Temperature

In January 2024, the NOAA Global Surface Temperature (NOAAGlobalTemp) dataset version 6.0.0 replaced version 5.1.0. This new version incorporates an artificial neural network (ANN) method to improve the spatial interporlation of monthly land surface air temperatures. The period of record (1850-present) and complete global coverage remain the same as in the previous version of NOAAGlobalTemp. While anomalies and ranks might differ slightly from what was reported previously, the main conclusions regarding global climate change are very similar to the previous version. Please see our

Commonly Asked Questions Document

and

web story

for additional information.

NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information calculates the global temperature anomaly every month based on

preliminary data generated from authoritative datasets of temperature observations from around the globe. The major

dataset,

NOAAGlobalTemp version 6.0.0,

updated in 2024, uses comprehensive data collections of increased global area coverage over both

land and

ocean surfaces. NOAAGlobalTempv6.0.0 is a reconstructed dataset,

meaning that the entire period of record is recalculated each month with new data. Based on those new calculations,

the new historical data can bring about updates to previously reported values. These factors, together, mean that

calculations from the past may be superseded by the most recent data and can affect the numbers reported in the

monthly climate reports. The most current reconstruction analysis is always considered the most representative and

precise of the climate system, and it is publicly available through

Climate at a Glance.

Note: Information from Environment Canada summarizing conditions in Canada for the spring and year-to-date periods was added to this report on June 14, 2024.

May 2024

The May global surface temperature was 1.18°C (2.12°F) above the 20th-century average of 14.8°C (58.6°F), making it the warmest May on record. This was 0.18°C (0.32°F) above the previous record from May 2020. May 2024 marked the 48th consecutive May (since 1977) with temperatures at least nominally above the 20th-century average.

May had a record-high monthly global ocean surface temperature for the 14th consecutive month. El Niño conditions that emerged in June 2023 were replaced by ENSO-neutral conditions during the past month, and according to NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center La Niña is favored to develop during July-September (65% chance) and persist into the Northern Hemisphere winter 2024-25 (85% chance during November-January).

The Northern Hemisphere also ranked as the warmest May on record at 1.44°C (2.59°F) above average. The Northern Hemisphere land temperature was also record warm in May (tied with 2020) and the ocean temperature was again record-high by a wide margin (0.25°C/0.45°F warmer than the previous record set in 2020). The Arctic region had its 11th warmest May on record.

May 2024 in the Southern Hemisphere also ranked warmest on record at 0.92°C (1.66°F) above average. The ocean-only temperature for May in the Southern Hemisphere ranked highest on record, while the land-only Southern Hemisphere temperature was 6th warmest on record. Meanwhile, the Antarctic region had its 23rd warmest May, 0.55°C (0.99°F) above average.

A smoothed map of blended land and sea surface temperature anomalies is also available.

Record warm temperatures covered large parts of the African continent, northern China and Mongolia, areas neighboring the North Sea, and many parts of a region stretching from southern Brazil northward through most of Mexico. A prolonged heatwave brought numerous all-time record high temperatures in Mexico, which is also enduring widespread drought, leading to dozens of fatalities and numerous wildlife deaths.

Temperatures were warmer to much-warmer-than-average across much of the Arctic, the eastern U.S. and large parts of Canada, western Europe, the eastern half of Russia, southeast Asia, and much of Australia. In northern and central India and Pakistan, where temperatures for the month as a whole were warmer to much-warmer-than-average, a severe and persistent heat wave struck during the last half of the month. Temperatures in excess of 48°C (118°F) occurred in many locations in India, resulting in strained water supplies and many deaths. Temperatures at or above 52°C were reported in Pakistan and a daily high temperature of 52.0°C (125.6°F) was recorded at Shahbaz AB, Jacobabad, Pakistan on May 26 as found in NCEI’s GHCN-Daily dataset. For the month of May as a whole, 22 days exceeded 45°C (113°F) at that location, and in other places daily high temperatures exceeded 40°C (104°F) numerous times in May.

In contrast, cooler-than-average temperatures covered areas that included western parts of Russia and Kazahkstan, much of the western U.S. and Alaska, and large parts of Greenland. May temperatures were also cooler-than-average in Argentina and Chile, where a succession of polar air masses brought the strongest cold wave in more than 70 years to parts of Chile.

