The issue has become a focus for several environmental organizations working in the region, as well as for the Paraguayan government. “Together with the National Forestry Institute, we ensure that any new livestock or agricultural development projects implemented conserve the native forest reserve areas that they must maintain and that they support our corridors,” says Carlos Monges, head of wildlife at Paraguay’s Ministry of the Environment and Sustainable Development.

Villalba explains how this works: “If one neighbor leaves their 25% [of forest] intact, we try to have the next-door neighbor match this, and if they have to reforest, we encourage them to do so in a way that’s consistent with the other neighbor’s reserve. In this way, we are managing to ensure that 30%, and even 40%, of forest cover remains in many properties.”

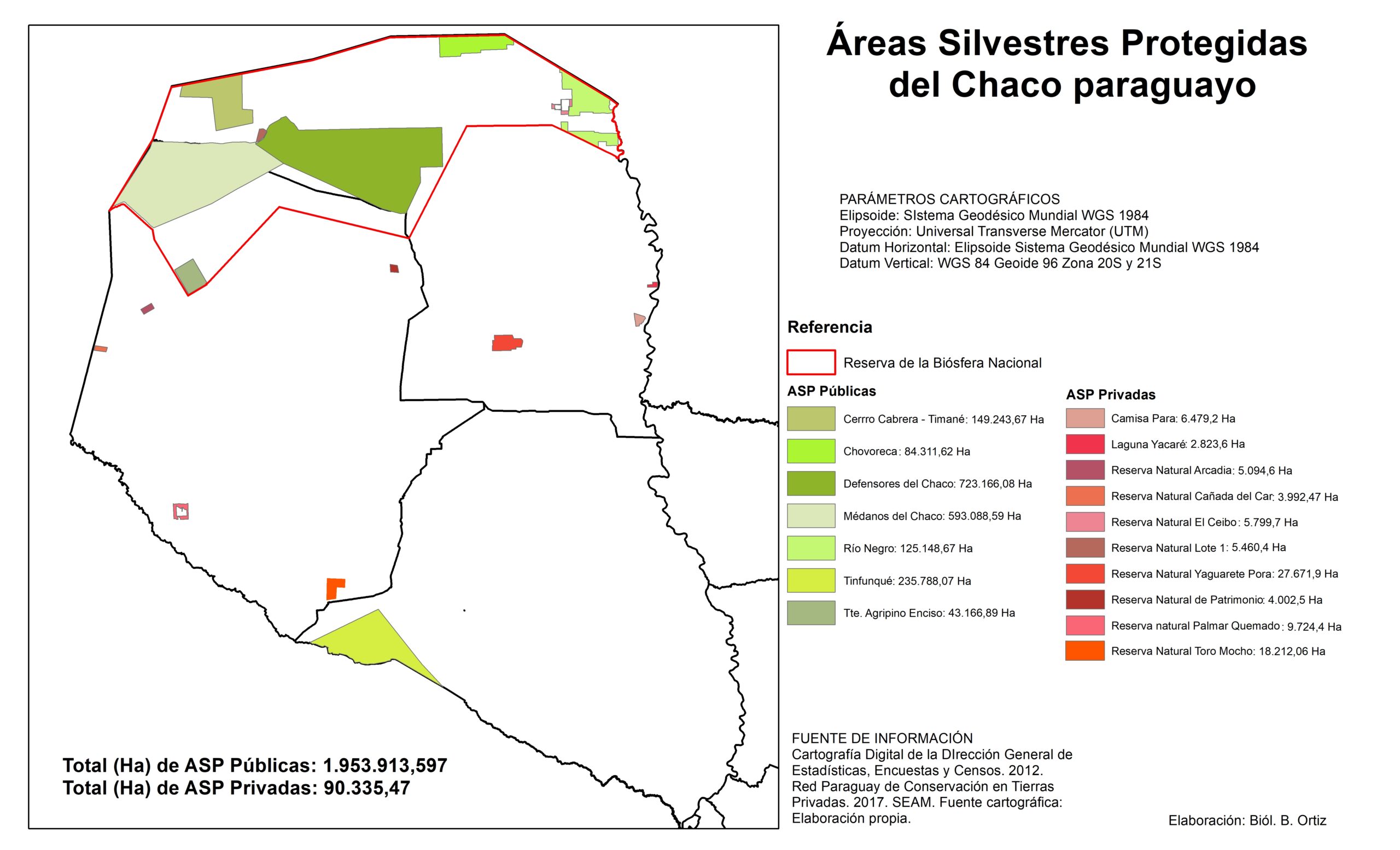

Defensores del Chaco National Park is the largest protected area in Paraguay: at 720,723 hectares, it’s 60 times the size of the country’s capital, Asunción. It’s bordered to the west by Médanos del Chaco National Park, and the proposed corridor to the northwest would link it with Cerro Cabrera-Timane Nature Reserve. That would then make it contiguous with Kaa-Iya National Park in Bolivia. The other corridor radiating out of Defensores del Chaco would link it with Chovoreca National Park to the northeast.

In this way, an extensive loop would be closed for all the native wildlife in the region; not just jaguars and pumas, but also anteaters (Myrmecophaga tridactyla), jaguarundis (Herpailurus yagouaroundi), southern tiger cats (Leopardus guttulus), tapirs (Tapirus terrestris), various species of armadillos, Chaco chachalacas (Ortalis canicollis), boas (Boa constrictor) and South American rattlesnakes (Crotalus durissus).

Map of protected areas in the Paraguayan Chaco. Defensores del Chaco National Park, in dark green, is the largest of these. Image courtesy of WCS Paraguay.

Map of protected areas in the Paraguayan Chaco. Defensores del Chaco National Park, in dark green, is the largest of these. Image courtesy of WCS Paraguay.

