Play the episode “The Vanishing of Melanie James” of the Dateline: Missing in America podcast below and click here to follow.

Read the transcript here:

It’s called the Four Corners region, the area where four southwestern states meet: Utah, Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico.

There’s even a spot where you can stand in all four states at once.

Historically, that same spot also marks the land boundary of two American Indian nations: the Navajo Nation and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Reservation.

It’s a rocky landscape rich with Indigenous culture and history.

Some Pueblo ruins date back as far as 1300 A.D.

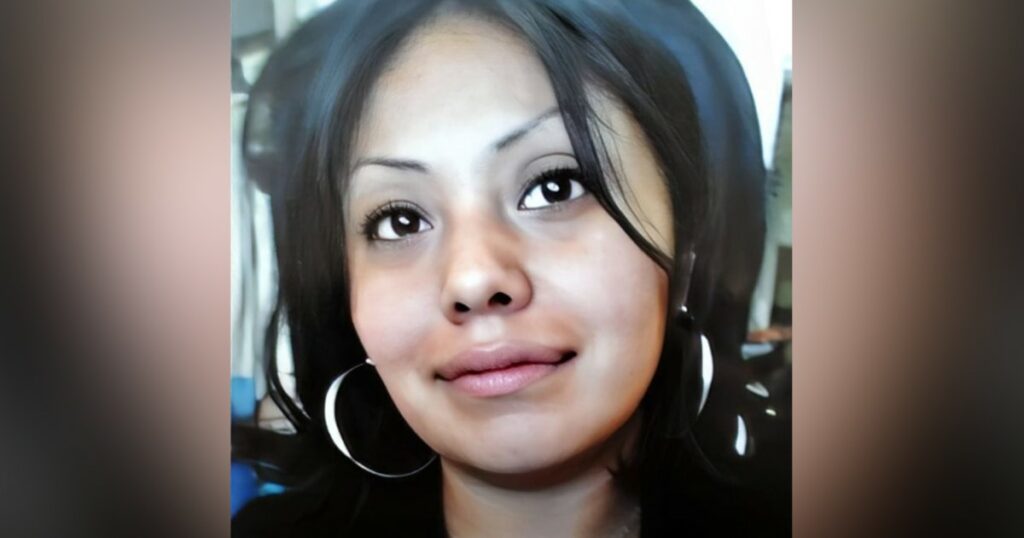

It’s in this area, in the town of Farmington, New Mexico, where a 21-year-old Native American woman went missing.

Her name is Melanie James.

This is her mother.

Lela Mailman: “I’m not gonna give up on trying to look for her. Every little opportunity I have to put awareness out there, is what I’m gonna do.”

Lela Mailman has been looking for her daughter for more than 10 years.

Lela Mailman holding a poster for her daughter, MelanieLela Mailman

Unfortunately, where she lives is a place where people like her daughter go missing much too frequently.

Melanie’s disappearance has baffled the community there and become part of a rallying cry in a persistent crisis.

Attorney Darlene Gomez: “We just have had this ongoing system of failures when it comes to Native Americans.”

Lela Mailman: “It’s been going on for centuries and centuries. But isn’t it time to stop it?”

Melanie’s family believes she is still alive, and still out there somewhere.

And they desperately want her back with them.

That’s where you come in.

Please listen closely, because you or someone you know might have information that could help solve this case and bring Melanie home.

I’m Josh Mankiewicz, and this is Dateline: Missing in America.

This episode is The Vanishing of Melanie James.

Melanie James grew up in Farmington with her two brothers and her sister.

Melanie is part Walker River Paiute, part Comanche.

Her mom says Melanie enjoyed Native American music growing up, especially when that involved dancing.

Lela Mailman: “She was funny. Loved to dance. Her and Melissa loved to dance together, to make routines. I’d come home from work, ‘Look, Mom! I made this up.’ And they would start dancing and show me.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “When I said, ‘Tell me about her, Lela,’ you smiled.”

Lela Mailman: “Just a lot of memories going through my mind. I could see her face right now, ‘Come on, kid. You got this.’”