Across the global oceans, record warm sea surface temperatures covered much of the tropical Atlantic and large parts of the Indian Ocean and the equatorial western Pacific as well as parts of the southwest Pacific and Southern Ocean. Record warm temperatures also occurred in the North Sea and neighboring seas in the North Atlantic. Positive anomalies also covered large parts of the northern Pacific. Record-warm temperatures covered approximately 16.1% of the world’s surface this May, which was the highest percentage for May since the start of records in 1951, and 11.2% higher than the previous May record of 2016.

Near-average to cooler-than-average temperatures covered large parts of the southeast Pacific, the southwest Atlantic, areas of the southwest Indian Ocean, and parts of the Southern Ocean. Only 0.2% of the world’s surface had a record-cold May.

Africa had its warmest May on record while North America had its fifth warmest, Europe its third warmest, and South America its 11th warmest May.

The United Kingdom experienced its warmest May on record, in a series dating back to 1884, with a mean temperature 2.4°C above average, based on preliminary data.

Germany had its second warmest May since 1901, 1.9°C warmer than the 1991–2020 average.

May 2024 was relatively warm in Austria, 1.0°C above the 1991–2020 average in the lowlands of Austria and 0.6°C above average in the mountains region, both the 28th warmest in series that date back 258 years and 174 years, respectively.

MeteoSwiss reported that this May was 0.1°C below the 1991–2020 average for Switzerland, as temperatures were influenced by the wettest May conditions in 60 years of records.

The contiguous U.S. had its 13th warmest May in the 130-year record, tying 1941 and 2007.

The Caribbean Islands region had its warmest May on record, a remarkable 0.63°C (1.13°F) warmer than the previous record warm Mays of 2016 and 2020.

The Main Development Region for hurricanes in the Atlantic also had its warmest May on record, 0.37°C (0.67°F) warmer than the previous record warm May of 2010.

May 2024 ranked ninth warmest for Asia and Oceania tied as sixth warmest on record for May.

Japan had its seventh warmest May since statistics began in 1898, 0.67°C above the 1991–2020 average.

According to the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, Australia’s national area-averaged mean temperature was 0.99°C above the 1961–1990 average, the 17th warmest May since records began in 1910.

New Zealand had its coldest May in 15 years, 1.3°C below the 1991–2020 average, according to New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research.

May Ranks and RecordsMayAnomalyRank

(out of 175 years)Records°C°FYear(s)°C°FGlobal+1.63+2.93Warmest1st2024+1.63+2.93Coolest175th1867-1.11-2.00+0.98+1.76Warmest1st2024+0.98+1.76Coolest175th1911-0.51-0.92+1.18+2.12Warmest1st2024+1.18+2.12Coolest175th1917-0.51-0.92Northern Hemisphere+1.79+3.22Warmest1st2020, 2024+1.79+3.22Coolest175th1867-1.49-2.68Ties: 2020+1.18+2.12Warmest1st2024+1.18+2.12Coolest175th1917-0.55-0.99+1.44+2.59Warmest1st2024+1.44+2.59Coolest175th1907-0.66-1.19Southern Hemisphere+1.28+2.30Warmest6th2002+1.78+3.20Coolest170th1874-1.43-2.57+0.84+1.51Warmest1st2024+0.84+1.51Coolest175th1904-0.50-0.90+0.92+1.66Warmest1st2024+0.92+1.66Coolest175th1874, 1911-0.53-0.95Antarctic+0.55+0.99Warmest23rd1983+1.65+2.97Coolest153rd1943-1.23-2.21Ties: 2012Arctic+1.79+3.22Warmest11th2019+2.59+4.66Coolest165th1867-2.52-4.54

