Yvan Goll was born in 1891. In his twenties, he moved to Paris, where he wrote antiwar poetry and absurdist drama, met Picasso and Chagall, and gorged himself on the era’s avant-garde buffet. Photographs show us a laser-eyed face that is either wrapping up a sneer or embarking on a new one. He looks like the kind of person who would pen an attack on the young rascals who called themselves Surrealists, and, in 1924, he did. By making “Freud a new muse,” Goll wrote, Surrealists were “confusing art and psychiatry,” producing glib, trivial work that strained to “shock the public.” The good news was that it would “quickly disappear from the scene.” I should add that Goll considered himself a Surrealist, and that he was jabbing at his rivals’ ideas in an issue of Surréalisme, the journal he founded. You should also know that he did the jabbing days before the poet André Breton published his first Surrealist manifesto.

Let’s assume, as a flurry of exhibitions have this year, that the appearance of Breton’s manifesto, a century ago, marks the birth of Surrealism as we know it. This would mean that people have been trying to kill Surrealism since it was in the womb. Childhood was no less eventful: in 1930, members of the far-right League of Patriots interrupted a screening of Luis Buñuel’s Surrealist film “L’Âge d’Or” to drop stink bombs and throw ink at the screen, which sounds suspiciously like a Surrealist stunt itself. Still harsher assaults came from within. In 1939, Breton, in his capacity as the leader of the group he’d defined, kicked out the world’s most famous Surrealist, Salvador DalĂ, for being too flamboyant, too right-wing, and (probably) too charismatic. RenĂ© Magritte, maybe the most famous Surrealist not named DalĂ, left to found his own spinoff. In 1968, pirate-costumed Yippies gathered outside MOMA to celebrate Surrealism and protest the lobotomized version trapped inside.

The paradox is that these endless attacks didn’t ruin things; they seem to have made Surrealism indestructible, free to spread wherever it pleases. The screechy orange in “The Elephants” must have been a sight to see in 1948, when Dalà painted it, but now anybody can find it in the sky when California or Canada is on fire, or in the hair of the forty-fifth President, or on the Sphere, in Las Vegas, when it turns into a giant jack-o’-lantern. Illogic and uncanniness barely require pointing out; social media is a chorale of non sequiturs, and, for long chunks of the pandemic, time was measured by the melting-watch minutes of “The Persistence of Memory.” Only one kind of art has been whisked into the batter of our world until it flavors everything.

But every kind of art, like every kind of person, has its own unconscious—its own primal memories and guilty ambitions. Because Surrealism has always worn its nightmares on its sleeve, it can be hard to imagine anything else underneath. A snippet from Goll, the Surrealist leader who wasn’t, comes to mind, though: “Reality is the basis of all great art. Without it there is no life, no substance.” Much of art depicts a world we know and hints at the otherworldly. What if Surrealism, beneath the burning giraffes and furry teacups, has always dreamed of waking up?

Let me begin by throwing some ink of my own: the first Surrealist manifesto—Breton’s, not Goll’s—is a triumph of tediousness. I am not alone in feeling this way. “It’s actually a very boring document,” the novelist Tom McCarthy said, speaking on behalf of the countless arty teen-agers who’ve fallen in love with DalĂ, looked up the text that inspired him, and lost interest by page 2. Those who stick with it will find Breton defining Surrealism as “psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express . . . the actual functioning of thought,” and vowing to resolve dreams and waking life by restoring a sense of “the marvelous” to the latter. The movement owed lots to the Dadaist artists who emerged during the First World War, and who pledged themselves to nonsense as fervidly as wise, levelheaded civilization had pledged itself to mass slaughter. It owed at least as much to Freud, whose work Breton had studied as a young medical student, and to the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who coined the term in 1917 but graciously left most of the explaining to others.

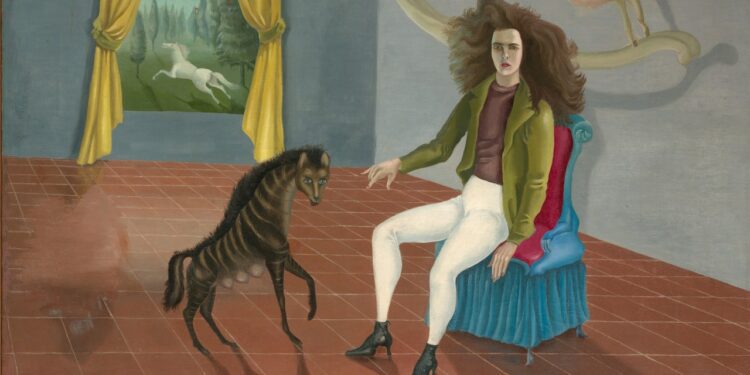

At first, words held more sway over Surrealism than images did, but within a few years artists of all stripes had joined up. The movement’s devotion to the pleasure principle can’t have hurt, and soon it had constructed a series of monuments to its own drooly libido: Man Ray’s photographs of Lee Miller; Max Ernst’s chimeric nudes; most of DalĂ. Same-sex desire, you can deduce from this list, was low among the freedoms Breton sought to celebrate—he accused male homosexuals of “mental and moral deficiency.” Female Surrealists fared somewhat better, though the most talented ones were often conscripted into being their husbands’ muses.

