Later that year, the Hunterian was set to open a new exhibit as a part of a larger project called Curating Discomfort, intended to reassess collections, displays, and labels that perpetuate ideologies of colonialism and white supremacy within the museum. The objects in the exhibit would not be chosen by the Hunterian’s staff, but rather by a team of curators of color comprising retired schoolteachers, research students, and lecturers from other universities. When Rutherford was asked to pass along a shortlist of zoological specimens for the exhibition, he immediately thought of the galliwasp.

When England invaded and colonized Jamaica, it steamrolled the island’s forests into sugarcane plantations, disappearing the galliwasp’s native habitat. The plantations quickly became metropolises for rats, which arrived as stowaways on British ships, so the British introduced Indian mongooses to eat the rats, which they did, along with the many small creatures of Jamaica. All this contributed to the extinction of the giant galliwasp and other native species, such as the Jamaican rice rat. “It was this ecological disaster that went on in Jamaica,” Rutherford said. Given this context, one curator named Churnjeet Mahn selected the galliwasp for the exhibit and wrote a description of the species’ extinction: “Here we can see how colonialism contributed to the devastation of ecosystems that cannot be repaired, and for which there is no restitution.”

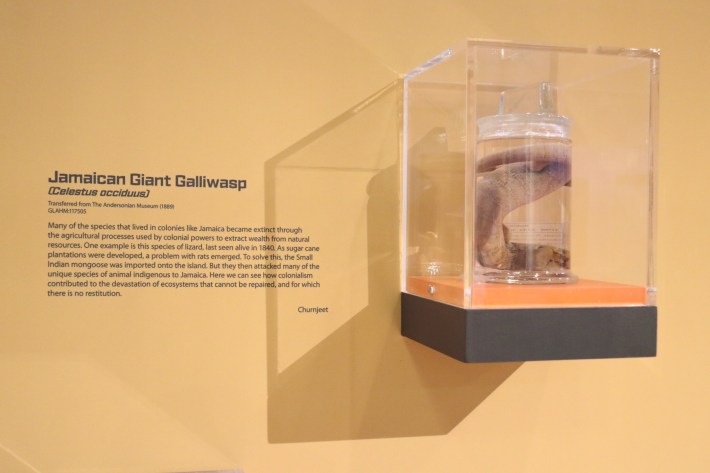

The Jamaican giant galliwasp specimen on display as a part of Curating Discomfort. | The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

The Jamaican giant galliwasp specimen on display as a part of Curating Discomfort. | The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

Rutherford realized Curating Discomfort marked the first time that the Hunterian’s Jamaican giant galliwasp had gone on display in decades. He dug around online databases to track down other specimens. He saw they were held around Europe and North America, but nowhere in Jamaica itself. “Once this comes off display as part of Curating Discomfort, what’s going to happen next?” he said. Rutherford asked his bosses if he could approach curators in Jamaica to potentially repatriate the object. When he got the go-ahead, he emailed Roper. For her, the choice was clear. “Absolutely,” she emailed back.

Galliwasps, in general, are not popular in Jamaica. The lizards resemble snakes with legs, an appearance that has earned the island’s surviving galliwasps a bad rap despite the fact that people rarely encounter the shy reptiles. “Growing up, you would hear the folklore about galliwasps, which is that if it bites you, you have to get to water before it does, or you’ll die,” said Calder, who has appreciated reptiles since childhood. This is false; galliwasps are not venomous and will only bite defensively. When Calder was a preteen, a galliwasp bit his finger. He remembers running around, galliwasp dangling from his finger, in search of a camera to prove the folklore wrong. “I proudly was telling people yes, it bit me. I didn’t wash my hands. It didn’t draw blood, and I’m alive,” he said.

But the giant Jamaican galliwasp is familiar to and much more beloved by those working at Jamaica’s collections. Elizabeth Morrison, a zoologist at the Natural History Museum of Jamaica at the IOJ, first learned of it when she joined the museum more than 30 years ago. But she only encountered the reptile in writings and illustrations, such as Sloane’s clumsy rendering. “I had always wanted to see one,” Morrison said. Newell, the entomologist, also learned about the giant galliwasp when she joined the museum more than 20 years ago. She’d learned a specimen was at the Natural History Museum in London, and when she traveled there for a conference, she asked if she could see it. “I was more interested in seeing it so I could come back and tell everyone that I saw it,” Newell said.

Roper’s emails with Rutherford started a repatriation process that would last 19 months. “Originally, I hadn’t had much of a plan beyond sending it back,” Rutherford said. “And that could have been just the lizard in a DHL package.” But the curators’ early conversations made it clear that the process should be bigger than DHL. In 2019, the University of the West Indies and the University of Glasgow signed a reparative justice agreement acknowledging that the Scottish university, which helped lead the abolitionist movement, also benefited from slavery. The galliwasp’s repatriation would proceed under this agreement. “The layman understanding of repatriation is you get back your stuff,” Roper said. But this stuff is often barricaded behind policy, legislation, and institutional practice, she added, and the curators wanted to return the object in a way that would benefit both institutions. “We’re literally setting the tone for natural history repatriation in the Caribbean.”

