Just going to leave this hereтАж.

Fouls per card at the Copa America so far.

5 CONCACAF teams at the top ЁЯдФ

My other observation is that #USMNT needs to foul more and play more physical. CanтАЩt be so naive to this type of game in KO tournaments. pic.twitter.com/DRrkgYdrZU

тАФ Stu Holden (@stuholden) July 3, 2024

Uruguay, notably, are at the bottom of that table, averaging one yellow card per 36 fouls in the group stage, which fits the popular characterisation of La Celeste as being one of the most streetwise teams in the world. Or, to put it another way, Uruguay know how to foul and get away with it.

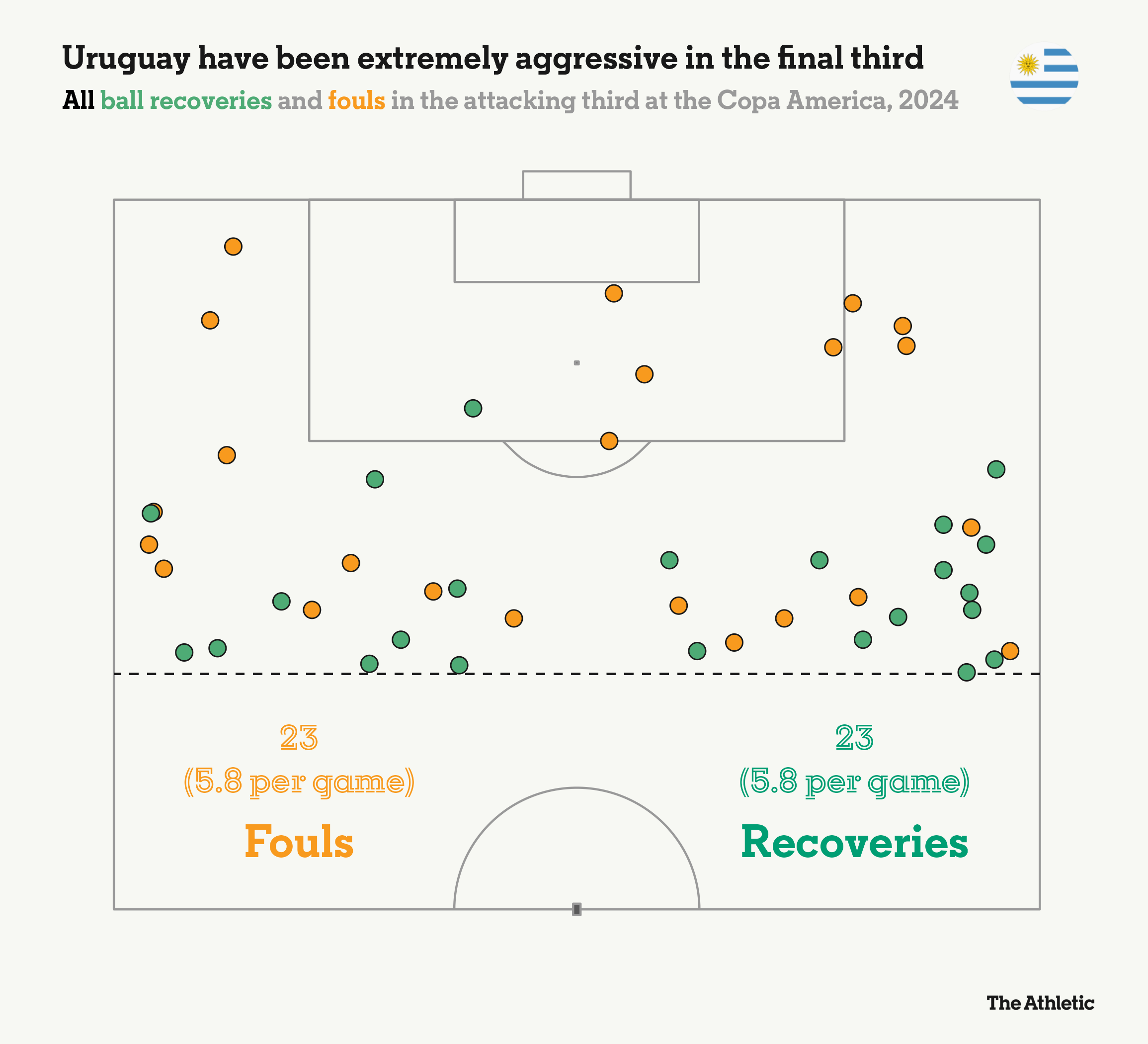

That feels true to a point, but itтАЩs not quite as simple as that for a couple of reasons. The first thing to say is that Marcelo BielsaтАЩs team press high and aggressively, which leads to a high proportion of fouls being committed in the attacking third (5.8 per game, which is more than any other team at the Copa America).

They are the kind of fouls that rarely lead to a yellow card because of the area in the pitch where they occur and, generally, the challenges arenтАЩt aggressive. Crucially, though, those fouls prevent the opposition from playing through UruguayтАЩs press and counter-attacking.

There are numerous examples of Darwin Nunez, Nicolas de la Cruz, Facundo Pellistri and Maximiliano Araujo тАФ generally UruguayтАЩs four most advanced players тАФ committing that type of foul in the Copa America. Indeed, that attacking quartet is responsible for 26 fouls between them in four matches, which is more than the entire USMNT made across their three group games.

If weтАЩre generous and give those attacking players the benefit of the doubt, they are often running at maximum speed and itтАЩs hard to apply the brakes. An alternative view would be that anyone leading UruguayтАЩs press is not going to allow the opposition to play out, or break the lines, come what may.

Are they under explicit instructions to foul in that scenario? Nobody in the Uruguay camp would ever publicly admit that, but it wouldnтАЩt be surprising and that goes for the tactics of plenty of other countries, too, mindful of what we see regularly at club level.