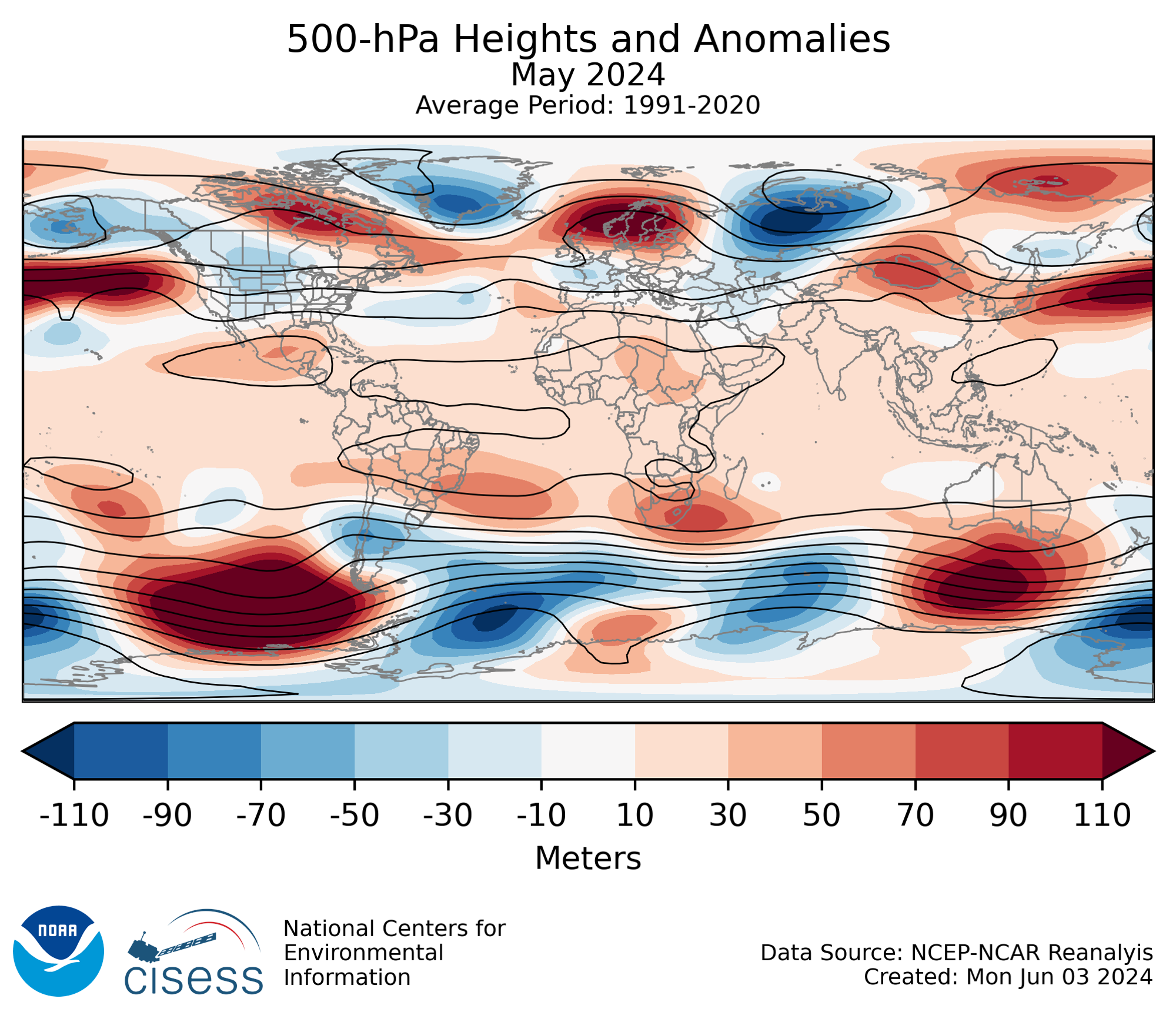

500 mb maps

In the atmosphere, 500-millibar height pressure anomalies correlate well with temperatures at the Earth’s surface.

The average position of the upper-level ridges of high pressure and troughs of low pressure—depicted by

positive and negative 500-millibar height anomalies on the map—is generally reflected by areas of positive and

negative temperature anomalies at the surface, respectively.

Seasonal Temperature: March –May 2024

The March 2024–May 2024 global surface temperature was the warmest March–May period in the 175-year record, 1.29°C (2.32°F) above the 20th-century average of 13.7°C (56.7°F). The past eleven March–May periods have ranked among the twelve warmest such periods on record.

The March–May period is defined as the Northern Hemisphere’s meteorological spring and the Southern Hemisphere’s meteorological fall. The Northern Hemisphere spring 2024 temperature was also the warmest on record, and marks the 48th consecutive spring with global temperatures nominally above the 20th-century average in the Northern Hemisphere. The Southern Hemisphere fall temperature also ranked warmest on record, and also marks the 48th consecutive warmer-than-average fall in the Southern Hemisphere.

