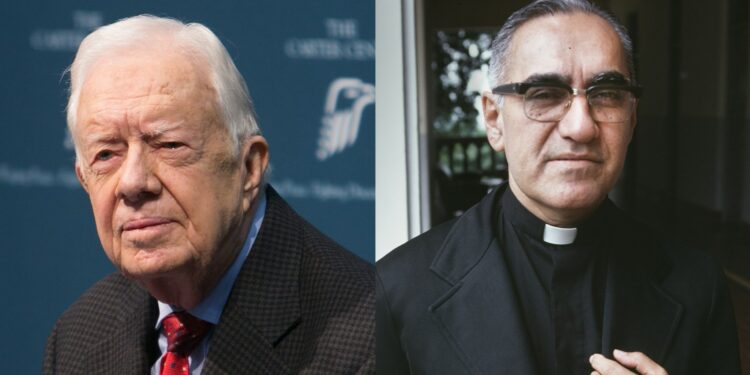

President Jimmy Carter, who died Sunday, is remembered as a humanitarian and a champion of human rights around the globe. His legacy, though, includes supporting a military regime in El Salvador during the beginning of the Salvadoran Civil War, including the assassination of Saint ├ōscar Romero.┬Ā

The United States sent military and economic aid to the government of El Salvador during its bloody 12-year civil war, and trained military leaders. A reminder that the Cold War was not always ŌĆ£cold,ŌĆØ 75,000 people were killed in the war, most at the hands of the military and death squads. Some consider it less of a civil war and more of a proxy war; AmericaŌĆÖs justification for its involvement was that communism was spreading from the Soviet Union, Nicaragua, and Cuba. But in reality, the leftist guerrillas were motivated more by the material conditions within their own country ŌĆö extreme economic inequality ŌĆö than by any kind of international movement. Some experts speculate that the guerrillas would have won were it not for U.S. involvement.┬Ā

The country never fully recovered from the war, as evidenced by the hundreds of thousands of people who have fled El Salvador for the U.S. in recent years. The country has been plagued with gang violence and previously had the highest murder rate in the world; now it has the worldŌĆÖs highest incarceration rate, as its current government has jailed tens of thousands, including many thousands of innocents, under a ŌĆ£state of exceptionŌĆØ suspending basic civil liberties.┬Ā

At the beginning of the civil war, Archbishop ├ōscar Romero took an active role in arguing for human rights and an end to the violence in the country in his weekly homilies that were broadcast on the radio. While he viewed himself as apolitical, RomeroŌĆÖs pro-human rights stance naturally placed him in opposition to the Salvadoran military. Originally something of a centrist, he became radicalized when his friend, Father Rutilio Grande Garcia, a Jesuit priest, was killed. The junta, Romero said repeatedly, was killing innocent people. He endorsed agrarian reform, a program to redistribute large areas of land to the campesinos, or peasants.┬Ā

EditorŌĆÖs picks

The Carter administration was paying attention. In January 1980, the U.S. reached out to Pope John Paul II about Romero. In the letter, Zbigniew Brzezinski, CarterŌĆÖs national security advisor, noted a ŌĆ£shiftŌĆØ in RomeroŌĆÖs rhetoric. The Archbishop, he wrote, ŌĆ£has strongly criticized the Junta and leaned toward support for the extreme left.ŌĆØ The ŌĆ£extreme left,ŌĆØ he wrote, was responsible for the violence in the country ŌĆö not the junta, or the death squads.┬Ā

Brzezinski wrote: ŌĆ£We have cautioned the Archbishop and his advisors strongly against support for an extreme left which clearly does not share the humanitarian and progressive goals of the church.ŌĆØ He asked that the Pope intervene. Romero met with the Pope in Rome shortly thereafter.

