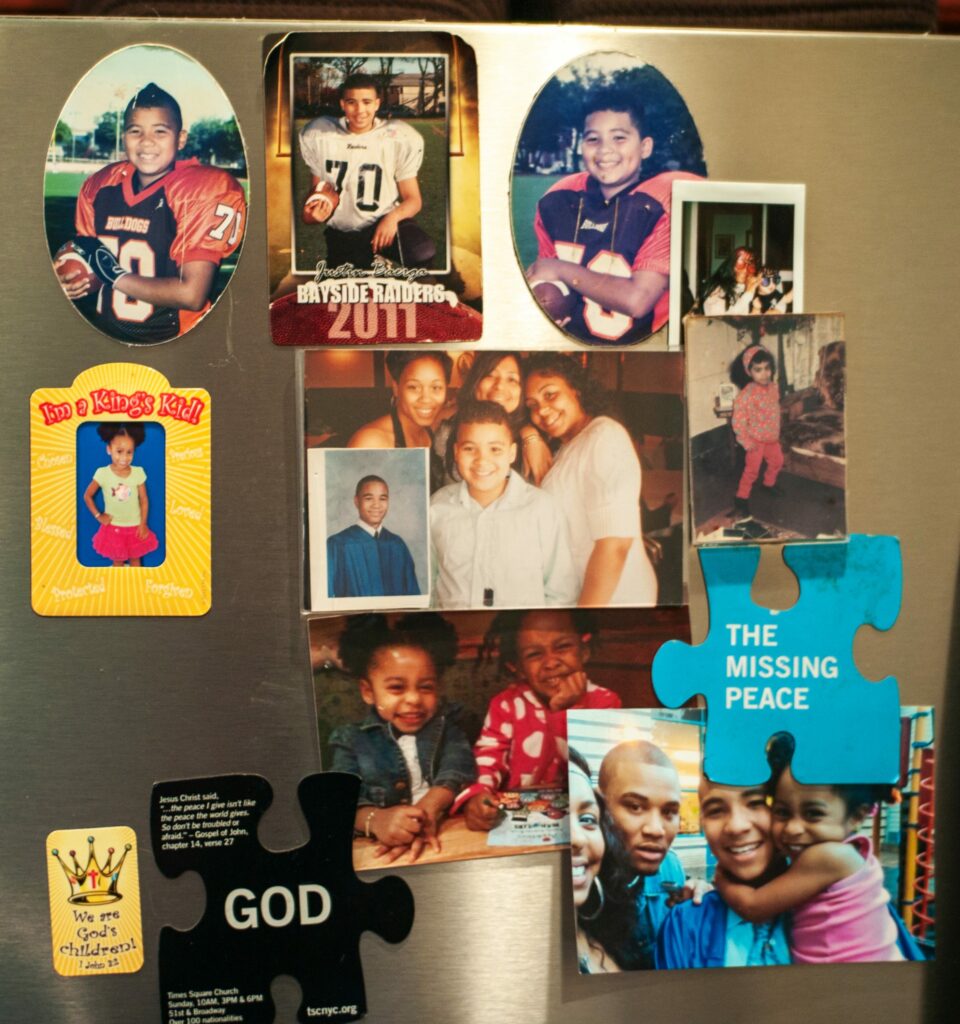

“There’s no pain like that pain,” says Peggy Herrera, tears welling up, about the death of her son. Herrera describes her 24-year-old son Justin as her “little man.” He’s reflected in photos in almost every part of her Long Island home, where she moved from Jamaica, Queens, at his plea for somewhere safer and different to live. Anyone who talks to her would immediately note her expressions of love and doting care of her son.

Justin, who stood 5 ’11”, played football competitively since childhood, and struggled with the loss of his father at a young age, was celebrating his birthday with friends on July 2 when he was shot to death.

“When my son was killed, I didn’t know what the next step was,” Herrera said. She needed financial support, but said she was unaware of victim compensation at the time of his murder and misinformed about when and how to get it.

New York’s Victim Compensation program has awarded funds to victims and survivors of violent crime since the federal law was enacted in 1984.

Life for many is thrown into chaos after surviving a gun injury or losing a loved one to gun violence. Home may no longer be a safe haven, survivors face months of recovery and doctors’ visits, and families struggle with funeral costs. The loss may have been a parent, a child, a sibling, a provider, a leader of the family. Everyone grieves for a loss or altered life differently, and the high costs of therapy and trauma recovery often keep mental health care out of reach.