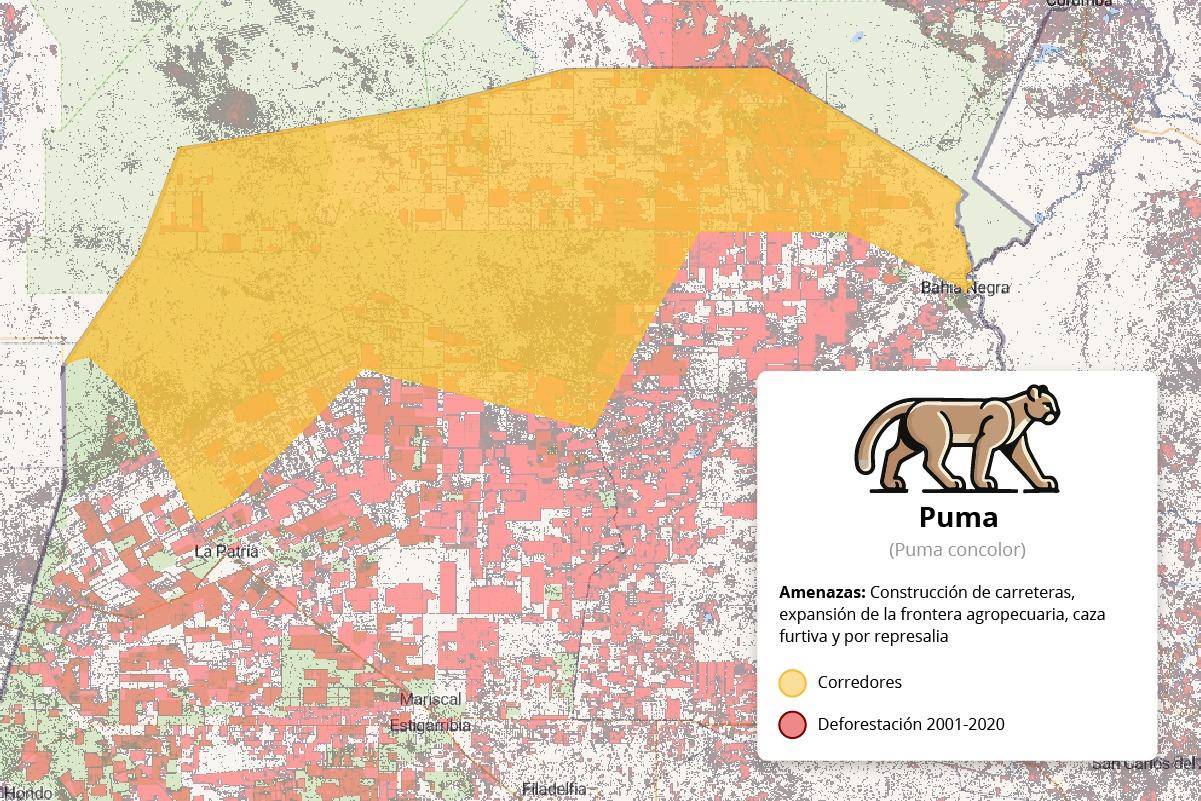

Connecting up protected areas in the Paraguayan Chaco provides an important corridor for pumas and other species to move around. Image by Eduardo Mota for Mongabay Latam.

Connecting up protected areas in the Paraguayan Chaco provides an important corridor for pumas and other species to move around. Image by Eduardo Mota for Mongabay Latam.

“Both corridors pass through farmland, mostly livestock farms, although soybean cultivation has also been introduced recently,” Villalba says. “However, in all cases, these fields are required to leave 25% of their forest intact, and this is strictly enforced.”

In fact, Law No. 422/73 establishes the exact areas to be conserved, which extends to 50% if a farm is located within the three sectors of the country that Paraguay has declared a Biosphere Area. Of these, the Chaco Biosphere Area is by far the largest, occupying 7.4 million hectares (18.3 million acres). The law even provides for the width of the forest windbreaks, groups of trees planted in a row to provide protection against wind and wind erosion. These windbreaks can be seen in agricultural areas, pastures and other areas devoid of vegetation.

“We, from the ministry, carry out audits in these companies every two years to ensure compliance with the General Environmental Plan that each one must present to authorize its operation, and the fines for deforesting more than what’s permitted range from 20,000 to 40,000 days’ wages,” Monges says. “If we consider that currently each day’s wage is equivalent to 110,000 guaranĂes [$14], we see that it’s not cheap to break the regulation.”