The exalted subconscious, the spurning of reason—these are the precepts of Breton’s manifesto, familiar from any art-history textbook. What the textbooks rarely report is that he begins by dunking on Dostoyevsky—specifically, a short description of a room from “Crime and Punishment.” The room is small, and outfitted with yellowish furniture, yellow wallpaper, muslin curtains, and geraniums in the windows. That’s it, more or less; the writing isn’t great, but far from terrible. To Breton, however, this passage demonstrates what’s so wretched about realism in art: it dares to wallow in everyday reality, the stuff that he calls “the empty moments of my life.” All avant-gardes need a devil. Surrealism, via faith in the id’s boundless originality, was meant to save our souls from endless stacks of “school-boy description,” so clichéd that Dostoyevsky could have taken them from “some stock catalogue.”

It is hard to trust a writer who hates Dostoyevsky, let alone one who thinks that the author of “The Grand Inquisitor” wrote realist Mad Libs. But Breton was an odd duck, forever flitting between polemic and clenched restraint: apparently, the man who trumpeted the aesthetics of louche, feral freedom had no taste for drugs, brothels, or staying out late. Even in his heyday, when his charisma could vaporize entire careers, fellow-Surrealists mocked his primness—he insisted on kissing women on the hand, a custom only slightly hipper a century ago than it is today. Still, someone had to drive the bus. In “Why Surrealism Matters” (Yale), published earlier this year, Mark Polizzotti does an elegant job of defending Breton, as well he might, having also authored a seven-hundred-page biography of the poet. “We have to wonder,” he writes, “whether Breton’s tendency to hold back was precisely what allowed him to sustain the Surrealist group for almost half a century, and to ensure its legacy.”

Pluck this man out of Surrealism’s history, and he takes plenty with him. Yes, Breton did too much plucking himself—not just Dalà but Antonin Artaud, Georges Bataille, and other mutinous geniuses—and, yes, he wasted years on a merger with the Communist Party that, with the benefit of hindsight, seems doomed from Day One. But he evangelized as much as he excommunicated. One of the explicit aims of the Met’s 2021 mega-survey “Surrealism Beyond Borders” was to tell a story of a global movement without Breton (or anyone else) at the center, but it left him looking more central than ever: the Johnny Appleseed of id art, spreading it to Mexico and Martinique, lecturing on it in New Haven and Port-au-Prince, and rousing the great Chicago Surrealist Ted Joans to undertake a pilgrimage to Paris, where the two men bumped into each other at a bus stop.

Central doesn’t have to mean most important. In this case, it may not even mean most coherent. The complaint is often made that what we now call surreal has been watered down to the point of senselessness, as though it were once a strict, bulleted ideology, when the fact is that Surrealism was always a sly combination of specific and vague. In his biography, Polizzotti praises Breton’s manifesto for making Surrealism sound both woozy and clinical, arming it with the double authority of the poet and the doctor. Goll had already pointed out that these two didn’t go together; his mistake was to assume that this was a weakness instead of the beguiling imperfection that inspired a century of riffs and revisions.

Examining Surrealist art, one is often relieved that Breton never decided exactly what it was. Have another look at his definition—how would it even work for visual art? Can any painting evince pure psychic automatism? An abstract splatter, maybe, except that Breton had trouble admitting that abstraction could be Surrealist. And yet Surrealism, like the Roman Empire or Amazon, had an extraordinary knack for absorbing its dissenters. The finest thing in “Surrealism Beyond Borders” may have been a painting by the Ethiopian Armenian artist Skunder Boghossian, “Night Flight of Dread and Delight” (1964), which shows a bird fluttering over a landscape, its eyes two more celestial bodies in a sky ready to burst with them. The paradox (Surrealism, you’ll have noticed, is all paradoxes) is that this image’s dreamy, figurative bits may well be its least surreal—my eyes always sink to the lower right-hand corner, where the frenzy of dots becomes totally, gleefully abstract. This isn’t the Surrealism that Breton prescribed; it’s far more surreal than that, too sloshed on the sheer possibilities of paint to care whether it’s staying true to psychic automatism. Half of all writers, per the old joke, try to imitate Hemingway, while the other half try not to. Surrealism’s trick was to jolt painters like Boghossian into embracing its tenets and moving past them on the same canvas.

