In 1541 the Mixtón War broke out in the kingdom of Nueva Galicia (western Mexico). When the local Chichimec people besieged the capital city of Guadalajara, one of its inhabitants, Beatriz Hernández, acted with determination. As chronicled by the Jesuit historian Mariano Cuevas, she addressed all the terrified women who were crying in the church, saying, “now is not the time for fainting,” before taking them to the safe house and locking them in. Hernández then put on light body armor and took up a short lance. Throughout the battle, she protected the entrance to the building and the women and children sheltering inside. The founding charter of Guadalajara contains the names of the 63 colonizers who survived the battle against the Chichimec; among them is Beatriz Hernández.

Another brave woman, Doña Mencía de los Nidos, stood firm in the defense of the city of Concepción, in southern Chile. And when, in 1554, Governor Francisco de Villagrá ordered the evacuation of the main square because of the threat of the Araucanians, she refused to withdraw. Soldier and poet Alonso de Ercilla recalls what happened in La Araucana:

She heard a great uproar, and was galvanised Grabbing a sword and a shield, she went after her neighbors as best she could… “Come back! … I offer myself here, to be the first to throw myself in the enemy irons!”

Remembered for her fortitude in helping found Guadalajara in western Mexico in 1542, Beatriz Hernández’s statue stands near the city’s Plaza Fundadores.

Alamy/ACI

Despite their courage, the surviving Spaniards had to take refuge in Santiago de Chile.

But the best known female soldier of the Spanish conquest of America is, without a doubt, Catalina de Erauso, also known as the Monja Alférez (Lieutenant Nun). As a teenager she escaped from a convent in San Sebastián, passed herself off as a boy, and served as a page for various illustrious figures. In 1603, at age 18, she boarded a ship in Sanlúcar and set sail for the New World. Once in Lima, she changed her name to Alonso Díaz. In 1606 she enlisted to fight the Araucanians (today’s Mapuche), who were closing in on the city of Concepción and the Valdivia fort in Chile.