Melissa James: “She was always making us laugh. Very caring person.”

That’s Melanie’s sister, Melissa James.

She says Melanie grew up deeply loved by her family. Then, as she reached her teen years, Melanie starting spending time with new friends. And it made her sister worry.

Melissa James: “She was hanging out with people that weren’t really good for her. People that would just get her intosubstances and, you know, drinking.”

That would eventually lead to some serious trouble with law enforcement.

At 18, Melanie took part in a burglary, and was arrested.

Lela Mailman: “She was small. So the people put her in through the window because she was small enough to fit. And then once they saw the cops, they all took off.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “They were trying to what, burglarize somebody else’s house?”

Lela Mailman: “Yeah, they were trying to get some, uh, jewelry and some other stuff so they could sell it.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “It definitely sounds like Melanie was running with the wrong crowd.”

Lela Mailman: “Yes.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “And I’m also thinking that both of you, at different times, said to her, ‘This is a bad idea. You’re hanging out with the wrong people.’”

Lela Mailman: “Yes, we did.”

Melanie pleaded guilty to the burglary, served some jail time, and was released in November 2013.

Her family says when they would confront her about her behavior, Melanie’s typical teenage response was cued up and ready.

Melissa James: “‘I know what I’m doing. I know what I’m doing.’”

Lela Mailman: “‘I got this.’”

Melissa James: “Yep. ‘I got this. I know what I’m doing and don’t worry about me.’”

Lela Mailman: “Yeah. And then that’s what a lot of our — our arguments were about because I didn’t like her friends — her so-called friends. Um, you know, ‘They’re only gonna get you in trouble.’”

By April 2014, Melanie’s family believed she’d put that group of friends behind her.

Lela Mailman: “She wanted to change her life. Um, she wanted to upgrade her life and stop doing the stuff that she was doing.”

Melissa James: “She knew that life wasn’t for her anymore.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “Sort of time to grow up.”

Melissa James: “Yeah.”

Melanie was about to turn 22 and, for her, growing up meant getting a degree.

Lela Mailman: “She was going up to the college to enroll in some classes. And then coming back from the college, she was gonna put job applications in.”

Her school of choice? San Juan College in Farmington.

Josh Mankiewicz: “What do you think she would’ve been studying?”

Lela Mailman: “Animals.”

Melissa James: “Yeah.”

Lela Mailman: “Veterinarian. She loved animals. That’s where she was going.”

It seemed Melanie was on that new path.

At least, that’s what Melissa thought up until the last time she saw her sister, on April 20th, 2014.

Melissa James: “I seen her on the way back from dropping off my son and I stopped at this church. And I — I seen her walking and I yelled at her. I said, ‘Mel, Mel.’ And she realized that it was me. So I pulled over, pulled into the church. It’s like a big old, empty parking lot.”

Melissa says she knew most of her sister’s friends.

But when she saw her in that parking lot, Melanie was walking alongside a young man Melissa had never met.

Melissa James: “This was one that I did not recognize.”

She says he was a slender African American man, about 6’ tall with short hair and a beard. He was wearing a navy-blue muscle shirt, with faded black pants and black and white sneakers.

Josh Mankiewicz: “Did Melanie tell you his name? Did she introduce you?”

Melissa James: “No, she did not. She just said that it was her friend and he kind of just stood quiet by the — by the driver’s side.”

Melanie told Melissa her new plan: She was headed to Albuquerque, three hours away.

Melissa James: “She was just telling me about how she wanted to go to Albuquerque because she just felt like she was — she didn’t really want to be here.”

When Melissa did not hear anything from Melanie, she began to worry.

Lela was not hearing from her either.

Lela Mailman: “I just wanted her back home, wanted to know where she was and how she was doing. And she just didn’t call me at all or have any contact with me at all.”

Lela says eventually her anxiety became too great, and she started searching for Melanie herself.

Lela Mailman: “I was out there looking for her, driving around two, three o’clock in the morning.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “This cost you a job at one point, didn’t it?”

Lela Mailman: “Yes, it did.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “Because you were spending all your time looking for Melanie.”

