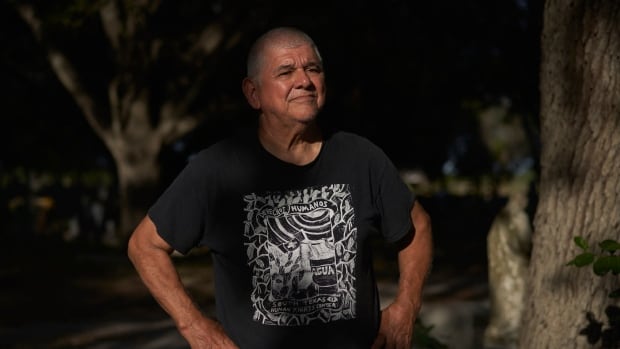

As It Happens6:34Eddie Canales, who set up nearly 200 water stations along the U.S.-Mexico border, dies at 76

Eduardo (Eddie) Canales was fuelled by both love and anger, says his friend and colleague.

Canales, a longtime union activist and migrant rights advocate, died on July 30 of pancreatic cancer. He was 76.

After decades of work in the labour movement, he founded the South Texas Human Rights Center in 2013, a non-profit that aims to prevent migrant deaths.

He spent much of the last decade of his life travelling along the U.S. southern border to place and refill large barrels of water for those making the dangerous — and often deadly — journey across the arid desert to the U.S.

“He couldn’t sit back and just watch people dying from thirst,” Nancy Vera, vice-president South Texas Human Rights Center, told As It Happens guest host Catherine Cullen.

“He’s left a tremendous void in my heart, and in the hearts of many people here in south Texas.”

Vera says Canales did this work because “his heart was full of love for other people.”

But he was also, she says, channelling his anger at a system that allowed countless people to die alone in the desert, their bodies often eaten by animals or dumped unidentified into mass graves.

“The immigration system has failed,” he said in a 2022 interview with the Guardian about the hundreds of migrants who die annually crossing into Texas. “The solution is to offer an ordered asylum pathway. You could fix this tomorrow.”

From labour to the border

According to an obituary in the Washington Post, Canales spent most of his career in the labour movement before turning his attention to the border after he retired to care for his ailing mother.

He organized for the United Farm Workers, the Service Employees International Union and the Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America, among others.

“It’s fulfilling enough to get people to be able to empower themselves and feel that they are taking steps to change their conditions,” he said in 2015 for an oral-history project at Texas Christian University.

Switching from union work to migrant advocacy was not much of a stretch, he told the New York Times in 2019. Both fields, he said, are about “developing a connection.”

Every week for the last decade or so, Canales filled up blue water drums that he’d spread throughout valley ranchlands and brush along the U.S. southern border. (Gregory Bull/The Associated Press)

Vera, a former teacher, says she first met Canales through his work with Corpus Christi American Federation of Teachers.

They were driving to the Rio Grande Valley one day on union business when, she says, Canales started telling her about the crisis of deaths at the border.

“It was all brand new to me. I had no inkling,” she said.

But it was something that would become all too familiar when she joined forces with Canales to fight for migrant rights.

“We would see the corpses,” she said. “A lot of people say these are men. They weren’t men. Some of them were boys — 12, 13, 14 years old.”

Vera says she’s seen horrors she’ll never forget, and which have created a “cold anger” inside her — the kind of anger that makes her ask: “Who’s to blame? And how are we going to make this right?”

“Eddie had those ideas,” she said. “He couldn’t stop.”

Bringing water to the desert

Canales fought alongside other activists to ensure that human remains found in the desert be DNA tested so their loved ones would know what happened to them. He also pushed for mass migrant graves to be exhumed so remains could be properly identified.

But he was perhaps best known as the man who brings water to the desert, work that was highlighted in the 2021 documentary Missing in Brooks County.

Canales would travel the border to place and refill dozens of 55-gallon blue barrels labelled “agua” — Spanish for water — in big block letters. On the lids, he’d scrawl contact information for the South Texas Human Rights Center.

The South Texas Human Rights Center estimates he placed nearly 200 of these water stations across seven counties, with many on private land owned by ranchers.

Canales, therefore, had to forge alliances with landowners.

In media interviews over the years, he said some of the ranchers he approached were easy to work with because they, too, had grown exhausted by seeing death on their land.

But others, he said, were a harder sell.

“He was able to convince some of them by telling them, ‘Hey, you know, if we provide these water barrels, they won’t come knocking at your house to try to get food from you or water from you,'” Vera said.

“Some of them, he wasn’t able to convince.”

Canales was born on Jan. 12, 1948, in Corpus Christi, Texas, to farm labourers Ignacio Canales and Consuelo Vidaurri de Ramos, according to an obituary in the New York Times.

He leaves behind a son, Eddie Jr., and a daughter, Erika.

Vera says she grew close with Canales over the years. They often laughed together, she said, and sometimes cried together.

“When he was first diagnosed with cancer, he came to me and we hugged for a long time, and we cried and he said, ‘I’m gonna beat this.’ I said, ‘Yeah, you can beat this, Eddie,'” she said, her voice cracking.

“I can’t believe that he’s gone.”

The only way to move forward, she says, is to continue his work.

“It’s going to be difficult without him. He was the mover and shaker. He had the energy,” she said. “My hope is that we carry on and that it gets better.”

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66bbde5175a04ca9979e976c181c9757&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cbc.ca%2Fradio%2Fasithappens%2Feddie-canales-obituary-1.7293295&c=2713154152526430064&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-08-13 11:06:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.