CNN

—

Valerie Laveus filled out forms, submitted financial records and spent six months waiting for permission to bring family members from Haiti to live with her in Florida.

“They had to be vetted. I had to be vetted. There were a lot of steps,” she recalls.

For Janvier Ndagijimana and his family, the process of coming to the United States was even longer. They lived for decades in refugee camps, going through background checks and medical screenings before officials finally gave them green light to travel to the US this year.

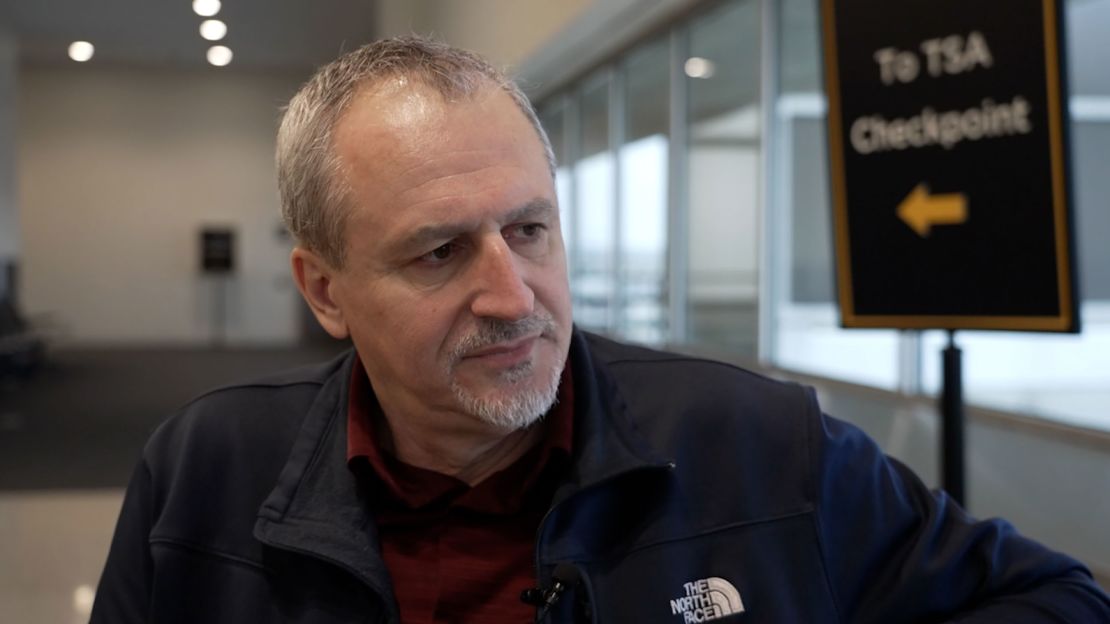

“I thought I was coming to start a new life, to be happy,” Ndagijimana told CNN through a translator. The 52-year-old Congolese refugee arrived in Kentucky just six days before President Donald Trump’s second inauguration.

But now, even though they had government permission to come to the US, these families are facing fear and uncertainty they never expected. And they’re not alone.

As he signed a slew of executive orders on his first day back in office, Trump told reporters he supports legal immigration to the US.

“I’m fine with legal immigration. I like it,” the president said from the Oval Office. “We need people and I’m absolutely fine with it.”

But new Trump administration policies are creating fear and uncertainty for many immigrants who’ve been living legally in the US, too. Among them: Refugees who recently arrived, people who received government permission to enter under a humanitarian program and migrants granted temporary protection from deportation.

“They tell you to follow the rules. They tell you they want to create a legal path for people to come, and they tell you they don’t want illegal immigrants,” Laveus says. “But then the ones who came legally, we’re turning them into illegal immigrants. That just baffles my mind. I pray that there’s a rhyme and a reason. And I pray that it sorts itself out.”

Laveus still remembers how thin her brother looked when he came to the US from Haiti in August 2023, and how timid her nephew was.

Since then, she says, they’ve dramatically transformed. Her brother, 39, is working as a janitor in the school where she teaches. Her nephew, 16, is a high school sophomore playing several sports and participating in JROTC. Someday, she says, he hopes to join the US military.