March–May Ranks and RecordsMarch–MayAnomalyRank

(out of 175 years)Records°C°FYear(s)°C°FGlobal+1.92+3.46Warmest2nd2016+1.93+3.47Coolest174th1867-1.07-1.93+1.00+1.80Warmest1st2024+1.00+1.80Coolest175th1911-0.49-0.88+1.29+2.32Warmest1st2024+1.29+2.32Coolest175th1917-0.56-1.01Northern Hemisphere+2.25+4.05Warmest2nd2016+2.32+4.18Coolest174th1867-1.28-2.30+1.16+2.09Warmest1st2024+1.16+2.09Coolest175th1917-0.54-0.97+1.63+2.93Warmest1st2024+1.63+2.93Coolest175th1917-0.71-1.28Southern Hemisphere+1.17+2.11Warmest3rd2002+1.35+2.43Coolest173rd1917-0.84-1.51+0.89+1.60Warmest1st2024+0.89+1.60Coolest175th1911-0.51-0.92+0.94+1.69Warmest1st2024+0.94+1.69Coolest175th1911-0.53-0.95Antarctic+0.21+0.38Warmest41st1980+0.95+1.71Coolest135th1960-0.79-1.42Arctic+2.35+4.23Warmest10th2019+3.43+6.17Coolest166th1867-1.98-3.56

Over the land surface, air temperatures for the season were record warm across most of central and northern South America, Central America and Mexico, much of Africa, and large parts of Europe, China, and Southeast Asia. Elsewhere, seasonal temperatures were much-above-average across much of the eastern half of Asia, the eastern U.S. and Canada, northern Canada and much of the Arctic.

In contrast to the widespread anomalous warmth, areas with March–May seasonal temperatures cooler than the 1991–2020 average included the western half of the contiguous U.S., areas of southeastern Greenland, southern Argentina and Chile, western areas of Russia and northern Kazakhstan, Afghanistan and parts of neighboring countries, and parts of Australia and the eastern half of Antarctica.

Sea surface temperatures for the March–May period were record warm across much of the tropical Atlantic, eastern tropical Pacific, areas of the southern Atlantic, and parts of the Indian Ocean and western Pacific. Areas with seasonal sea surface temperatures cooler than the 1991–2020 average included the southeastern Pacific Ocean, the southwest Atlantic, southwest Indian Ocean, and parts of the Southern Ocean.

A smoothed map of blended land and sea surface temperature anomalies is also available.

Europe recorded its warmest spring on record at 2.45°C (4.41°F) above the 20th century average. Africa’s March to May period also ranked warmest, 2.04°C (3.67°F) above average.

Germany had its warmest spring since national records began in 1881, 2.0°C above the 1991–2020 average.

Austria also had its warmest spring on record. The lowlands of Austria were 1.9°C above the 1991–2020 average, and the mountain region was 1.6°C above average, based on preliminary data from GeoSphere Austria.

Switzerland had its seventh-warmest spring since records began in 1864, 0.8°C above the 1991–2020 average.

South America (1.71°C; 3.08°F above average) had its warmest March–May while North America (1.94°C; 3.49°F above average) was third warmest for the season.

According to Environment Canada, based on preliminary data, Canada had its fourth warmest spring in a national record dating back to 1948, 2.5°C above normal. All provinces and territories were warmer than normal with six jurisdictions in the eastern half of the country registering within the top five of their warmest spring seasons including Quebec, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Nunavut.

The spring 2024 season in the contiguous U.S. tied 2016 as the 6th warmest on record, 1.53°C (2.75°F) above the 1901–2000 average.

The Caribbean Islands region had its warmest spring on record, 0.45°C (0.81°F) warmer than the previous record warm spring of 2020.

In the Gulf of Mexico the March–May spring season was its third warmest on record, and the Main Development Region for hurricanes in the Atlantic was record warm.

Asia had its fourth-warmest March to May (2.24°C; 4.03°F above average) and Oceania its 13th warmest for the 3-month period (0.91°C; 1.64°F above average).

In Japan, this spring was the third warmest since statistics began in 1898, 1.22°C above the 1991–2020 average.

In Australia, the national mean temperature for autumn was 0.53°C above the 1961–1990 average, the 23rd-warmest on record.

According to New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) autumn in New Zealand was the coolest since 2012 and the fourth-coolest since 2000, 0.6°C below the 1991–2020 average, as generally persistent southwesterly winds brought cooler-than-average seasonal temperatures to the country.