The legal obligation to preserve 25% of forest on a farm results in patches of native forest amid deforested plots. Image courtesy of Andrea Ferreira.

The legal obligation to preserve 25% of forest on a farm results in patches of native forest amid deforested plots. Image courtesy of Andrea Ferreira.

Pumas and jaguars are, without a doubt, the kings of the Chaco ecosystem, characterized as a tropical dry forest. Their very different characteristics can be seen in their adaptability, which is always more noticeable in pumas. Puma can adapt quickly to habitat changes, often approaching and even crossing through urban areas. They also have a higher reproduction rate, are usually less cautious than jaguars, yet can still camouflage themselves in the forest, providing some protection against being shot. All this explains their wide distribution in Paraguay, although no specific studies give a definitive number for their population.

“Any project that aims to census a puma population over a large territory is very expensive and complex to undertake,” says MarĂa JosĂ© Bolgeri, a biologist with WCS in Argentina. “That’s why it is so difficult to obtain data on their density or abundance.”

Anything that improves connectivity between protected areas benefits both species, but in the specific case of the puma “it will result in a greater availability of prey without losing the cover provided by the forest and without [the puma] being exposed to [hunting] by farmers who feel that its presence threatens their herd of goats, sheep or calves,” Villalba says.

This is an important point, she notes: “The greatest number of complaints is always in relation to puma activity.”

