make the system work. And that gives the organization a front-row seat when things are broken.

“Everyone kind of assumes there’s a place you can send people, and they will help you find the housing,” said Andrea Park, an advocacy director at the Massachusetts Law Reform Institute. “That doesn’t reflect reality anymore.”

Applying for a housing voucher or other resources is arduous and complex, full of bureaucratic kinks. The process is practically impossible for new arrivals to this country, who often face overwhelming language barriers and cannot access many programs without citizenship status.

Some applications require a “housing history,” a detailed paper trail of a family’s prior living situation. One incorrect detail — even something as simple as an inaccurate number or address, a single missing document, a piece of mail that doesn’t arrive on time — can be enough to disqualify someone.

“The baseline for trying to find housing as a low-income family is massive confusion about the paperwork and all of the dozens of barriers in the process,” said Isaac Simon Hodes, executive director of housing advocacy group Lynn United for Change. “You reach a point where the barriers feel too substantial to overcome.”

Sometimes the system simply doesn’t move fast enough.

That’s what happened to Daniel Montoya and Yohanna Peralta, who came to Massachusetts recently from Venezuela. Montoya has been working full time as a roofer while his wife, Peralta, has been searching for homes and taking care of their 12-year-old daughter. They have spent the last year living in a shelter in Lowell.

After months of looking, they finally found an apartment 75 miles away in Fall River. The landlord agreed to take them, but they still needed funds from a state emergency housing program, HomeBase, to close the deal. They worked with their caseworker and filled out the application, but the funds didn’t come in time, and the apartment slipped away.

“That is what makes this situation so challenging,” said Liz Alfred, an emergency shelter attorney with Greater Boston Legal Services. “It’s not just that you’re asking homeless migrants to somehow find a place to live, you’re then asking them to navigate this system that sometimes feels like it is designed to work against people.”

A lucky few have managed to find a home and put down roots.

Haitian migrant families slept outside the Wollaston MBTA stop in Quincy in August.Andrew Burke-Stevenson for The Boston Globe

Haitian migrant families slept outside the Wollaston MBTA stop in Quincy in August.Andrew Burke-Stevenson for The Boston Globe

Two months ago, Yves Lima was sleeping outside on the steps of the same Cambridge courthouse-turned-shelter where Alexander and his kids had been staying. Lima and his family, Haitians who arrived in Massachusetts earlier this year, had reached their shelter stay limit and had nowhere else to go. The Cambridge shelter was all they knew, so they slept on the hard concrete. After a couple of days, Lima heard from another family he’d met at the shelter about an apartment in Dorchester. He leapt at the chance, agreeing to share the two-bedroom and split the rent.

They got the place. It’s an informal arrangement, and it’s crowded, but it’s better than sleeping outside.

“No one wants to be here [sharing an apartment],” he said in Spanish. “If we had somewhere to go, we wouldn’t be here.”

Naturi, a single mother of two who arrived in Massachusetts roughly three years ago, is running out of time.

After nearly two years bouncing among shelters, she received notice in July that she and her two daughters —14 and 1 — would lose their spot at the end of October under the new state stay limits.

The 37-year-old from the Dominican Republic entered the shelter system in turmoil. She had been couch surfing for a year, but Naturi was pregnant, and the landlord at the Dorchester apartment where she was staying wouldn’t allow an infant to live there. The day she gave birth, she became homeless, and the next day, still recovering from a C-section, she climbed into an Uber and rode to a shelter in Concord to nurse her baby and pick up the pieces of her life again.

For two years, she has been looking for a way out. She has called the numbers on for-rent signs with the help of her 14-year-old daughter, who speaks fluent English. She has entered all the housing lotteries and is on as many waitlists as she can find. And at the suggestion of her old caseworker, she has spent days simply walking into apartment buildings and asking building managers if they have any affordable housing. None of it has worked.

Naturi said she came to the US to flee a frightening domestic violence situation that left her traumatized. Her experience in the shelter system and the fruitless search for housing have been no easier.

“Being homeless, trying to find a home for me and my daughters, has been another trauma entirely,” Naturi said in Spanish.

Naturi, who asked that her last name not be published, is working with Higher Ground and feels confident she will have somewhere to go when her time in the shelter is up.

“At a certain point, it’s not a matter of effort,” Hand said. “If you get a subsidy, it’s a matter of literal luck and timing.”

Alexander and his children slept in the car in that Somerville parking lot for four nights, until he got a call that a shelter spot had opened up for them in Holyoke. The family drove 90 miles west and moved in that night.

A few days later, Alexander’s boys, 7 and 8, raced around a playground in their new city as a swirling wind knocked leaves loose from the trees above. The boys traversed monkey bars and slides before arriving at a swing, where they took turns pushing each other as high as it could go.

“This is fun!” one shouted in Spanish. “Keep pushing!”

Alexander watched on and smiled.

He came to Massachusetts because he wanted a better life for the boys and his daughter. It had been a difficult road here, and this was a rare moment of peace.

One of Alexander’s three children played at a park in Holyoke. Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff

One of Alexander’s three children played at a park in Holyoke. Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff

Their new shelter is a few blocks away from the playground, and they have their own beds and even a kitchen, much better than the Cambridge courthouse where they shared a room with dozens of families and slept each night on cots with sharp edges. Still, the building is old and the heat is iffy.

Alexander knows this is not permanent. They have nine months here under the state’s new shelter rules. If he can’t find a place by the time their stay here is up, he may move on, perhaps to Texas. Rent is much cheaper there, he’s heard, and it would be easy to find work.

His only worry is uprooting his family again. His children — who endured the terrible journey from Ecuador with him and have already had to switch schools several times over the last year — deserve better, he said.

As the sun begins to set, Alexander spotted his 12-year-old daughter sitting quietly on top of the playground, looking out at the skyline of the city that is her newest home.

“At this age she needs a lot of caring for,” Alexander said. “She needs stability. I know I’m not stable, being in a shelter. But at least they have a place to live.”

Andrew Brinker can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him @andrewnbrinker. Camilo Fonseca can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on X @fonseca_esq and on Instagram @camilo_fonseca.reports.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=67276d64660d477ba227b0bfc7dd37a9&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.bostonglobe.com%2F2024%2F11%2F03%2Fbusiness%2Fboston-massachusetts-section-8-shelter-migrants-housing-homeless%2F&c=16784582139860917064&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-11-02 13:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.