Year-to-date Temperature: January–May 2024

The January–May global surface temperature was the warmest in the 175-year record at 1.32°C (2.38°F) above the 1901-2000 average of 13.1°C (55.5°F).

January to May was characterized by much-warmer-than-average to record-warm conditions across many parts of the globe. Record warm temperatures covered much of northern and central South America, Central America, southern Mexico, large parts of Africa, central and western Europe, and parts of China and Southeast Asia. Widespread areas of warmer to much-warmer-than-average conditions were present in the eastern U.S. and Canada, across much of the Arctic, large parts of Asia, and western Antarctica. Anomalies in excess of 3°C (5.4°F) were widespread in eastern and northern Canada and the Arctic.

In contrast, near to below-average January-May temperatures covered most of the western U.S. to Alaska, eastern Greenland, much of western Russia and the Russian Far East, parts of India, some areas of northern Australia, and much of eastern Antarctica.

Sea surface temperatures for the January–May period were above average to record-warm across much of the tropical and northeastern Atlantic Ocean, much of the northern, western, and equatorial Pacific Ocean as well as large parts of the Indian Ocean. Sea surface temperatures for the five-month period were near to below average over the northwestern Atlantic Ocean, the southwestern Atlantic, the southeastern Pacific, parts of the Southern Ocean, and the southwestern Indian Ocean.

A smoothed map of blended land and sea surface temperature anomalies is also available.

South America, Europe, and Africa each had their warmest January–May periods on record. North America had its second-warmest January–May on record while Asia was eighth-warmest and Oceania tied 1998 as fifth-warmest.

According to Environment Canada, based on preliminary data, Canada had its third warmest January–May period in 2024 at 3.1°C above normal, in a national record dating back to 1948. Eastern Canada was especially warm with all jurisdictions within the top four of their warmest January–May periods including Ontario, Quebec, all Atlantic Canada provinces, and Nunavut in the north.

In the contiguous U.S. the January–May 2024 period was the fifth warmest on record, 1.9°C (3.4°F) above the 1901–2000 average.

January–May Ranks and RecordsJanuary–MayAnomalyRank

(out of 175 years)Records°C°FYear(s)°C°FGlobal+1.98+3.56Warmest2nd2016+2.06+3.71Coolest174th1862, 1867-0.94-1.69+1.02+1.84Warmest1st2024+1.02+1.84Coolest175th1911-0.48-0.86+1.32+2.38Warmest1st2024+1.32+2.38Coolest175th1917-0.57-1.03Northern Hemisphere+2.37+4.27Warmest2nd2016+2.52+4.54Coolest174th1867-1.11-2.00+1.18+2.12Warmest1st2024+1.18+2.12Coolest175th1917-0.53-0.95+1.69+3.04Warmest1st2024+1.69+3.04Coolest175th1862, 1917-0.68-1.22Southern Hemisphere+1.09+1.96Warmest1st2024+1.09+1.96Coolest175th1861-0.80-1.44+0.90+1.62Warmest1st2024+0.90+1.62Coolest175th1911-0.49-0.88+0.94+1.69Warmest1st2024+0.94+1.69Coolest175th1904-0.51-0.92Antarctic+0.00+0.00Warmest77th1980+0.76+1.37Coolest99th1960-0.64-1.15Ties: 1938, 1944Arctic+2.70+4.86Warmest6th2016+3.75+6.75Coolest170th1966-2.07-3.73

Precipitation

The maps shown below represent land-only precipitation anomalies and land-only percent of normal precipitation based on the GHCN dataset of land surface stations.

May 2024

Above-average May precipitation occurred across large parts of western and central Europe, central Asia, far northeastern China, Korea, and Japan. Other wetter-than-average areas included the southern half of India, central Australia, and much of the Seychelles and Mauritius. Precipitation was below average in the southwestern U.S., Mexico, Central America, much of Brazil and Argentina, and much of eastern Europe. Other areas with widespread drier-than-average conditions included much of the United Kingdom, Spain and neighboring parts of Morocco and Algeria, northern India and neighboring Pakistan and Afghanistan, eastern China, southern and western areas of Australia, and many islands of the South Pacific.

In Germany, precipitation for May was 69.2% above the 1991–2020 average, the third wettest May since 1881. In some areas precipitation for the month was more than three times above average, and flooding occurred in the western areas of Saarland and Rhineland-Palatinate. Flooding also occurred in other parts of southern Germany late in the month that led to dam breaks, extensive damage to buildings and agriculture, and loss of life.