But Romero kept pushing. In February, he reached out to the U.S. with great concern. He wrote to President Carter expressing his misgivings about the possibility of the U.S. sending aid to his country. The U.S. was thinking about giving military aid ŌĆö a $49 million aid package with up to $7 million in military equipment ŌĆö to El Salvador. Romero wrote: ŌĆ£the contribution of your government, instead of promoting greater justice and peace in EI Salvador, will without doubt sharpen the injustice and repression against the organizations of the people who repeatedly have been struggling to gain respect for their most fundamental human rights.ŌĆØ┬Ā

He continued: ŌĆ£For this reason, given that as a Salvadoran and as archbishop of the Archdiocese of San Salvador I have an obligation to see that faith and justice reign in my country, I ask you, if you truly want to defend human rights, to prohibit the giving of this military aid to the Salvadoran government. Guarantee that your government will not intervene directly or indirectly with military, economic, diplomatic, or other pressures to determine the destiny of the Salvadoran people.ŌĆØ

Related Content

The U.S. decided to send the aid, and Carter did not respond personally. Instead, Secretary of State Cyrus Vance responded to Romero, writing: ŌĆ£We appreciate your warnings about the dangers of providing military assistance given the traditional role of the security forces in El Salvador.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£We are as concerned as you that any assistance we provide not be used in a repressive manner,ŌĆØ Vance continued, adding that any assistance would thus go toward enhancing the armed forcesŌĆÖ ŌĆ£professionalismŌĆØ so they would be able to maintain order while using ŌĆ£a minimum level of lethal force.ŌĆØ

Romero knew he was putting himself at risk. Two days after he sent the letter to Carter, the Catholic radio station that broadcast his weekly sermons was bombed. But he had to keep going. ŌĆ£I would be lying if I said I donŌĆÖt have an instinct for my own preservation,ŌĆØ he said, ŌĆ£but persecution is a sign we are on the right road.ŌĆØ He added: ŌĆ£We are now in the middle of a current that cannot be stopped, even if one dies.ŌĆØ┬Ā

In March 1980, the day before his assassination, Romero addressed the Salvadoran National Guard, police, and the military in his sermon: ŌĆ£I would like to make an appeal, especially to the men of the army, and concretely to the National Guard, the police, and the troops. Brothers, you are part of our own people. You are killing your own brother and sister campesinos,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£The Church defends the rights of God, the law of God, and the dignity of the human person, and there cannot remain silent before such abominationsŌĆ” In the name of God, then, and in the name of this suffering people, whose laments rise more each day more tumultuously to heaven, I beg you, I beseech you, I order you in the name of God: stop the repression!ŌĆØ

The next day, while he was giving communion at the chapel of the cancer hospital where he lived, a gunman pulled up in a Volkswagen. The man entered the room, shot Romero, and fled.┬Ā

According to a nun, on the way to the hospital, Romero said: ŌĆ£May God have mercy on the assassins.ŌĆØ He was 62.

Carter called RomeroŌĆÖs assassination ŌĆ£a shocking and unconscionable act.ŌĆØ He said the archbishop ŌĆ£spoke for change and for social justice, which his nation so desperately needs,ŌĆØ and demanded that the Salvadoran government ŌĆ£bring the archbishopŌĆÖs assassins to justice.ŌĆØ

We still donŌĆÖt have all the answers about RomeroŌĆÖs killing, but the Carter administration got an inkling in November 1980, when a Salvadoran National Guard officer told a U.S. embassy political officer that Major Roberto DŌĆÖAubuisson organized a meeting a day or two before the assassination where participants drew lots to see who would carry out the killing. DŌĆÖAubuisson had been trained by the U.S. at the Defense DepartmentŌĆÖs notorious School of the Americas. In other words, the Carter administration had reason to believe that a U.S.-trained military officer orchestrated the killing of a future saint, and ŌĆö with this knowledge ŌĆö continued working with that military.

ThatŌĆÖs not to say the Carter administration didnŌĆÖt care about human rights. When DŌĆÖAubuisson visited the U.S. in mid-1980, the Carter administration was embarrassed by ŌĆ£his open presence in the country,ŌĆØ writes human rights attorney Matt Eisenbrandt in Assassination of a Saint: The Plot to Murder ├ōscar Romero and the Quest to Bring His Killers to Justice. One example of the Carter administrationŌĆÖs commitment to human rights is that it cut direct aid to Guatemala in 1977 during the Guatemalan genocide.