In New York, applicants may qualify for up to $30,000 in lost wages or support, up to $2,500 for moving expenses, or up to $2,500 for crime scene cleanup after an incident of gun violence. For funeral costs, the reward is $6,000, which has not increased since the 1990s. Some recipients said these amounts barely cover the costs of funerals or relocating from their homes for safety. For example, the average cost of a funeral with a burial vault is $9,995, according to the National Funeral Directors Association.

Victim compensation for many, whether reimbursement, one-time, or recurring payment, only scrapes the surface of financial burdens that follow the violent injury or death of a loved one.

Telling their stories

Gwendolyn Halsey, a mother of five and retiree from the New York CIty Transit Authority, said all of her children have been shot, and one died. She remembers the day that her son James Velz Halsey was killed six years ago: It was a Saturday, and he had asked her to come to Brooklyn to ad lib on a song of his. Her son and grandson had just come back from the store when she overheard an argument start outside their home. She said she partially opened the door to see if everything was OK. He replied, “Yeah, Ma.” Shortly after she went back in the house, she heard three shots. “I was frozen. I couldn’t move,” she said.

Halsey is left with memories of her son’s body splayed on her front steps and having to clean the brain matter left behind after the police came to the scene. She said she received some victim compensation — a one-time payment for funeral expenses — but currently doesn’t have a home of her own and has been staying with a relative.

Tragedy came to Janifer Taylor’s doorstep, too. She was living in Virginia when her daughter, Dawn Peterson, asked her to move to New York to live with her in 2020. She couldn’t have anticipated that she would have just 16 months left with her only child. Peterson, then a mother of a two-year-old daughter and 18-year-old son, was gunned down on December 17, 2021, in front of their home by an unknown man. Taylor was home when she heard the shots. Footage she said she later saw from a neighbor’s security camera captured Dawn’s final moments.

“She was screaming, ‘Mommy, please help me,’” she said. “That’s the pain that I live with every day and the aftermath. It’s like she’s on vacation—she may come home one day, but then you feel it; they are not coming back. It’s a pain that never goes away.”

Peterson’s case remains unsolved, Taylor said. In the aftermath, she received an emergency housing voucher, but finding a place proved difficult.

“It’s considered an emergency housing voucher, but it took me two and a half years to find a place to live because a lot of people didn’t take this voucher,” she said.

Taylor received compensation to help cover funeral expenses in a week’s time, and she credits Carolyn Dixon and Where Do We Go From Here, a support organization for grieving families, for helping her navigate that process. “I was one of the ones that did get the $6,000 and I’m appreciative, but…it definitely wasn’t enough,” she said.

In New York, applicants can qualify for up to a $3,000 emergency award within 24 hours of filing, but when it comes to processing compensation claims, it takes 107 days on average for the agency to either award or deny an entire claim application.

The 13-year-old murder case of Monica Cassaberry’s son Jamal Singleton Sr. remains unsolved. “I think that a lot of people don’t understand,” she said. “No mother should have to bury a child. That’s not scientifically correct. It’s wrong. They should be burying us, not vice versa.”

Her son’s case made her unwilling to return to work at the police department. “After I went out on extended leave, I never went back to the police department,” she said. “I helped solve all these crimes…I felt like, why should I go back to a system that didn’t do nothing for me or mine?”

Cassaberry said her son’s shooting happened diagonally across the street from her. Soon after, she moved into her brother’s home before a shooting of her sister at her brother’s home forced her to move her family into a homeless shelter. She said it was difficult to uproot and move from her fully furnished three-bedroom home as a single mom in the aftermath of her son’s murder.

“My kids have been traumatized more than once…and then, not only are you getting traumatized by the shooting, you turn around, move somewhere else that don’t work out, then you end up in the shelter system,” she said.

“Any family who has been inflicted or impacted by gun violence should never be in the shelter. That;s the worst place,” Cassaberry added. “They need to have something set up for families and victims of crime. They need to have special housing for us.”

Cassaberry said housing is an under-realized need for victims of crime.

“A lot of families are still stuck in places where they have bullet holes in a window or a wall,” she said. “I would if I had the heart—I would have still been living where my son was shot diagonally from where I lived. I couldn’t do it.”

