This is an excerpt from a story package about the United Fruit Company published in the March 1933 issue of Fortune. Some of the language in this article from Fortune’s archives reflects the cultural assumptions and biases of its era.

On a bitter December night in 1910 Madame May Evans of New Orleans’ ill-famed Basin Street was hostess at a lavish and memorable party. Champagne corks popped in the smoked-filled air, the piano played incessantly, and Madame Evans’ house guests shrieked with laughter as the playful gentlemen pinched their sterns. In New Orleans these gentlemen were not particularly well known, but anyone who had lived in Central America would have recognized three of them instantly as General Manuel Bonilla, ex-President of Honduras, General Lee Christmas, famous soldier of fortune, and his able lieutenant Colonel Guy (Machine Gun) Molony. One person in New Orleans who did recognize them was the U. S. Secret Service man who shivered outside in the biting cold and squinted enviously through the frosty windows at the fun.

If anyone had told the U. S. Secretary of State, the Honorable Philander C. Knox, or several of New York’s more distinguished bankers that they were responsible for General Bonilla’s presence in a brothel they would have been righteously indignant. The trail of circumstances was somewhat circuitous. Secretary Knox had been negotiating a treaty with Nicaragua whereby New York bankers should finance that country and the debt be repaid out of customs duties, over which an agent of the bankers should have control. A similar treaty lay on the desk of President Miguel Dávila of Honduras. The two persons most anxious to prevent that treaty from being signed were Madame Evans’ guest, General Bonilla, for patriotic reasons, and one Samuel Zemurray, whose reasons were commercial.

With engaging frankness and refreshing modesty Mr. Zemurray will tell how Secretary Knox had sent for him when he heard he was paying the Washington hotel expense of two Hondurans who were lobbying against the treaty, and how he explained his interest in the affair: “I was doing a small business buying fruit from independent planters, but I wanted to expand. I wanted to build railroads and raise my own fruit. The duty on railroad equipment was prohibitive—a cent a pound—and so I had to have concessions that would enable me to import that stuff duty free. If the banks were running Honduras and collecting their loans from customs duties, how far would I have gotten when I asked for a concession? I told him: “Mr. Secretary, I’m no favorite grandson of Mr. Morgan’s. Mr. Morgan never heard of me.’ I just wanted to protect my little business. Manolo Bonilla and I were working for the same thing. Why shouldn’t I help him?” Why not indeed?

Samuel Zemurray became president of United Fruit in 1938.