Lela Mailman: “Yes. It cost me a job, but that didn’t matter. That was just a job, OK? I can always get another job, but my daughter cannot be replaced. And that was the only thing going through my head at the time. I have to find her. There’s no doubt about it, I have to do what I gotta do.”

With no sign of Melanie, Lela decided she needed to report her daughter’s disappearance to Farmington police.

In that missing persons report an officer noted that Lela Mailman told him, “Melanie has had trouble with alcohol, been in trouble and arrested in the past, as well as been gone for days at a time, but has never been gone this long.”

The timing of that report is one thing Lela and the department do not agree on.

Farmington Police Chief Steve Hebbe notes the family made that first report in June of 2014, two months after Melanie vanished.

Lela says it was much sooner.

Whatever actually happened, police say it was a two-month delay, which became an instant roadblock for them.

Chief Hebbe: “The reporting, from the beginning, is — is just a little harder for us. We’re scrambling a little bit because nobody’s seen her for a little while.”

Or did they? A snippet of video was about to jolt this family with some sudden, unexpected hope.

Lela Mailman: “Sandra showed me the footage and I ID’d her.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “No question that’s Melanie?”

Lela Mailman: “No question. Yes, it was Melanie.”

Lela Mailman had been doing everything she could to find her daughter, all the time afraid she might never see her again.

Then it came, in September 2014, five months after Melanie disappeared — a new reason for hope.

A former co-worker of Lela’s named Sandra said she had spotted Melanie at a Family Dollar store in Farmington.

Lela Mailman: “I worked with Sandra. I worked with her at Goodwill. And so she knew Melanie.”

Lela was at work when she got the call from Sandra, so she sent one of her sons to go check it out.

Could Melanie really be alive and well?

Unfortunately, by the time her son arrived at the store, Melanie was gone.

Lela says she later asked to see the security footage of that day, and the store manager agreed.

Josh Mankiewicz: “And — no question — that’s her?”

Lela Mailman: “Yes, definitely was her.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “How’d she look?”

Lela Mailman: “Well, she looked healthy. She didn’t look skinny or like somebody that was on the street, you know, doing drugs and everything. She was pretty well-kept.”

For Lela, those few seconds of security video were equal parts encouraging and ominous.

Her missing daughter was alive and, apparently, healthy.

At the same time, Lela says the camera shows Melanie buying a single lollipop and looking around as if someone might be watching her.

Lela Mailman: “She liked lollipops. But the nervousness or the way she carried herself that day was definitely not her.”

Melanie’s sister Melissa has her own theory about what’s happening in that video.

Melissa James: “She would only buy one item like that if she was nervous. There was a few times where, um, some creepy people would just, like, try to follow us or whatever. So we would go inside of the nearest convenience store and we would just buy, like, one item — one thing. So, to me, that was my signal as some — somebody was definitely following her, because that is something that me and her used to do, too. ‘OK, we’ll just go in here. We’ll buy something.’ Because that’s what our mom taught us to do.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “But the cashier didn’t say anything. The cashier never called police.”

Lela Mailman: “No.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “So if — if your friend hadn’t been there, you wouldn’t know about that.”

Lela Mailman: “Yeah. I wouldn’t have known at all.”

That video would have been a great piece of evidence, except for one thing…

Farmington police have never seen it. They say that by the time they found out about it, the video had been erased.

Detectives interviewed Sandra and confirmed her account of seeing Melanie at the dollar store, but without video it remains a tantalizing footnote.

Still, as Melissa thought about that nervousness her mother said Melanie displayed in the video, she thought about someone, a man the family told police Melanie was afraid of: Her ex-boyfriend.

Josh Mankiewicz: “She’d been in a relationship with a guy who has been described as abusive. Were — were you aware of that?”

Melissa James: “At first, we didn’t think it was abusive physically. It was more like he was controlling.”

Melanie’s family says that boyfriend’s controlling behavior later took a turn for the uncontrollable.

Melissa James: “I know there was a few times where he did get physically aggressive and grabbed her and maybe, like,tossed her around the room.”

Lela Mailman: “She called me up one day and she said, ‘Mom, come get me in Aztec.’”