Debbie Sharnak, assistant professor of history and international studies at Rowan University, describes the line that Carter walked in his foreign policy: ŌĆ£By according the broad notion of ŌĆśhuman rightsŌĆÖ such a prominent place in his administration, Carter raised expectations without clearly defining the limitations of human rights and the reach of its policy. This vagueness, combined with his inability to articulate the limited capacity of U.S. influence, hampered his policy and the publicŌĆÖs perception of his effectiveness.ŌĆØ

I have been researching the Salvadoran Civil War for years. In February, I asked staff at the Carter Center whether the former president wished to answer some of my questions about RomeroŌĆÖs assassination. A spokesperson wrote back: ŌĆ£As you know, President Carter entered hospice care on Feb. 18 last year, and since then he is not providing interviews or commenting publicly on events and issues.ŌĆØ┬Ā

The president following Carter, passionately anti-Communist Ronald Reagan, made El SalvadorŌĆÖs civil war his own. When he took office in 1981, aid increased exponentially. By the end of 1981, the Salvadoran military was employing a ŌĆ£scorched earthŌĆØ strategy inspired by tactics from the Vietnam War.┬Ā

In December, between 700 and 1,000 people ŌĆö including children, elderly people, and disabled people ŌĆö were killed at El Mozote by the elite U.S.-trained Atlacatl Battalion. The battalionŌĆÖs leader, Domingo Monterrosa, attended the School of the Americas, like DŌĆÖAubuisson. When U.S. newspapers broke news of the massacre, the Reagan administration went to great lengths to convince the public and Congress that the story of the massacre was guerrilla propaganda.┬Ā

But major human rights violations happened under CarterŌĆÖs watch, as well. In May 1980, Salvadoran soldiers, alongside Honduran troops, killed at least 300 civilians trying to escape across the river in what is known as the Sumpul River massacre.┬Ā

Human Rights Watch alleges that earlier that year, officials at the U.S. embassy even worked with a death squad in the disappearance of two law students. Salvadoran National Guard troops arrested Francisco Ventura and Jos├® Humberto Mej├Ła after a political demonstration. With permission, they brought the men to the property of the U.S. Embassy. From there, men dressed as civilians put Ventura and Mej├Ła in the trunk of a private car. They were never seen again.┬Ā

There was more violence against members of the church. Maryknoll Sisters Maura Clarke and Ita Ford, Ursuline Sister Dorothy Kazel, and lay missionary Jean Donovan had been working with the poor of El Salvador when they were raped and shot at close range in December 1980. Especially after RomeroŌĆÖs killing, this event drew outrage. Carter stopped aid briefly, but he soon brought it back

Ambassador to El Salvador Robert White, committed to improving conditions in the country, said there was no evidence the Salvadoran government was investigating the murders of the churchwomen. White was, not surprisingly, removed when Reagan took office, and the new administration went to lengths to cover up the crime.

Ultimately, while Carter demonstrated an interest in protecting human rights ŌĆö and would champion the cause in his post-presidency ŌĆö he funded a country committing mass atrocities. In fact, sending lethal aid to El Salvador was one of the Carter administrationŌĆÖs final decisions.┬Ā

The New York Times reported at the time: ŌĆ£Among its last acts, the Carter State Department disclosed last week that it had sent El Salvador ŌĆślethalŌĆÖ military aid for the first time since 1977. Transfused with a quick fix of $5 million in rifles, ammunition, grenades, and helicopters, the junta seemed to have little trouble containing the guerrilla offensive, although hit-and-run strikes continued.ŌĆØ

Pope Francis declared Romero a saint in 2018.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=6777f202d600451b914de50f6b92ebd6&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.rollingstone.com%2Fpolitics%2Fpolitics-features%2Fjimmy-carter-oscar-romero-legacy-el-salvador-1235224083%2F&c=16800295702349559188&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2025-01-03 01:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.