Towards the north, in the area of Chovoreca National Park, the vegetation ceases to be purely Chaco dry forest and starts transitioning into the lusher savanna landscapes of the Bolivian Chiquitania and Brazilian Cerrado. Image courtesy of Andrea Ferreira.

Towards the north, in the area of Chovoreca National Park, the vegetation ceases to be purely Chaco dry forest and starts transitioning into the lusher savanna landscapes of the Bolivian Chiquitania and Brazilian Cerrado. Image courtesy of Andrea Ferreira.

Ongoing conflicts between pumas and ranchers

Habitat fragmentation, hunting, and especially conflicts with ranchers are the main challenges that pumas face in the area. Hugo González is the general veterinarian at Estancia Madrejón, a 37,000-hectare (91,000-acre) ranch located in the corridor that connects Chovoreca and Defensores del Chaco parks. It’s home to some 7,000-8,000 head of cattle, down from 14,000 a few years ago. “The drought forced us to get rid of many cows. We’ve had very little rain for three years; we completely depend on it here because the groundwater is too salty,” González says.

Big cats preying on calves has always been a problem for local ranchers, whose most common response is to hunt down and kill the animals. “Rural people naturally like hunting, there’s no denying that, but the general policy is that we have to live with that,” González says. “We’re close to Defensores del Chaco National Park and we don’t want to kill any animal, so we’ve been working with WCS for over a year. They’re providing us with alternative methods to reduce puma and jaguar attacks,” he adds.

“A puma in heat, or one that’s teaching its cubs to hunt, can kill four or five calves in one night,” Villalba says. This behavioral characteristic, combined with a larger population, would explain the higher puma mortality rate recorded in the region.

A calf killed by a puma on a cattle ranch near Chovoreca National Park. Some large ranches expect to lose up to 300 animals per year to attacks by wild predators. Image courtesy of Marianella Velilla.

A calf killed by a puma on a cattle ranch near Chovoreca National Park. Some large ranches expect to lose up to 300 animals per year to attacks by wild predators. Image courtesy of Marianella Velilla.

WCS collaborates with a dozen large ranches to ensure that their meat gets a “sustainable” certification, thus increasing their export potential while also reducing the rate of conflict with big cats. “A cultivated field without a windbreak is more challenging for a large feline because it interrupts the corridor, but another field with livestock, a well-preserved corridor and sufficient water attracts potential prey for felines, increasing encounters with livestock, and the amount of predation and conflict,” Villalba says. “In this case, interventions are necessary to reduce the impacts, using other animals (donkeys or buffalos), bells or LED lights to keep pumas away from calves.”

The collaboration of the cattle ranchers who occupy the corridor between Chovoreca and Defensores del Chaco is something that many of those involved in the issue highlight.

“There is a very strong desire to increase agricultural activity in the area, but the people who make up the Agua Dulce Agricultural Association [APAD] are very interested in sustainable development,” says Thompson from Guyra Paraguay, who’s also a researcher with the National Science and Technology Council of Paraguay. “In Guyra we’re working with them on projects related to connectivity for wildlife.”

Villalba and Monges agree that collaboration is key. According to APAD, the district of Agua Dulce is home to the largest expanse of forest in Paraguay, and maintains more than 75% of its forested area due to residents’ strong commitment to conservation.

This aerial view shows how a windbreak can help wildlife move around without having to cross a road or farmland. Image courtesy of Andrea Ferreira.

This aerial view shows how a windbreak can help wildlife move around without having to cross a road or farmland. Image courtesy of Andrea Ferreira.

The threat of asphalt

Thompson says the support of the ranchers, a boon to the long-term survival of pumas, is not without contradictions: “They’re producers and their priority is to produce. Which is why, for example, they want asphalt roads to reach the region,” he says.

“There will be even more people living in Agua Dulce, a town that’s already grown a lot in recent years, and that will endanger the area’s ecological integrity,” he adds. “It must be understood that, in general, the biggest problem for big cats is people.”