In AmazonтАЩs All or Nothing documentary series covering Manchester CityтАЩs 2017-18 season, Mikel Arteta, then assistant to Pep Guardiola, tells the teamтАЩs attacking players to make fouls if there is a transition. The logic is simple: the out-of-possession team can regain its shape without being exposed by a counter-attack and thereтАЩs a lower probability of a yellow card being shown compared to when a defender commits a foul closer to their own goal.

The graphic below shows where exactly UruguayтАЩs fouls in the attacking third have occurred and also highlights the success that BielsaтАЩs team have had with regaining the ball in the same area through their relentless running and pressing (5.8 recoveries per game, which, again, is more any other team in the tournament).

ItтАЩs probably also worth mentioning that the smaller pitches at this Copa America tournament play into the hands of a team that presses as aggressively as Uruguay.

Watching every Uruguay foul at the Copa America confirmed something else: the standard of refereeing in the tournament has been at best inconsistent and at worst desperately poor.

It was a minor miracle, for example, that Nandez managed to avoid a booking in the group stage before his red card against Brazil in the quarter-final. The Uruguay right-back made two fouls within 32 seconds against the U.S. and both could easily have been deemed yellow card offences (the second is shown below; Antonee Robinson is under there somewhere).

De la Cruz could also count himself highly fortunate not to have a yellow card next to his name before SaturdayтАЩs wild quarter-final and only Kevin Ortega, the Peruvian referee whose performance in the final group game against the U.S. was heavily criticised, knows why he booked Tyler Adams for a challenge on Mathias Olivera when the Uruguay left-back was the offender.

With all of that in mind, it would be a stretch to say Uruguay have cracked the code when it comes to knowing how to stay just the right side of the line with yellow cards. In reality, they got off lightly before facing Brazil and they were not alone in that respect.

What is clear is that how Uruguay get on top of teams in the final third, legally or illegally, is a fundamental part of their game under Bielsa. Cynical at times? Yes. Effective? Damn right. Their opponents are simply unable to get into any flow.

Some neutrals will rage, especially when UruguayтАЩs fouling can seem so systematic, which was the case against Brazil. But there are also plenty of people in South America and beyond who marvel at how a country of only 3.4million people can keep finding ways to triumph against the odds.