She sees how much they’ve changed in so many beautiful little ways, like how happy her brother is to go to Walmart and have the money to buy things for his son, and how excited her nephew is to ride his bike around their South Florida neighborhood, free from the fear of violence that haunted their family in Haiti.

But lately, she says, all of them have been on edge, ever since Trump ended the Biden administration program that had created a pathway for more than half a million people from Haiti, Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela to come to the United States. Participants in the program, like Laveus’ brother and nephew, received what’s known as humanitarian parole. Without the program’s protection, participants would lose their work authorization and could find themselves subject to deportation.

It’s clear no new applications under the program will be granted, but how the administration will handle the cases of participants who are already in the US remains uncertain.

A Department of Homeland Security memo issued last month suggests authorities may strip parole status on a case-by-case basis.

Laveus, a US citizen, says her family hasn’t gotten any guidance about what will happen next.

“All we have,” she says, “is this impending doom.”

Republican leaders have long argued the program itself was illegal. The Biden administration credited it with helping relieve pressure at the border by providing a legal pathway into the US.

For Laveus, the uncertainty about the future is all the more frustrating because her family followed rules they were given by the US government.

“I’ve done everything the right way. I sponsored him the way I was supposed to. He lives under my roof. We support them. And so it just baffles me that somebody that actually is working, and he’s planning on filing his taxes and contributing to society, has this pending sword over his head.”

Valerie Laveus, a US citizen who sponsored her brother and nephew to come to the US from Haiti through a humanitarian program the Trump administration has ended

“I’ve done everything the right way. I sponsored him the way I was supposed to. He lives under my roof. We support them. And so it just baffles me that somebody that actually is working, and he’s planning on filing his taxes and contributing to society, has this pending sword over his head, just ready to, just, you know, break everything and send them back spiraling.”

Laveus says she’s trying to stay positive and is praying for a solution. But fears of the dangers her family members and others would face if they’re sent back to Haiti are overwhelming.

“The airports are closed. Gangs have taken over the whole country. So what exactly are you going to do with these people? Send them back to die?” she says. “That’s just inhumane.”

Janvier Ndagijimana arrived at Muhammad Ali International Airport in Louisville, Kentucky, just weeks ago with his wife and four of their children.

It’s been decades since war and violence forced him to flee the Democratic Republic of Congo. All six of his children, he says, were born in refugee camps.

Two adult children were supposed to join the rest of the family in the US this month. But now their futures are uncertain after an executive order indefinitely paused the US Refugee Admissions Program and forced officials to cancel the family’s travel plans. It’s unclear when — or if — they’ll be reunited.

What’s more, another order the administration issued in January could force the refugee resettlement agency helping Ndagijimana and his family adjust to life in the US to reduce services they provide to newly arrived refugees.

Receiving word soon after he arrived in the US that his older children’s flight was cancelled, and that the US refugee resettlement program may no longer be able to support their family, was a shock.

“They cut off everything before I could even try to get a job to fend for my family,” he says. “It’s a pain I cannot explain. It’s too much.”

And Ndagijimana is far from the only refugee facing such uncertainty.

At Kentucky Refugee Ministries, officials say the impact has been devastating.

Federal funding to aid refugees who are already in the US, particularly recent arrivals, is frozen. That money normally covers costs for food, rent, English classes and employment services until refugees can stand on their own.

The organization told CNN it’s scaled back employee hours to make up the funding gap, turned to grant funding and dipped into its reserves to keep helping refugees as much as possible. But if federal funding isn’t restored, staff layoffs are likely, and services will have to be cut.

Trump’s recent executive order states that the US “lacks the ability to absorb large numbers of migrants, and in particular, refugees, into its communities in a manner that does not compromise the availability of resources for Americans, that protects their safety and security, and that ensures the appropriate assimilation of refugees.”

They cut off everything before I could even try to get a job to fend for my family. It’s a pain I cannot explain. It’s too much.

Janvier Ndagijimana, a refugee who learned that travel plans for his two older children to join him in the US were cancelled after an executive order suspending refugee admissions

The suspension of the US refugee program is scheduled to last for at least 90 days, and the order asks the Secretary of Homeland Security and the Secretary of State to draft a report assessing whether resuming the program would be “in the interests of the United States.”