Lela immediately made the half-hour drive from Farmington to Aztec, New Mexico to pick up her daughter.

Lela Mailman: “She was, you know, kind of sobbing pretty hard. And I kept asking her what’s wrong. And she goes, ‘I’m just happy to see you.’ You know, she was hiding the whole thing. And he was standing right there. And I said, ‘What happened to your ears?’ because it was cut from her earring. She goes, ‘Mom, I just wanna go home.’ So I said, ‘Alright.’ So we went across to get — get the stuff. I had a weird feeling. I said, ‘You’re not going in there yourself.’ So I got the bat and I got the Mace and we went in. We got her stuff. And as we were going back, she just broke down crying. And she goes, ‘Mom, he — he threw me over on the floor and he started hitting me with his fist.’”

After they left, Melanie told her mom she couldn’t take it anymore and called police.

On March 17, 2014, her ex was charged with false imprisonment and aggravated assault against a household member.

Josh Mankiewicz: “She filed charges on him and he went to jail.”

Lela Mailman: “Yeah. He went to jail, but he continued to try to write, you know, letters to her.”

It wasn’t long before the clues and theories in Melanie’s case dried up like a creek bed in this corner of New Mexico.

Months turned to years, as her case shuttled through a series of detectives… Still with no answers.

Through it all, Lela grew more and more frustrated, believing that police were not giving her daughter’s case adequate attention.

Lela Mailman: “It seems to me, the only time that we would get any response, uh, before, was I had to constantly call. I had — I had to keep bugging them, bugging them, bugging them before I could get a, like, an answer.”

She says recently that began to change.

In January 2024, Chief Hebbe assigned Farmington Police Detective Daven Badoni to put some fresh eyes on the case.

Detective Daven Badoni: “I just need tips or people to come forward and give us statements.”

Since then, Badoni has been re-investigating, looking for clues that were missed.

He quickly learned police did have some key evidence early on.

Detective Badoni: “This is four days after the last time Melissa saw Melanie.”

On April 24th, 2014, officers found a black duffel bag and a woman’s purse, both belonging to Melanie James.

Those were partially hidden in an alleyway behind a strip of businesses on 20th street, not far from Farmington’s public library and a movie theater.

Detective Badoni: “The officer found the bag and found two cell phones in there, called the last number that was — was called on there. And that — that was a guy named Brian. So, Brian said Melanie had left his place the night prior.”

Brian was a friend Melanie spent time with.

At that point police were not searching for Melanie as a missing person.

So officers took a “found property” report and put Melanie’s belongings in evidence for safekeeping.

As he re-investigated in May of 2024, Detective Badoni was able to track down Brian and ask about the last time he saw Melanie.

Brian said he remembered Melanie was hanging out with him that night.

Detective Badoni: “He was staying with family at a — at a residence on 21st street here in Farmington, uh, which is a few blocks away from where her bags are found. So, Brian recalled that Melanie was intoxicated, and she was knocking on doors — on neighbors’ doors — and police were called.”

Brian says he told Melanie she was disturbing the neighbors and had to get out of the house. And she did.

Detective Badoni: “Melanie grabbed her bags and left. So that was the same day, April 24th, about one o’clock in the morning.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “Did police encounter her on that day?”

Detective Badoni: “No. No. So, police ran two names. One of them was Brian and then another male, but no. They did not run Melanie. I believe she was gone before police officers arrived.”

Police think Melanie may have walked a few blocks to that spot in the alley where they later found her purse and duffel.

They also learned Melanie had been couch surfing, staying with various friends here and there around Farmington.

That meant she would sometimes stash her belongings in a safe place.

Detective Badoni: “It was common for her to hide her bags in a — in a nice area of town and then maybe come back for it later.”

The detective says Brian’s story about Melanie has remained consistent, but he notes Brian did reveal one new detail in an interview earlier this year.

Detective Badoni: “The only thing that Brian added was that a week later he received the phone call from, uh, Melanie and that she was in Albuquerque, and was asking him for money to return back to Farmington.”