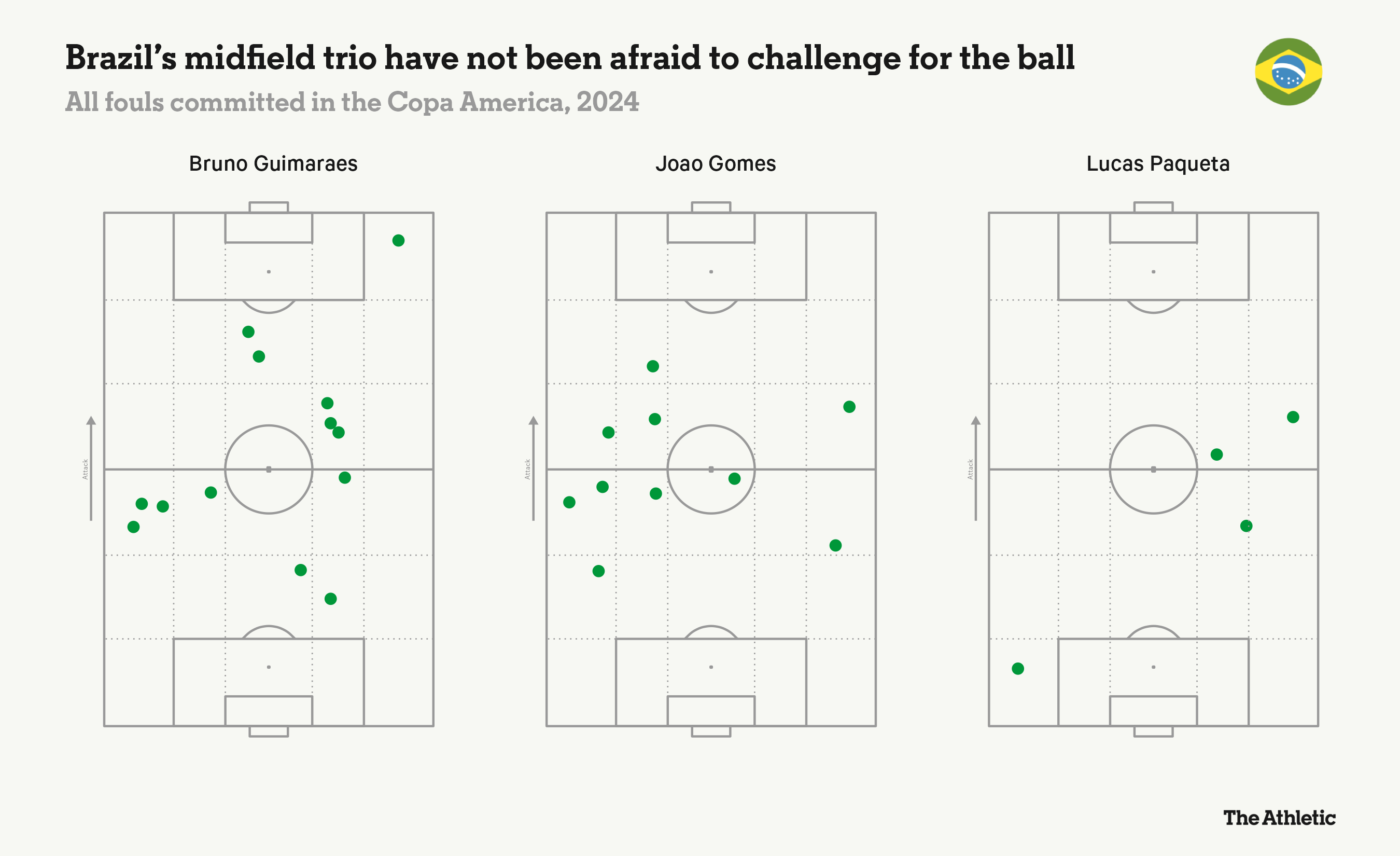

Brazil were not all sweetness and light either. In their case, the midfield was the area where the majority of their fouls were made тАФ often petty, arguably deliberate at times and generally disruptive to the opposition.