Surrealism’s contradictions burn hottest in paintings, which make up the better portion of one of the year’s major centennial shows, “IMAGINE! 100 Years of International Surrealism.” I saw it at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts, in Brussels, but it will move to Paris, in September, and after that to Hamburg, Madrid, and Philadelphia, shedding and gaining works along the way. The Brussels curators were as shamelessly European in their selections as the Met’s were doggedly international, featuring a group of largely canonical names and classifying their creations by motif: the forest, the labyrinth, and so on.

There is a dryness to much Surrealist art, as though a hallucination were being recounted in monotone. One virtue of “IMAGINE!” was its attention to this quality, putting Surrealism side by side with its kooky uncle, Belgian Symbolism, the fin-de-siècle aesthetic of Jean Delville, Fernand Khnopff, and William Degouve de Nuncques, all of whom delighted in depicting mythic figures and objects with a shimmery mystery that can come off as merely schlocky. De Nuncques’s “The Enchanted Forest” (1896) is all glow and shadow, hinting at some vast secret. Surrealist treatments of the same subject, like “Landscape,” Magritte’s sylvan scene from 1927, or “Undergrowth,” André Masson’s from a few years earlier, hold less back: the secrets arrive in broad daylight, one frank brushstroke at a time. Stylistic peacockery in general is rarer than you might expect—walking through the exhibition, I wasn’t often struck by a provocative color contrast, a virtuosic line, a deft impasto patch. The “how” of these images steals very few scenes from the “what.”

As for the “what”: to the best of my recollection, I have never dreamed about the desert, even though I spent the first eighteen years of my life in one. I say this because the Surrealists sometimes appear to have dreamed about little else. Psychic automatism is a dubious technique but a splendid alibi, enabling many of the artists in the exhibition to get away with imagery that, if not outright clichĂ©, looks a lot like it. In “The Women’s Uprising” (1940), Rita Kernn-Larsen gives trees breasts and curvy hips; tree-women also star in paintings by MĂ©ret Oppenheim and Paul Delvaux, though they’re perhaps slightly outnumbered by all the bird-women, and both are severely outnumbered by the deserts. Once you start to notice these, it is hard to stop. Poetically barren landscapes—gravelly in front, mountainous in back, tired all over—figure in paintings by Delvaux, DalĂ, Marion Adnams, and Yves Tanguy, and also Ramses Younan and Adnan Muyassar, if we count the Met show. Freud got many things wrong, but projection wasn’t one: Surrealism, which talked so tough about realism’s silly conventions, ended up with enough of its own that they may as well have been—how should I put this?—taken from some stock catalogue.

The marvellous, to be fair, is a tricky thing to promote. The more successful the promoting, the less marvellous the results. Everybody knows this from living in the current millennium, but “IMAGINE!” provides a concentrated refresher: most of its wonders come fast and fade faster, disrupting nothing but one another. I’ve had a similar feeling while messing around with DALL-E, the Surrealist-named A.I. system that translates text descriptions into glassy images. It’s miraculous, and boring in its miracles—the ease with which the technology vomits up content exactly mirrors the ease with which I get weary of it. Maybe I’m ungrateful, or maybe the id gets tedious when invited to speak too freely. Call this the deepest paradox of Surrealism: the voice of the unconscious, whether babbling away in comments sections, ads, or Presidential debates, is the dullest one on the planet.

Surrealism can take a few hits, probably needs them. Chisel away what’s lacklustre, and you are left with the good, more lustrous than ever. The final galleries of “IMAGINE!,” devoted to the motif of the cosmos, attempt to end the story with a flourish. They don’t, and the problem has nothing to do with curation.

“Instead of creating a magical world,” the onetime Surrealist Barnett Newman wrote, “the Surrealists succeeded only in illustrating it.” Fair enough, but only if you accept that their goal was to find wonder in galaxies, or to fill landscapes with flying apples and tiny trains. These were the sorts of things that first attracted me, like so many others, to Magritte’s paintings. When I look now, I’m indifferent to the obviously surreal bits but awed by the ordinary, utilitarian realities—the streets, the bowler hats, the neat bourgeois interiors. On the surface, it’s perplexing that plain, unadorned tobacco pipes show up in so many Surrealist works: Magritte’s paintings of pipes that aren’t, of course, as well as Man Ray’s photographs and the wooden boxes of bric-a-brac assembled by Joseph Cornell. But have you ever seen—really, deeply seen—a pipe? I’m not sure I had before getting acquainted with the various examples in Cornell, none of which will ever tar a set of lungs again. Pale, lopsided creatures, they have nothing to do anymore but occupy their corners of Cornell’s zoo. To seem surreal, mundane things don’t need to be transformed, exactly, just allowed to breathe.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66b0a45cf2e441099e23bf0a6d8c3804&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.newyorker.com%2Fmagazine%2F2024%2F08%2F12%2Fthe-bad-dream-of-surrealism&c=16925158379701480452&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-08-04 13:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.