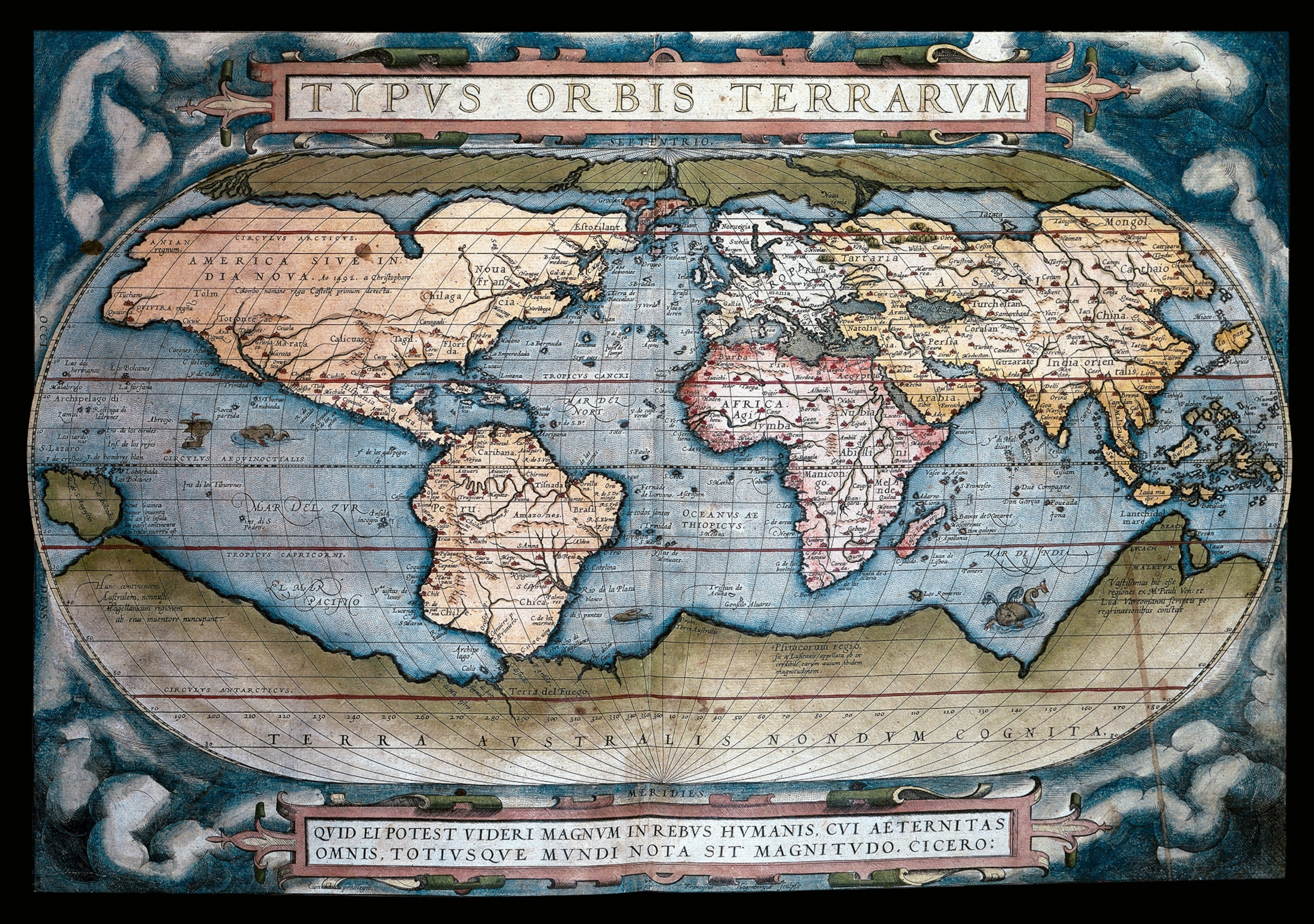

Abraham Ortelius’s 1574 world map, shown here, held by the Biblioteca de Catalunya, Barcelona.

Album

In one of the many battles during the war, the Araucanians killed the captain and lieutenant of Erauso’s company. Erauso and two soldiers jumped onto their horses and chased the group of Indigenous people who had seized the Spanish flag. With her two companions injured, Erauso continued the pursuit. She writes in her autobiography, “I, with a bad blow to the leg, killed the chieftain who was carrying it [the flag] and took it from him, and I pressed on with my horse, running over, killing and wounding countless; but badly wounded and run through with three arrows and a spear in the left shoulder … I fell from my horse.” She stayed in that place with some companions for nine months, after which she finally returned to the Spanish camp with the flag. It was then that Erauso obtained the rank of second lieutenant. She wasn’t granted the highest rank because she’d had the chieftain hanged instead of handing him over for questioning, as the governor had ordered.

A folding screen from the end of the 17th century is on display in Mexico City.

In her autobiography, Erauso tells how sometime later, after a brawl, she ended up recounting her life story to the bishop of Guamanga, near Cusco. “The truth is this,” she says. Having left the convent and changed her appearance to that of a man, “I embarked, contributed, brought stuff, killed, wounded, harassed, ran around, until coming to stop in the present at your most illustrious feet.” After two and a half years in a convent in Lima with the purpose of purging her crimes, the authorities allowed Erauso to return to Spain, since she clearly lacked interest in the religious life. Dressed as a man, she arrived in Cádiz on November 1, 1624, and was welcomed by cheering crowds. The king allowed Erauso to use the name Antonio instead of Catalina and provided an encomienda (a parcel of land manned by local laborers, who were not enslaved but often worked under abusive conditions) in Veracruz, Mexico. Antonio de Erauso died at the age of 65 in Cuitlaxtla, near the encomienda.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=6707b5e382214227a0702b1c27eee87d&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.nationalgeographic.com%2Fhistory%2Farticle%2Fwomen-conquistadoras-spain-america&c=5539123330859245058&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-10-10 00:06:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.