That new bit of information matches what Melanie told her sister: That she was headed to stay in Albuquerque for a while. It sounded as if she got there.

Josh Mankiewicz: “So now the timeline’s extended a little bit. You believe Brian — that she was alive as of four days after her family saw her. And, uh, sounds as if she’s not with anybody else and she’s not under duress.”

Detective Badoni: “That is the perception given to us at this time, yeah. It sounds like she was in Albuquerque a week after April 24th. So that put us in May, uh, of 2014.”

Why would Melanie be headed to Albuquerque?

Was she running away from something? Or someone?

Melissa couldn’t shake the thought that her sister had to be in danger.

And her mind kept drifting back to Melanie’s ex.

Melissa James: “I knew she was scared of him. She just wanted to, you know, get away from him.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “Where was that guy when Melanie disappeared?”

Melissa James: “So, she had heard at the time that, um, he was out of jail.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “So Melanie at least thought, ‘He’s looking for me.’”

Melissa James: “Mm-hmm.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “And ‘I have to hide.’”

Melissa James: “Yeah.”

Having a missing loved one doesn’t come with a manual.

There is no one-size-fits-all answer for how to cope with a disappearance.

Melanie’s kin have now lived a decade without her.

Josh Mankiewicz: “What’s this done to your family?”

Melissa James: “It has torn us apart. Completely destroyed us. There’s times where we don’t have contact with each other because we’re so depressed and we don’t — we don’t want to show each other because we — we are trying to be strong for each other.”

They’ve also come to realize they are far from alone in their quest for answers.

New Mexico has one of the highest rates of missing and murdered Indigenous women in the nation.

And according to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, four out of five Indigenous women have experienced violence during their lifetime.

Facing those statistics, Lela decided there was only one response, and that was to fight.

Lela at an event: “And to this day, I am still looking for my daughter.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “When you’re talking about her story to — to whoever, when you’re protesting, when you’re marching, when you’re trying to get the word out, that actually helps you as well as maybe her.”

Lela Mailman: “It helps us let go of some of the emotions that we have at the time and also to give us the strength that we need to carry on.”

Lela relied on that strength at an event in 2022. Deb Haaland was giving a lecture at the University of New Mexico and opened the floor for questions.

Josh Mankiewicz: “I was watching some video of you talking to Deb Haaland at that meeting, the interior secretary.”

Lela Mailman: “Yeah. Mm-hmm.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “And, um, what I thought was that you were doing a very good job of concealing how angry you were.”

Lela Mailman: “Yeah.”

Secretary Haaland is in a unique position.

In 2021, she became the first Native American to serve as a U.S. cabinet secretary.

She’s also become a target of criticism for how little has changed over many decades.

Lela Mailman: “With the first two families that went up, she kept saying, ‘I sympathize with you.’ And that’s when I said what I said on the tape.”

Deb Haaland at event: “Ma’am I’m so sorry for your loss. I truly am.”

Lela Mailman at event: “I don’t need sympathy. I need understanding. We just need help. I think this has gone on long enough and is getting worse… I just wonder, what else are you going to do for these Native Americans that are missing?”

Deb Haaland at event: “I want you to know that we’re trying. We’re working as hard as we can.”

We contacted Secretary Haaland’s office for further comment.

They noted that one of Haaland’s first acts as secretary was to establish the Missing and Murdered Unit, which works to expand collaborative efforts with other agencies when it comes to missing and murdered Indigenous people.

Her team told Dateline Haaland is determined to make this issue a top administration priority.

Attorney Darlene Gomez says she’s also making it a top priority.

Josh Mankiewicz: “Just for listeners who maybe don’t follow this as much, the hashtag that you see online, uh, MMIW — Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women — uh, that came into being this century — after 2000, uh, but that problem’s a lot older, isn’t it?”

Darlene Gomez: “Correct. So, if you look back at the time of Christopher Columbus, and the slave trade, and the conquistadors that came into New Mexico, and then we have the federal government that made tribes go on to reservations. We have boarding schools. We have the water being taken away from them. We have poverty. We have alcohol introduced to the Native Americans. And we just have had this ongoing system of failures when it comes to Native Americans.”