Semsudin Haseljic, a former refugee who’s been working as a program leader for KRM for 21 years, says claims that refugees are a burden on communities are “totally not true.”

“Our refugees are becoming self-sufficient, you know, contributing to society as much as any other member of society,” he says.

Haseljic also describes refugees as “the most vetted population that comes to the United States,” detailing the numerous background checks and screenings they go through before resettlement is approved.

A coalition of refugee organizations and refugees whose travel to the US was cancelled under the executive order filed a lawsuit this week, asking a federal judge to declare Trump’s executive order illegal, block its implementation and restore refugee-related funding.

Meanwhile, families are left in limbo as they wait and pray for Trump’s decision to be reversed.

As he spoke with CNN recently about his family’s struggles, Ndagijimana sat beside one of his sons, Jacques Kagiraneza.

The 20-year-old told us that he’s also worried for his family. What will happen, he wonders, if the owner of the house where they’re living asks for rent money at the end of the month, and they don’t have it?

“We may be homeless,” Kagiraneza says.

The only thing they can do now, Ndagijimana says, is wait – and “pray to God to change the heart of the President, so he can do the right thing.”

Some Venezuelans are feeling ‘let down’ and ‘used’

Hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans who received work permits and protection from deportation under the Biden administration are also facing uncertainty.

Earlier this month, the Department of Homeland Security announced that Temporary Protected Status, or TPS, will be ending for Venezuelans who applied to the program under a 2023 expansion of protections.

Congress created TPS in 1990 as a form of humanitarian relief for people who would face extreme hardship if forced to return to their homelands. Critics of the program have argued protections that are supposed to be temporary are too often extended.

Venezuelans in the US first became eligible for TPS in 2021, and in 2023 those protections were extended to others who’d arrived since. At the time, authorities cited a “severe humanitarian emergency due to a political and economic crisis, as well as human rights violations and abuses and high levels of crime and violence, that impacts access to food, medicine, healthcare, water, electricity, and fuel, and has led to high levels of poverty.”

A new notice in the Federal Register this month states that Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem “has determined it is contrary to the national interest to permit the covered Venezuelan nationals to remain temporarily in the United States.” As of 11:59 p.m. on April 7, the notice says the deportation protections for some 340,000 Venezuelans will be revoked.

Noem has stated that the program was abused, and that participants were breaking US laws.

But an advocacy group representing Venezuelans in South Florida says officials are painting a largely law-abiding population with too broad a brush.

Recent arrests of suspected Tren de Aragua members represent a sliver of the Venezuelan population in the US, according to Adelys Ferro, co-founder and executive director of the Venezuelan American Caucus. Venezuelans who applied for Temporary Protected Status were following the legal steps the government provided, she says.

“A person who has TPS is someone who wants to live legally and work,” Ferro told reporters at a recent press conference, “because a person who has TPS has to go through biometrics, has to give their fingerprints at a USCIS office. Because a person who has TPS asks for a work permit, and gets a background check and a review of their criminal history. Because a person who asks for TPS has to prove where they live. Because a person with TPS wants to be part of the economy of this country.”

Many Venezuelans feel “let down,” says attorney John De La Vega. The Florida-based immigration lawyer says a growing number of clients are calling him, unsure of what to do.

“Imagine – people left Venezuela, they found this opportunity to be able to apply for TPS. They’re working legally in the US. Some of them have a family here and kids born in the US. They have ties to this community,” De La Vega says. “Then you tell them, ‘Listen, in two months, we’re going to put you in removal proceedings.’ This creates a big stress.”

Ferro says many in the community feel betrayed.

“We were used,” she told reporters.

“The people who supported him (Trump), including people from my community, thought that everything was referring to criminals from the Tren de Aragua, to the undocumented…and that it wasn’t going to affect people that had documents, that were in the country legally,” she says.

“He has just shown us that he is persecuting migrants, no matter what country we came from, no matter what our legal status is.”

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=67af777c6985499189c66ab5802c2d70&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cnn.com%2F2025%2F02%2F14%2Fus%2Fimmigration-refugees-trump-fears-cec%2Findex.html&c=11081493192333996130&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2025-02-13 22:01:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.