Heavy rains led to flash flooding in Afghanistan with the most severe impacts in northern areas of the country. More than 300 people died and thousands of homes were destroyed. Heavy rains later in the month led to additional damage and loss of life.

The United Kingdom had a wetter-than-average May, recording a provisional 82.5mm of rain (116% of the average May rainfall). Much of this was concentrated in northern England, which had 155% of its average May rainfall.

In Switzerland it was the wettest May since measurements began more than 60 years ago. Heavy rainfall at the end of the month led to flooding in eastern Switzerland.

Austria had one of the 15 wettest Mays since national records began in 1858, with 41% more precipitation than the 1991–2020 average.

According to the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, for Australia as a whole, the area-averaged rainfall total for May was 34.9% below the 1961–1990 average.

Drought in May

Drought information is based on global drought indicators available at the

Global Drought Information System website,

and media reports summarized by the National Drought Mitigation Center.

May Overview:

GDIS global indicators revealed a mix of precipitation anomalies in May 2024. Wet (above-normal) conditions brought limited relief to some drought areas across the world, especially Canada, Southwest Asia, and southern parts of Central America, but the month was dry in parts of Africa, Australia, South America, northern and eastern Europe, and South Asia, with warm temperature anomalies dominating. The precipitation that fell was not enough to make up for months, even years, of deficient precipitation.

Southern Africa experienced the driest May and second driest January-May, while the entire continent of Africa had the fourth driest May and warmest May through June-May (all 12 time periods).

South America has been plagued by record heat and dryness for several months to years — while May 2024 ranked 11th warmest and 30th driest, the continent still had the warmest April-May through June-May (all 11 time periods) and driest June-May (12-month period).

A significant portion of the world’s agricultural lands was still suffering from low soil moisture and groundwater levels — especially in the Americas, Africa, eastern Europe, and parts of Asia — and satellite observations showed stressed vegetation on all continents.

The GEOGLAM Crop Monitor indicated that agriculture was most threatened in parts of Central and South America, Africa, western Europe, southwest Russia, southern Australia, and southeast Asia, as well as parts of the North American Plains/Prairies.

The Famine Early Warning System Network (FEWSNet) revealed significant food insecurity continuing in parts of Central and South America, Southwest Asia, and much of Africa.

Europe:

Much of Europe was warmer than normal in May with drier-than-normal conditions across eastern Europe, Scandinavia, and the Iberian Peninsula, and wetter-than-normal conditions in between, based on the 1-month Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI). Continent-wide, Europe had the third warmest May in the 1910-2024 NOAA/NCEI temperature record and 28th wettest May in the 1940-2024 ECMWF ERA5 Reanalysis precipitation record.

Dryness is evident in the Mediterranean basin beginning at 3 months and extending in time to the 60-month time scale. At 72 months, the SPI maps showed dry conditions extending from the Mediterranean region into north-central Europe.

Much of the last year to several years were unusually warm across Europe — all ten time periods from March-May (last 3 months) back through June-May (last 12 months) were the warmest such periods in the NOAA/NCEI record. The above-normal temperatures enhanced evaporation, especially in northern and eastern Europe as seen on the 1-month Evaporative Stress Index (ESI) and Evaporative Demand Drought Index (EDDI) maps, and Europe-wide on the longer-term Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) maps.

Asia:

May was dry across western Russia; central, southern, and eastern Siberia; eastern China, and northern parts of India and Pakistan. On the other hand, Southwest Asia was wetter than normal this month.

Continent-wide, Asia had the 9th warmest and 25th wettest May in the NOAA/NCEI and ECMWF ERA5 records, respectively.

At 3 months, Southwest Asia had some dryness, which grew at 6 to 9 months; the dry areas also shifted to western China and northern India. At longer time scales (12 to 72 months), dryness intensified and expanded in Southwest Asia, expanded from northern India to Thailand, and continued across western China to Mongolia.

Africa:

Dry conditions continued in May across southern and central Africa as well as the northwest coast. May temperatures were much warmer than normal across virtually the entire continent. May 2024 ranked as the warmest and 4th driest May on record, continent-wide, with southern Africa having the driest May and second driest January-May.

The ESI and especially EDDI showed above-average evapotranspiration across almost the entire continent.