A plan emerged to send a delegation of Jamaican researchers including Morrison, Newell, and Roper to Scotland. They secured funding and traveled in the spring of 2024, which coincided with a repatriation conference in Scotland. And at the Hunterian, the Jamaican researchers got to see the galliwasp in person for the first time. “In my mind, I had built it up so much,” Morrison said of the lizard, which, to be fair, is literally called giant. “It was in a smaller container than I thought.” But Celeste was preserved better than others, Roper said, adding that the specimen at the Natural History Museum in London is the least attractive one she’s ever seen.

The repatriation team from the University of the West Indies, Institute of Jamaica, and The Hunterian. From left: Morrison; UWI graduate student Desireina Delancy; Tannice Hall, a lecturer in life sciences at UWI, Shani Roper, Dionne Newell, and Mike G. Rutherford. | The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

The repatriation team from the University of the West Indies, Institute of Jamaica, and The Hunterian. From left: Morrison; UWI graduate student Desireina Delancy; Tannice Hall, a lecturer in life sciences at UWI, Shani Roper, Dionne Newell, and Mike G. Rutherford. | The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

Morrison assisted in taking DNA samples and helping Rutherford prepare the lizard for its journey. They removed it from its ethanol tomb, wrapped it in cheesecloth to keep it moist, and then vacuum-sealed the whole thing—not the most dignified packaging, but the most secure for commercial air travel. Celeste had an unexpected layover when a travel security agent briefly seized the package, which had an image of a preserved giant galliwasp—the unattractive one in London—on the cover. “She didn’t know a lizard could come through the checkpoint,” Roper said.

When Celeste finally made it to Jamaica, Calder watched as the lizard was unwrapped from the cheesecloth and dipped back into preservative. He knew the specimen’s curved glass bottle slightly warped the galliwasp’s appearance. “So being able to look at it outside of that setting and look at the features in real time was really exciting,” he said. Soon, Celeste will be unveiled to the public, on permanent loan in the Natural History Museum of Jamaica. Then “we can go and look at it whenever we want,” Calder said.

The journey home was long but relatively smooth, in part because it was exchanged between two institutions, rather than two nations, which would have required a great deal of additional bureaucracy. But the Jamaican giant galliwasp was also a perfect candidate for repatriation. It was endemic, meaning only found in Jamaica. It is presumed extinct, meaning no new ones could ever be collected. It is an icon of Jamaica’s biodiversity, and there were no specimens in Jamaica. But Roper hopes this return can lead to more repatriations to Caribbean nations. “It’s kind of opened the door for us,” she said.

Some other of Jamaica’s native species not currently represented in the museum’s collection may be held in the collections of other international museums, Morrison said. Fossil specimens of the Jamaican rice rat, which went extinct in the 19th century, are held at the University of Florida. And the holotype of the Jamaican monkey Xenothrix mcgregori, thought to have gone extinct in the 1700s, is held at the American Museum of Natural History. “I am sure there are others out there,” Morrison said.

Elizabeth Morrison receiving the galliwasp from Mike G. Rutherford. | The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

Elizabeth Morrison receiving the galliwasp from Mike G. Rutherford. | The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

“It’s very important for you to have agency over your history, be it anthropological or natural,” Calder said. In the case of the galliwasp, Rutherford was the first to reach out about the return. Roper believes museums in the Caribbean should be strategic in their requests, focusing on what will enhance their collections. Similarly, Newell said it is important for museums in former colonial territories to know about objects and specimens of particular cultural, religious, or biological significance. And if the museums have the capacity to house these items, “repatriation should be considered,” she said.

Beyond collections, museums in formerly colonized nations lack the resources of their colonial counterparts, such as facilities, staff, and exhibit spaces. To Roper, the most memorable aspect of the trip to Glasgow was not seeing the fabled galliwasp but seeing the collections storage facility in which it was stored: vast shelves with motion-sensitive lighting. “To me, those are luxuries of the highest order,” Roper said. “I learned so much about being there, and just what’s possible if you have resources.” So the goal of repatriation might take a backseat to more urgent institutional needs. One major focus of the Museums Association of the Caribbean is disaster risk, as extreme weather events worsen under climate change; Roper and I had to reschedule our initial call because Hurricane Beryl was sweeping through the Caribbean. “We’re currently in hurricane season,” Roper said. “Disaster risk is essential to our survival.”

Celeste’s return has already sparked newfound public engagement with Jamaica’s museum collections, as the curators have done a tour of interviews on local television and radio stations. In Morrison’s experience, sometimes Jamaican children don’t believe they can become a scientist or a herpetologist, or work in a museum. “It’s that sort of inspiration that I’d like to see when our when our specimens are repatriated and our museums developed,” she said.

The return of the island’s unique species would benefit research, conservation, culture, and national pride, Newell said. She hopes for more returns of such specimens. “That’s what I would like to see,” she said. “Sooner rather than later.”

Recommended

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66bcb69c8e414dfdb4960d2e415285c4&url=https%3A%2F%2Fdefector.com%2Fhow-a-170-year-old-lizard-finally-came-home-to-jamaica&c=16851999759504706121&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-08-14 02:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.