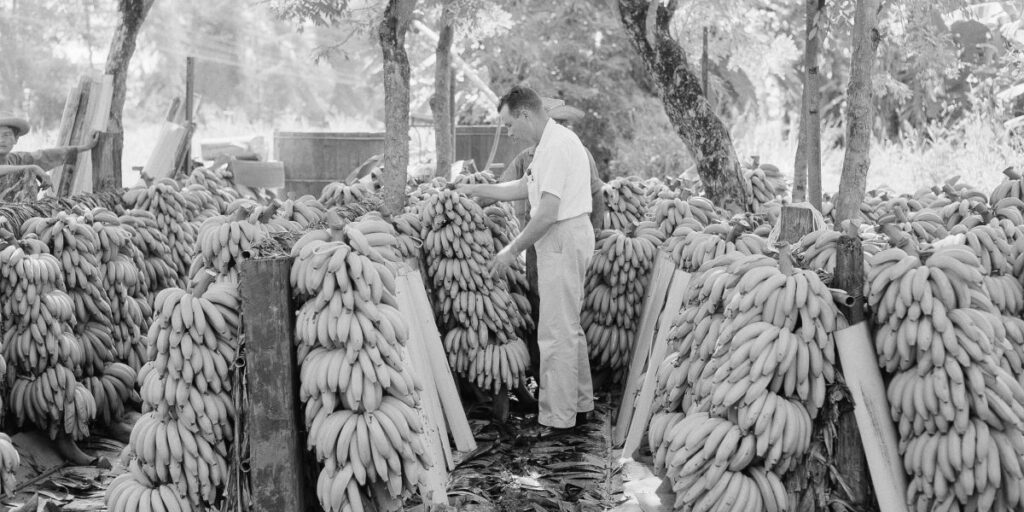

AP Photo

And so Manuel Bonilla hunted up Lee Christmas, who would fight anybody at the drop of a coin, and went to New Orleans to see Sam Zemurray. For a few thousand dollars which Mr. Zemurray was proud to lend him he acquired the yacht Hornet, built in 1890 for the late Henry M. Flagler, railroad tycoon, and used in the Spanish-American War by the U. S. Navy, which had fitted two-inch armor about the engine room. Secret Service men kept close watch on General Bonilla’s movements, with the result that the Hornet‘s captain had difficulty in getting his clearance papers. Then suddenly one night orders arrived from Washington to clear the Hornet for Nicaragua. Manuel Bonilla, Lee Christmas, and Guy Molony, who would not have been allowed on board, saw her off and then went to call on May Evans.

At two o’clock in the morning the Secret Service man outside the window retired to a telephone booth and called his chief. “It’s nothing but a drunken party in the District,” said he. Then he went home.

“Well, compadre,” said Lee Christmas to Manuel Bonilla, “this here’s the first time I’ve ever heard tell of anybody going from a whorehouse to a White House. Let’s be on our way.”

Five minutes later Madame Evans’ establishment was empty except for the ladies leaning out of the windows watching their guests run. The guests piled into two motors cars, raced for the old Spanish fort on Bayou St. John. There they went aboard Sam Zemurray’s forty-foot cruiser which he kept for fishing and other private business. The cruiser crossed Lake Pontchartrain, passed out through the Rigolets into Mississippi Sound, and made for Biloxi. There it met the Hornet. Out of the smaller boat came a large case of rifles, 3,000 rounds of ammunition, and a machine gun for Guy Molony. Mr. Zemurray waved Godspeed and the Hornet headed for Honduras.

On her heels was a U. S. gunboat. President Dávila had been notified of the Hornet‘s mission, had hastily signed the treaty, and called on Washington for protection. But the Hornet was fast. When the gunboat dropped anchor at Truxillo, where that earlier adventurer William Walker had been killed, the revolutionists had taken the town and moved on to the next seaport. Hungry Guy Molony took La Ceiba with six men and Lee Christmas arrived to find him eating a goat steak. Tegucigalpa, the capital, fell without a battle and only four members of Congress voted to ratify the treaty Miguel Dávila had signed. Manuel Bonilla was highly indignant at the U. S. for sending a gunboat into Honduran waters and wanted to demand heavy damages. Mr. Zemurray talked him out of that. President Bonilla was so grateful to Sam Zemurray that he gave him whatever concessions he asked for and didn’t charge him a penny. He even gave concessions to Mr. Zemurray’s friends. That revolution saved Honduras from the bankers and left it free to be conquered by the fruit companies.

Between Guatemala and Costa Rica the map of Central America swells like a gangrenous leg. Where the swelling is greatest is Honduras. Three-fourths of it is mountains, in the center of which hides the remote capital, Tegucigalpa. Southwest of Tegucigalpa the jagged mountains drop sharply to the Pacific, where the lonely port of Amapala squats apologetically in the middle of the Gulf of Fonseca. Northward the mountains slope gently down to the plain across which the Ulua and Chamelecon rivers corkscrew their way to the Caribbean. There stretches a section of the Caribbean coast, one hundred miles long and twenty-five miles deep, which is drained and sometimes flooded by half a dozen rivers. It is a hot, wet, fertile province known officially as Atlantida and popularly as the North Coast. It is there that the bananas grow. Like other Central Americans who cared to remain alive, Hondureños once refused to live on the dank North Coast. Bananas changed all that.

Before the bananas came the railroad. In 1868 a civil engineer named John C. Trautwine was commissioned by the government to build a railroad from malarial Puerto Cortés on the North Coast up the mountains to Tegucigalpa. Mr. Trautwine was a practical man; he was being paid by the kilometer and he did not like the look of the mountains. Back through the level jungle his railroad wound, matching curve for curve with the Chamelecon until, fifty miles inland, just past the town of San Pedro Sula, the money gave out. Full of regrets, Mr. Trautwine collected his profits, returned to the States, and wrote a handbook for civil engineers which today is highly esteemed in institutes of technology. Lee Christmas, who was a color-blind engineer long before he became a revolutionist, drove his first locomotive over the National Railway and spat out of the cab window. “—–!” said he, mentioning the first syllable of his surname. “What a hell of a way to build a railroad!”