A myriad of compensation programs

New York has more than 200 victim assistance programs—nonprofits and advocacy organizations where New Yorkers can get help with applying for victim compensation. Pathways, a Kings Against Gun Violence’s (KAVI) program, is one of them, opening its doors on the third floor of Restoration Plaza in Bed-Stuy back in July. Program Coordinator James Peele said their program takes walk-in clients, along with referrals made at Kings County Hospital, where KAVI makes connections with future clients.

“I’m hoping that we are able to allow the community to know what resources and funds are available to them as crime survivors and victims of crime,” Peele said. “Different things that they may need—helping them with finances, funeral costs, hospital bills—some resources that they might not even have known were available to them and that they’re owed as victims of crime.”

Gun violence is one of many reasons people seek victim compensation. Applicants also seek relief from domestic violence, sexual abuse, homicide, and assault, which are among the most common reasons.

Peele said therapy is among the most pressing needs that come up for gun violence survivors. Centers like Pathways offer a safe place for victims and survivors to come and start the process. Peele said the program can reach people who would otherwise be intimidated by pursuing compensation.

“People [who] come into these situations are kind of scared of dealing with governmental affairs, for many reasons,” he said. “But I think one thing they should know: that these phones and resources are not only a gift but more so, required by law to help them through that situation.”

According to NY State Senator Jabari Brisport, who was also in attendance, “Violence is one of the most disruptive things in our communities when it happens. And it’s always a ripple effect, right? It’s never just simply the one victim, but also their friends and families who are impacted.”

KAVI’s work plays a crucial role: “They deserve all the resources and all the funding that myself or the state can give because it truly is a life-saving operation that they’re doing here,” he said.

Improving victim compensation

This year marks 40 years since the passage of the Victims of Crimes Act (VOCA), the law that established victim compensation funds. In University of Michigan sociologist Jeremy Levine’s words, the law was “the tail end” of a two-decade fight to get a federal subsidy for victim compensation. When the concept of financially supporting crime survivors came over from the U.K. in the 1960s, the idea was that the government’s shortcomings in protecting its citizens from the conditions that exacerbate violence made it the collective responsibility of the government to address.

Unlike some legislation that uses tax dollars to help combat the problem, though, the federal dollars that support victims of violent crime go up and down every year, depending on the fines and fees collected from the prosecution of crime, white-collar crime in particular. In other words, the amount of funding to support crime victims across the country depends on more crime taking place.

“Victims of crime, in the current way that the funding apparatus works, need corporations to do bad things,” Levine said. “It needs people to be convicted of crime at misdemeanor level, at felony level, at the corporate white collar level. That’s how it’s set up. I don’t think that’s right. I think the incentives are perverse. I think it incentivizes more crime, which makes, to me, really contradictory aims.”

This model for funding crime survivors operates in contrast from how other nations, particularly in Europe, fund victim compensation. Programs in countries like the U.K., Sweden, and France are supported by public funds. While the idea that those incriminated should be fined to provide restitution made sense to some at the time, the math hasn’t added up to enough to properly fund victim compensation. Attempts to change the fining model over the years to boost available funds haven’t worked, Levine said.

Funding for victim compensation has been dwindling federally, to nearly $3.3 billion in 2024, down 75% from its peak of $13 billion in 2017. Not many know about the program or apply: During the 2023 fiscal year, only 8,994 New Yorkers applied for victim compensation and 5,467 were approved, with payments at just over $18 million to those New York residents. For context, in the same fiscal year, the NYPD nearly doubled its overtime budget of $370 million, according to the comptroller’s office, projecting that they’d spend more than $700 million. The difference in spending is estimated to be 20 times what the state spent on victim compensation.

A recent poll by the Alliance for Safety and Justice estimated that 96% of crime survivors nationwide don’t get victim compensation. What’s more, the application processing is plagued by racial bias: Reporting from the AP found that nationally, Black applicants make up less than half of compensation applications but 63% of denials, according to an Alliance investigation of 23 states. Denial rates for Black applicants tended to be for “subjective” rather than “administrative” reasons.

While New York’s denial rates for white and Black residents aren’t far apart, steps like requiring a police report within a week of the crime are hurdles that keep many Black New Yorkers from proceeding.

The trajectory for crime survivors changes dramatically when financial support is available. Survivors are less likely to develop post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental health conditions when they are able to cover the costs that follow their victimization. Without financial support, survivors are often left with devastating results, such as losing their jobs, substance use, developing an over-reliance on emergency rooms to manage pain and suffering, and even cycling through jail and prison. Supporting and stabilizing crime survivors can reduce the costs of violence and even prevent gun violence, reducing its burden on society and state and local governments.