Africa has been plagued by excessive heat for several years, with all 12 time periods from May back through June-May ranking as the warmest on record for the continent, and this is reflected by excessive evapotranspiration at all 12 time scales on the EDDI maps.

The dry areas in the south, central, and northwest regions expand on the SPI maps to cover more of northern Africa at 2 to 12 months, with parts of east-central Africa wet at these time scales.

By 9 months, the driest areas on the SPI maps are South Africa and the Maghreb region, especially the northwest coast. At 24 months, wet conditions bisect the continent from east to west; the north and south become only drier at longer time scales.

When the effects of temperature (evapotranspiration) are taken into account (SPEI maps), dry conditions are more intense and cover virtually the entire continent at 1 to 12 months.

Models and satellite (GRACE) observations revealed persistent low soil moisture and groundwater in the Maghreb and adjacent western regions, and over much of central to southern Africa.

Satellite observations of vegetative health (VHI) revealed stressed vegetation over virtually the entire continent, with the most severe conditions in the north and southwest.

An analysis by the African Flood and Drought Monitor estimated 28% of the continent in drought at the end of May, which was the same as last month, and included 14 countries in drought.

Australia:

Tasmania, the northeast and southern coasts of Australia, and the western fourth of Australia, as well as much of New Zealand, were drier than normal during May, according to the SPI.

Monthly temperatures were warmer than normal in southwestern and northeastern Australia.

Dry conditions in the west, south, and northeast Australia, as well as Tasmania, persisted on the 2- to 12-month SPI maps, although not as intense in the northeast, but got more intense along the west coast at 9 to 12 months. Dryness persisted in the west and south at longer time scales, and even expanded into central Australia on the 72-month SPI map.

Dry soils were evident along the southern to southwest coast of Australia, including Tasmania, as well as New Zealand, according to GRACE soil moisture data. The GRACE data showed low groundwater in these areas and in parts of central Australia.

Satellite observations (VHI) revealed stressed vegetation across much of the continent, especially the west and southern regions, as well as parts of the east.

South America:

The May SPI map showed dry conditions across a large part of Brazil, Argentina, and Chile, with dryness extending across parts of Paraguay into Peru as well as in Venezuela. May temperatures were cooler than normal over Argentina and Chile, but much warmer than normal to the north.

Beneficial precipitation in April reduced the size of the dry areas at the 2- to 3-month time scales, but significant dryness was still visible on the SPI maps from Peru to southern Brazil. At 6 to 12 months, the dry areas intensified and expanded to cover much of Brazil, much of the northern coast of South America, and parts of southern South America. Dryness intensified and expanded in Argentina and Chile on the SPI maps at longer time scales.

Temperatures have been persistently warmer than normal for much of the continent for the last several years, with South America having the warmest April-May through June-May (all 11 time periods) in the NOAA/NCEI record.

The heat increased evapotranspiration, as seen on the ESI and EDDI maps, in central to northern South America at 1- to 3-month time scales, and across the continent at longer time scales. The increased evapotranspiration intensified and expanded the drought areas on the SPEI maps, with most of the continent severely dry at 24- to 48-month time scales.

Satellite observations (GRACE) show dry soils and low groundwater across huge swaths of South America — from the northern coast to southern Brazil, across southern Peru and Bolivia to central Argentina, and over southern Chile and Argentina.

Satellite analysis (VHI) revealed poor vegetative health in the countries along the west coast and from central Argentina to central Brazil.

According to media reports (Phys.org), a study conducted by researchers at the University of SĂŁo Paulo (USP) in Brazil and reported in an article published in Nature Communications shows that the Cerrado, Brazil’s savanna biome is experiencing the worst drought for at least 700 years.

North America:

In North America, the SPI showed May as drier than normal across most of Mexico, southern Florida; parts of the central and southwestern contiguous U.S. (CONUS) and western, southeastern, and northern Canada; as well as the northern half of Central America and parts of the Caribbean. Southern, eastern, and northern parts of North America were warmer than normal.

Unusual warmth characterized most of the last 12 months, with the periods February-May and December-May through June-May (all 8 time periods) ranking warmest on record.

The SPI maps show that dryness persisted from the southern Plains and southwestern CONUS to Central America, across western to northern Canada, and from southeast Canada to New England, at the 2- to 6-month time scales.