For years before Manuel Bonilla’s revolution fruit boats used to anchor off Ulua Bar and at the mouths of the smaller rivers and take on loads of bananas floated out in lighters. The fruit was several days old when loaded, the supply was irregular, and the labor costly, and so Honduras was no great shakes of a banana country. Truxillo and La Ceiba were small ports without railways. Tela was a tiny village and here and there were tinier Carib villages of thatched manaca huts. In Puerto Cortés lived engineers and firemen who worked on the railroad, Chinese, Turkish, and Syrian storekeepers, professional ladies en route from Marseilles to Port Said, professional soldiers looking for trouble, and a variegated assortment of tropical tramps who found it very convenient to live there because Honduras had no extradition law. (But one has since been enacted—in 1918.) It was in Cortés that Richard Harding Davis became fascinated by his romantic conception of Lee Christmas, in Cortés that O. Henry lived as an outlaw, in Cortés that John A. Morris conducted the great Louisiana Lottery of the 1880’s and 1890’s. Between Cortés and San Pedro were a few shacks along the railroad. Most of the coast was jungle.

A.L. Barnett—Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG/ Getty Image

The Cuyamel Fruit Co. began the banana boom. Mr. Zemurray’s organization operated at Omoa, halfway between Cortés and the Guatemalan border. East of Cortés, at Tela and 100 miles down the coast at Truxillo, he got concessions for his friend Minor C. Keith, vice president of United Fruit. The concessions were in the names of the Tela Railway Co. and the Truxillo Railroad Co. The concessions called for construction of so many miles each year—enough to reach to Tegucigalpa—but instead of going straight inland the roads have spread laterally, to tap the banana lands. Minor Keith thought in terms of railroads, but United Fruit thought bananas. The North Coast soon began to fill up. Engineers came up from Costa Rica and Ecuador, boasting into their whisky of the fever on the Guayaquil-Quito job and cursing the gauge of Mr. Trautwine’s railway for exactly what it was.* From Louisiana and Texas came woodsmen and cattlemen and farmers and hard young men who would do anything. From Jamaica and other West Indian islands came black, strong Negroes immune to fever. Down from the foothills came the Hondureños who would risk malaria for the high wages the gringos paid. And with them, swinging their machetes, came the thieves and cutthroats of Honduras.

Beside the little village of Tela a new, bigger town sprang up. Out from the beach ran a new wooden pier. Back into the country a railroad cut through the jungle, and behind the railroad were the woodsmen and the farmers flattening out the jungle in a mad rush to get more banana land. Before the Tela Division was finished United Fruit was building Puerto Castilla on a sand spit out from Truxillo and turning 30,000 more acres of jungle into bananas. Mr. Zemurray moved in behind Cortés, across the Ulua from United Fruit’s Tela. His fellow townsmen, the Vaccaro Brothers (now the Standard Fruit & Steamship Co.) were already established at La Ceiba between United’s Tela and Truxillo holdings. Before 1920 the entire North Coast of Honduras was controlled by U. S. corporations. When, in 1930, United Fruit and Cuyamel became one, the banana lowlands of Honduras became for practical purposes the property of the corporation they formed.

Lee Christmas died in 1924, but the revolutions went on. Last November Guy Molony, older and fatter, captured a machine gun and chased a band of rebels out of San Pedro. On the beach at Tela seven revolutionists lay dead and buzzards feasted. One of his own men shot Willie Coleman in the back of the head and they laid him out in the disintegrating rain at the entrance to the graveyard where everyone could see. Nobody but his native wife was sorry Willie died. He was a bad hombre and had never approved of corporations.

*Rails are usually laid fifty-six and one-half inches apart (standard gauge) or thirty-six inches apart (narrow gauge). Mr. Trautwine built his railroad on a third, less common gauge of forty-two inches. This is appropriately known as bastard gauge.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66b09141a79a42ee889f431721a0c034&url=https%3A%2F%2Ffortune.com%2Farticle%2Funited-fruit-conquest-honduras-swords-buzzards%2F&c=6322901420589480467&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-08-04 00:08:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.