On their website, the Bureau of Indian Affairs notes that many MMIW cases remain unsolved due to a lack of investigative resources.

Josh Mankiewicz: “People have gone missing and there’s been no accountability and no one to investigate it?”

Darlene Gomez: “Correct.”

A New Mexico native, Darlene met Lela at a rally and took up Melanie’s case. She helped Lela get a billboard put up to find her daughter.

Melanie’s is one of many MMIW cases Darlene has taken on pro bono.

She helps families plan events and marches, speaks to the media to raise awareness, and sits in as an advocate in meetings with police.

She says Melanie’s disappearance mirrors similar MMIW cases across the country.

Josh Mankiewicz: “She was 21 years old, so she was technically an adult. Police rarely respond to a missing 21-year-old the way they do to a missing 10-year-old, for example. Uh, she had a previous criminal record, which sort of changes the way that law enforcement reacts to someone when they’re missing, because that can sometimes lead to an assumption that, ‘Well, they’ve done something to put themselves in harm’s way. We’re not gonna go look for them.’”

Darlene Gomez: “Correct. And I think one of the things that you talked about was victim blaming. So, we see a lot of this. And even in this report, talking about, um, not having a job, having criminal charges. She had been in a domestic violence relationship prior to her going missing. I think cases like these, they just get put on a shelf. I don’t know if there was policies and procedures in place to ensure that these cases get investigated.”

I asked Farmington Police Chief Steve Hebbe about that.

Josh Mankiewicz: “You know, this is something that comes up in missing cases all the time. When they have a criminal record, do you look for them differently? Is that a lower standard? Is there a — sort of an assumption by law enforcement that, ‘Well, they’ve probably done something to put themselves in harm’s way.’”

Chief Hebbe: “No. In this case, it — it just makes it a little harder — the lifestyle of, uh, she doesn’t really live in — in a place and have a nine to five job. It’s just — it’s just a little more complex for us to do it, but it certainly doesn’t — it doesn’t affect our response. It just affects our ability to — to achieve the same results.”

The Chief points out the challenges his department has faced.

Remember Melanie’s purse found in that alleyway?

Well, Farmington police did submit samples from it for DNA testing. That was much later…

Here’s Detective Badoni.

Detective Badoni: “We requested that the swabs be tested through our state laboratory, which is the New Mexico Department of Forensic, uh, Laboratory, it’s in Santa Fe. And — and it’s our state lab where we send all evidence. Um, so they declined to pro — to process it because we did not have evidence of a crime, um, and that’s something that they require. They require a criminal offense, uh, to process any DNA. So that’s kind of where we — we ran into an issue.”

It’s sort of a law enforcement Catch-22.

No proof of a crime means no DNA testing.

Detective Badoni: “There was nothing obvious to those bags that something had happened to whoever was carrying those bags.”

Chief Hebbe: “At this point we don’t have — we don’t have any clue whether, uh, there’s a crime or there isn’t.”

Even so, the department didn’t submit that purse for testing until two years ago. That’s eight years after Melanie had disappeared.

Josh Mankiewicz: “Chief, are you confident that your department has done all it could from the beginning?”

Chief Hebbe: “I haven’t come across information that shows me, look, we — we dropped the ball here or here. And I’ll be honest with you and tell you, you know, I — I’ve certainly, in my time as chief, we’ve had those days, uh, where we didn’t do a good job. And, you know, you — you’re gonna own those and you’re gonna try and figure out, um, what we didn’t do right.”

Farmington is running into the same problems faced by a lot of departments.

Resources are limited and searching for the missing is never the top priority.

Josh Mankiewicz: “Uh, chief, how many sworn officers on your force?”

Chief Hebbe: “Deployed, we’re — we’re around 105.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “In a city of how many people?”

Chief Hebbe: “45,000.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “And the only guy on missing persons is the one next to you.”

Chief Hebbe: “Correct.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “So it’s a tall order.”

Chief Hebbe: “It’s a tall order.”

Chief Hebbe says he’s determined to get answers in Melanie’s case.