The SPI maps show most of Canada dry at 9 to 48 months, most of Mexico and Central America dry at 12 to 60 months, and in the U.S. — dryness across the Mississippi River Valley at 12 to 24 months, in the southern to central Plains at 24 to 48 months, and in parts of the West at 48 to 72 months.

According to NOAA/NCEI national analyses, the CONUS had the 13th warmest and 13th wettest May in the 1895-2024 record, with moderate to exceptional drought covering 12.6% of the CONUS (10.5% of the 50 states and Puerto Rico), which is less than a month ago. Moderate to exceptional drought covered 76.0% of Mexico at the end of the month, which is more than a month ago. In Canada, 20.9% of the country was in moderate to exceptional drought, and 45% was classified as abnormally dry (D0) or in moderate to exceptional drought (D1-D4), both of which are less than last month.

Satellite (GRACE) observations revealed extensive areas of low groundwater across much of western to central Canada and parts of eastern Canada, the southern Plains of the U.S. to interior Pacific Northwest, much of Mexico, and almost all of Central America. GRACE observations of soil moisture indicated dry soils across those same areas, except slightly less in Canada and the CONUS.

Satellite analysis (VHI) indicated poor vegetative health across parts of Canada and the U.S., and most of Mexico to Central America.

The North American Drought Monitor product depicted drought across the northern Rockies and Pacific Northwest, southern Florida, central Plains, and southern Plains to Southwest in the CONUS; across much of western to central Canada; and across most of Mexico.

The Caribbean Regional Climate Center SPI maps showed areas of short-term (1 to 6 months) dryness across the central to southern parts of the Caribbean Islands, and long-term (12 to 24 months) dryness over northern, central, and southern parts.

The Associated Press (AP) reported that Mexico was hit by hours of rolling blackouts in early May due to high temperatures and temporary drops in electrical power generation. Power generation also dropped unexpectedly due to other reasons including lower output from hydroelectric dams, which have been affected by drought, and clouds affecting solar power. The AP added that almost 40% of the Mexico’s dams are below 20% of capacity, and another 40% are between 20% and 50% full.

References

Adler, R., G. Gu, M. Sapiano, J. Wang, G. Huffman 2017. Global Precipitation: Means, Variations and Trends During the Satellite Era (1979-2014). Surveys in Geophysics 38: 679-699, doi:10.1007/s10712-017-9416-4

Adler, R., M. Sapiano, G. Huffman, J. Wang, G. Gu, D. Bolvin, L. Chiu, U. Schneider, A. Becker, E. Nelkin, P. Xie, R. Ferraro, D. Shin, 2018. The Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) Monthly Analysis (New Version 2.3) and a Review of 2017 Global Precipitation. Atmosphere. 9(4), 138; doi:10.3390/atmos9040138

Gu, G., and R. Adler, 2022. Observed Variability and Trends in Global Precipitation During 1979-2020. Climate Dynamics, doi:10.1007/s00382-022-06567-9

Huang, B., Peter W. Thorne, et. al, 2017: Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature version 5 (ERSSTv5), Upgrades, validations, and intercomparisons. J. Climate, doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0836.1

Huang, B., V.F. Banzon, E. Freeman, J. Lawrimore, W. Liu, T.C. Peterson, T.M. Smith, P.W. Thorne, S.D. Woodruff, and H-M. Zhang, 2016: Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature Version 4 (ERSST.v4). Part I: Upgrades and Intercomparisons. J. Climate, 28, 911-930, doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00006.1.

Menne, M. J., C. N. Williams, B.E. Gleason, J. J Rennie, and J. H. Lawrimore, 2018: The Global Historical Climatology Network Monthly Temperature Dataset, Version 4. J. Climate, in press. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-18-0094.1.

Peterson, T.C. and R.S. Vose, 1997: An Overview of the Global Historical Climatology Network Database. Bull. Amer. Meteorol. Soc., 78, 2837-2849.

Vose, R., B. Huang, X. Yin, D. Arndt, D. R. Easterling, J. H. Lawrimore, M. J. Menne, A. Sanchez-Lugo, and H. M. Zhang, 2021. Implementing Full Spatial Coverage in NOAA’s Global Temperature Analysis. Geophysical Research Letters 48(10), e2020GL090873; doi:10.1029/2020gl090873.

Source link : https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/monthly-report/global

Author :

Publish date : 2024-05-26 03:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.