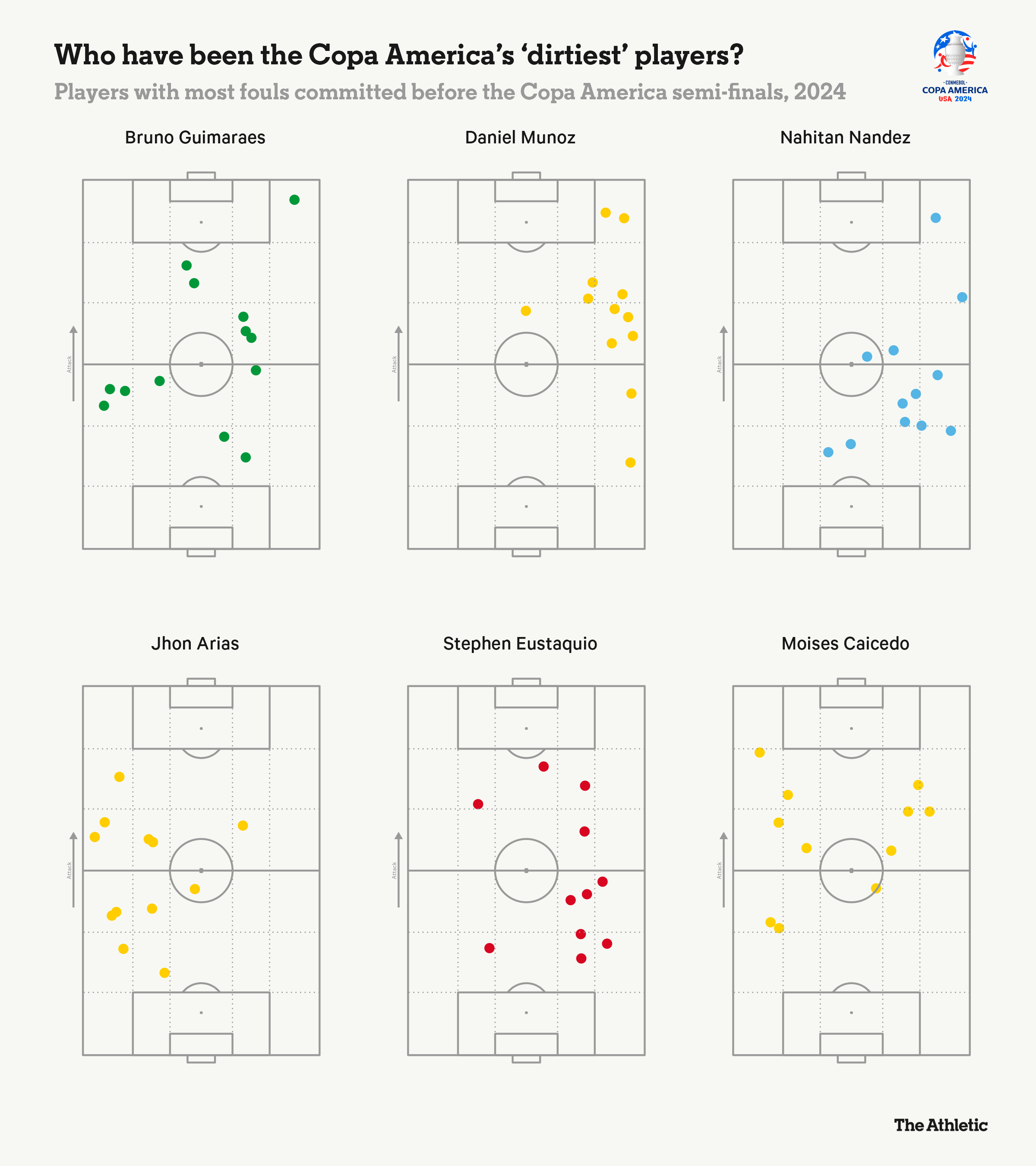

The chief protagonists were Bruno Guimaraes, who has committed more fouls (13) than anyone else at Copa America, and Joao Gomes (10). As for Lucas Paqueta, he made more tackles than any other Brazil player, committed only four fouls but ended up with two yellow cards, which was twice as many as Guimaraes.