Chief Hebbe: “I mean, to this day, you know, I — I think it’s terrible. Uh, and I would not want to be in that position of — of having a family member that’s gone for 10 years and the emotions that go around that. We still are looking. We actually do care about this. And, uh, we’re gonna do all we can to see if we can bring this to conclusion. We need leads. We need other people to help us try and locate her.”

Detective Badoni says he’s actively chasing any new lead he can find.

Detective Badoni: “I’m letting my evidence lead me where I need to go, but I’ll talk to whoever — anybody. This whole case revolves around people that know her or came across her. And — and at that point I would hope that they would give me information.”

People like that ex-boyfriend.

The detective did look into his whereabouts at the time Melanie disappeared.

Detective Badoni: “We could confirm that through our jail records he was incarcerated at the time in April and even I believe, and — and most of the time in May he was incarcerated.”

Josh Mankiewicz: “So there’s very little chance that he’s involved in her disappearance.”

Detective Badoni: “Yes.”

Melanie’s ex pleaded guilty to aggravated assault in September 2014, five months after her disappearance.

Prosecutors dropped that other charge of false imprisonment.

However, the detective has yet to interview him.

And he says he can’t rule out any potential suspects until he talks with them.

He’s also hoping to track down that friend Melissa saw Melanie with in that parking lot, days before she went missing. She says he was a slender African-American man, about 6’ tall with short hair and a beard.

Detective Badoni: “I need this unknown Black male to come forward and give me a statement. That way I can check his name off the list, and then we can move on and — and not focus on — on him.”

Melanie’s family says they are pleased with the way Badoni has handled the case so far, after years of feeling abandoned by law enforcement.

Lela Mailman: “The detective that’s working on the case has really gave us a lot more information than the other detectives have before. And it gives us a lot more hope, you know, that he’s really doing something.”

Melanie’s mom, Lela, does not just hope her daughter is alive.

Lela Mailman: “I do think she’s still — well, I know she’s still alive. You know, like — like a connection. I loved her before she was born and I loved her more after she was born. So, in my spirit, I think she’s — I know she’s alive. I just know she’s alive in my heart. I won’t give up on her. I won’t give up on you, Mel, wherever you are. I love you.”

Melissa is still clinging to that last moment she saw her sister.

Melissa James: “Deep down, I know she’s alive and I have to hold on to that hope, but I am human and I struggle with it every day. It just doesn’t make sense. Throughout 10 years there’s no way that she — there’s no way she would not call me. There’s no way she would not stop by my house.”

And Melissa has her own theories of where her sister might be.

Melissa James: “I think she’s either being held hostage or she’s hiding. I know she knows how to survive out there. She’s really smart. She knows which way to take, how to survive without a phone, without ID, without a lot of things. She knows how to take care of herself.”

Lela has vowed that she will continue to advocate for missing and murdered Indigenous people long after Melanie’s case is solved.

Lela Mailman: “I told everybody that I’m not gonna stop when Melanie’s found. Because I know what it feels like and what every family is going through right now because of their loved one is in the same situation as Melanie.”

In March of 2024, the New Mexico Department of Justice set up a new website to serve as a hub for information, advocacy, and support — all related to cases of missing Indigenous people. There is also a database for reporting and searching for missing Indigenous persons.

Melanie James is listed there.

Here’s where you can help:

Melanie James would be 32 years old today.

She’s 5’ tall and weighed about 115 lbs. at the time of her disappearance.

Her hair was dark black and one of her top front teeth was chipped. Melanie has a tattoo of a spade on her right hand.

Anyone with information about Melanie’s disappearance should call the Farmington Police Department at 505-334-6622 or the Detective Tip Line at 505-599-1068.

To learn more about other people we’ve covered in our “Missing in America” series, go to DatelineMissingInAmerica.com. There you’ll be able to submit cases you think we should cover in the future.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66b434d5c1524244b4741d73a451bb39&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.nbcnews.com%2Fdateline%2Fdateline-missing-in-america-podcast%2Fdateline-missing-america-podcast-covers-april-2014-disappearance-melan-rcna164053&c=906850840617149962&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-07-30 08:38:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.