For now, the difficulty accessing the region plays in the pumas’ favor. “In terms of world classification criteria, Cerro Cabrera-Timane Natural Reserve, for example, is still a purely wild area, and despite the pressures it has been under in the last 10 or 15 years, the only isolated [Indigenous] communities outside the Amazon still persist there,” Thompson says.

A puma walks through a clearing in Defensores del Chaco National Park. Image courtesy of WCS Paraguay.

A puma walks through a clearing in Defensores del Chaco National Park. Image courtesy of WCS Paraguay.

However, the situation is about to change in other places. One of the roads set to be paved divides Defensores del Chaco National Park in two. “And there are other branches that will be paved in that area of Defensores,” says the environment ministry’s Monges, adding that this would greatly affect the wildlife. “That’s why we’re talking about establishing traffic controls at the entrances and exits, building overpasses for animals, limiting traffic speed with speed bumps, and applying heavy sanctions and fines for any infractions that may be committed,” he says.

Deforestation rates aren’t decreasing

In Chovoreca National Park, the agriculture sector is in fact gaining ground, even though the area’s extreme dryness may seem like a limiting factor for its expansion. Monges says new production systems and technologies, along with pastures that adapt to climate conditions, and the low economic yield that meat provides to many producers, is causing a slow migration of agriculture to these areas.

“If we take the entire Paraguayan Chaco as a whole, the reality is that the agricultural frontier is expanding and the general rate of deforestation remains high,” he says. “Every day more development projects are presented and several companies with licenses are now beginning to work their previously idle fields. In the immediate future, we will have to redouble control and protection activities.”

A puma captured by camera trap. Image courtesy of Guyra Paraguay/CCCI/Jeffrey J. Thompson/Marianela Velilla/Juan Campos Krauer.

A puma captured by camera trap. Image courtesy of Guyra Paraguay/CCCI/Jeffrey J. Thompson/Marianela Velilla/Juan Campos Krauer.

In Paraguay, very few species can be hunted for sport; most are birds, such as the Chaco chachalaca, or invasive species, such as the wild boar (Sus scrofa). That makes poaching a persistent problem.

“It’s quite common to find people with weapons walking along the side of the street or the roads that lead to national parks,” Monges says. He adds that poachers sometimes trick Indigenous communities into allowing them to enter forest areas to hunt in exchange for food. “It’s a very particular characteristic motivated by their nature and their worldview,” he says.

Indigenous Pykasu, Siracua and Ă‘u GuazĂş communities are dotted around the protected areas in this northwestern corner of the country, including near the biological corridor planned between Defensores del Chaco National Park and Cerro Cabrera-Timane Nature Reserve. Successful conservation will require educating the communities, experts say.

A pair of pumas captured by camera trap on the edge of a path. If they don’t sense any danger, pumas tend to be curious and unconcerned about their surroundings. Image courtesy of WCS Paraguay.

A pair of pumas captured by camera trap on the edge of a path. If they don’t sense any danger, pumas tend to be curious and unconcerned about their surroundings. Image courtesy of WCS Paraguay.

There are also calls for oil and gas prospecting in the region. “The time to plan and implement the corridors is now,” Thompson says. If not, says Monges, “Certain activities, such as road-paving projects in the area, could have a very strong impact on wildlife populations. Not only pumas and jaguars, but the entire chain that falls beneath them.”

For now, pumas continue to move around in the northern Paraguayan Chaco. But the approaching asphalt and advancing farmland threaten to present new challenges. These will put the cats’ opportunistic and resilient character to the test more than ever.

Â

Banner image of a puma (Puma concolor). Image by Kevin Nieto for Mongabay Latam.

This story was first published here in Spanish on Oct. 17, 2024.

![]()

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=672de9ef79234f12b1ba9d4e2a6af20b&url=https%3A%2F%2Fnews.mongabay.com%2F2024%2F11%2Fparaguays-pumas-adapt-with-some-help-to-a-ranch-filled-landscape%2F&c=6538052816228347869&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-11-07 21:06:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.