The state recently passed the Fair Access to Victim Compensation bill, a law removing the requirement for a police report to get compensation, although it will not be enacted until December 2025. “The main crux is that it would remove the police report requirement, and it would expand the types of evidence that survivors can use to show the Office of Victim Services that a crime has occurred,” said Tahirih Anthony, senior policy manager at Common Justice, an advocacy organization that campaigned for the bill. “This could be a victim service provider. This could be a licensed medical and mental health provider.”

The act also changes the amount of time for a survivor to file a claim from one year to three years, Anthony said, which opens the opportunity for people like Peggy Herrera to file a claim for her son’s death. This extended time range is important for victims.

“Through working with survivors, you realize that healing just isn’t linear. Everyone isn’t ready to start doing paperwork when they’re going through some of their darkest days,” Anthony said.

Despite the reforms to application requirements, people can still be barred from receiving victim compensation if they are deemed to have contributed to their crime, in a stipulation in the state law known as contributory conduct.

“If you’re a victim of crime and the police officer who takes the report says that they think that you were a rival gang member and that’s why it happened, or says they think that you started it, your compensation application can be fully denied, or vastly reduced, just based on that allegation,” said Danielle Sered, executive director of Common Justice.

OVS spokesperson Kava said that reducing or denying claims due to contributory conduct has been a rare occurrence in the past six years. Between 2018 and 2023, she said, 222 claims have been reduced and 19 claims have been denied due to contributory conduct, out of a total of 55,511 claims filed.

“OVS reviews all claims in the light most favorable to the individual filing the claim, Kava said. “The agency makes all decisions, including conduct contributing determinations, solely on the actions or conduct of individuals at the time of the crime for which the claim is filed,” Kava wrote in an email.

But Sered criticized the philosophy behind denying aid to those deemed responsible for their injuries, especially because many perpetrators of harm have been exposed to harm themselves.

“It reflects a broader belief that we think there are some people who don’t deserve care; where, even if they’re hurt, their pain doesn’t matter to us. It’s not important to us anymore,” she said.

Common Justice is working on legislation to remove the contributory conduct stipulation and increase access to the program, having successfully campaigned for a state law that eliminates the requirement that applicants report their crime to police. But Sered said that in an ideal world, gun violence survivors wouldn’t need to rely on victim compensation to support themselves financially.

Creating supportive circles

Peggy, Gwen, Janifer, and Monica recently met in Peggy’s yard. Some of them wore black vests with pictures of their children and white printed numbers: birthdays, death days. They are part of Not Another Child, a support organization founded by Oresa Napper-Williams that provides a support system for survivors of gun violence. They know from experience exactly what their peers need, from help with funeral arrangements, memorial services, and crime victim compensation applications to peer support sessions and retreats.

“She gives me the strength to be a better me every day,” Cassaberry said of Napper-Williams.

Reflecting on the needs that go unmet for survivors, Napper-Williams said, “The priority should be to get us the funding to do the work.”

Not Another Child, Napper-Williams, and the organization’s work to meet survivor needs has gotten the attention of the White House on the importance of community-based victim support organizations.

Napper-Williams envisions Not Another Child offering temporary housing to immediately relocate survivors of violence, but building support systems for survivors is difficult with the delays in getting the public funds they are allocated, like the $35,000 and $25,000 discretionary pay from the city that she received months after their completed contract. She feels that organizations like hers are better suited to meet the needs of victims than government.

“NYPD gets their money upfront. We do the work on a reimbursable contract most of the time.”

These women know that support that’s sensitive to survivor needs, such as check-ins, funds to support their children in the short term, aid with housing and relocation, is what many others need to to get to healing.

“I tell people, it took pain to heal pain for my own life,” Herrera said. “I just want, when someone goes through that, they can heal from their pain, but that it wouldn’t keep them stuck… they will go out and help somebody heal from their pain.”

____

Blacklight Investigative Reporter Shannon Chaffers contributed to reporting this story.

Like this:

Like Loading…

Related

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66fe1f99ea5d47788e255ef5a58678fd&url=https%3A%2F%2Famsterdamnews.com%2Fnews%2F2024%2F10%2F03%2Fhow-the-financial-costs-of-gun-violence-hurt-loved-ones-left-behind%2F&c=6260979464019095137&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-10-02 17:11:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.