Gomes made half of his 10 fouls against Uruguay and it is no exaggeration to say the Wolves midfielder could easily have been booked on three separate occasions (each of those challenges is shown in the first three pictures below) before finally receiving a yellow card for a lunge on Nandez (the fourth image).

Dario Herrera, the Argentinian referee, was lenient throughout, letting things slide early in the game. In that sense, he was like the supply teacher who walked into the lesson and was viewed as a soft touch within minutes. What followed was anarchy.

The free-kick patterns are not so obvious with Argentina, but there are still some interesting themes, the first of them being that Lautaro Martinez, the leading goalscorer at the Copa despite only starting two matches, averages a foul every 26 minutes, which is pretty much the same as Guimaraes.

MartinezтАЩs fouls are often from behind, when heтАЩs chasing back with little chance of getting the ball, and force the opposition to restart and rebuild their attack.

Something else jumps out when you watch Argentina out of possession and that is the way their two centre-backs, Cristian Romero and Lisandro Martinez, squeeze high up the pitch when the team is attacking and refuse to allow anyone to go past them if the ball is turned over.

Both Romero and Martinez close down their opponent quickly and aggressively, get overly tight and think nothing of making a tactical foul in the opposition half. In fact, you get the impression thatтАЩs all theyтАЩre thinking about at times.

They are also experts at turning on their heels and fleeing the scene as quickly as possible, barely giving the referee time to blow his whistle, let alone show a yellow card.

Most significantly, that type of foul stops Argentina from being vulnerable to a counter-attack and enables the team to regain its defensive structure, with every player behind the ball.

Below is an example of each one of those steps unfolding in the Ecuador quarter-final, when Romero clattered into the back of Enner Valencia and even had his arm around the strikerтАЩs head but somehow avoided being cautioned.

And here is Lisandro Martinez doing something similar against Chile after тАФ and this was a collectorтАЩs item тАФ Lionel Messi lost control of the ball near the edge of the penalty area.

How Martinez reacts to the transition is fascinating: he closes down Eduardo Vargas at breakneck speed, cynically cleans the Chile striker out after he gets turned, sprints away without even waiting to see how the referee will respond to that challenge. Argentina are now back in their 4-4-2 out-of-possession structure.

Our final case study is Colombia, who have played beautifully at the Copa America, scoring 11 goals across four matches and producing fast, free-flowing football. But they also have a couple of persistent foulers in Jhon Arias, hugely impressive in the half-space on the left, and the rampaging Daniel Munoz on the right.

Munoz locks down that right flank, where he attacks and defends aggressively. The Crystal Palace defender has two goals, one assist, and has committed 12 fouls тАФ the joint second-most at the Copa America тАФ but avoided a yellow card. Seven of those fouls were against Brazil and three of them on Vinicius Junior тАФ a point that the winger made to the referee (see the clip below).

Persistent fouling tends to go unpunished here because, it seems, the threshold for showing a yellow card is so high and naturally that plays into the hands of some players.

Indeed, the graphic below, which includes a CONCACAF player in the form of CanadaтАЩs Stephen Eustaquio, makes for interesting reading.

Where on earth is Jefferson Lerma, you might ask?

Lerma, remarkably, has committed only one foul in the Copa America so far.

Alas, some things never change: the Colombia midfielder still managed to pick up two yellow cards and get suspended for the quarter-finals. Quite a feat, that.

(Top photo: UruguayтАЩs Nahitan Nandez brings down BrazilтАЩs Rodrygo; Ian Maule/Getty Images)

Source link : https://www.nytimes.com/athletic/5624771/2024/07/09/copa-america-tactical-fouls/

Author :

Publish date : 2024-07-09 06:17:24

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.