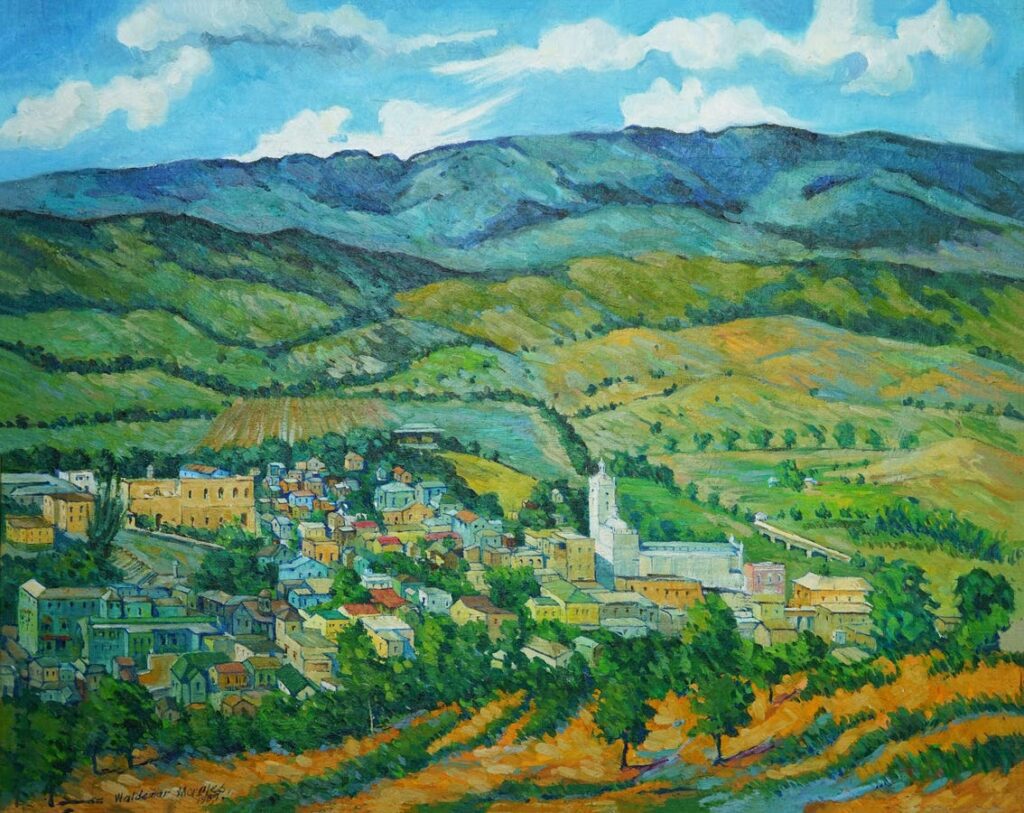

Waldemar Morales, ‘Landscape, View of San Germán (Paisaje, vista de San Germán),’ 1957. Oil on canvas. 25 11/16 x 32 (65.2 x 81.3 cm) 59.0118. Museo de Arte de Ponce. The Luis A. Ferré Foundation, Inc.

Museo de Arte de Ponce.

Van Gogh’s Arles. O’Keeffe’s New Mexico. Tom Thomson’s Canadian north woods.

Love letters in paint.

Seeing a place through the eyes of an artist who loves it provides insight and emotion. Feelings simple reproduction can’t capture.

So it was for a group of Puerto Rican artists active during the first six decades of the 20th century. Artists instrumental in developing a pictorial tradition on the island. Their love letters in paint can be seen through January 5, 2025, at the Rollins Museum of Art in Orlando during “Nostalgia for My Island,” a traveling exhibition from the renowned Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico.

Through their eyes, a picture emerges of Puerto Rico as an ideal nation.

“It is impossible not to perceive the sentiment of pride coming through these images of the Puerto Rican people, traditions, and the landscapes of the island,” Iraida Rodríguez-Negrón, curator, Museo de Arte de Ponce, told Forbes.com. “What these artists chose to highlight are more general than specific: human relationships, identity, the nation, and the land.”

Historical context explains why that is the case.

“This is a moment of transition for Puerto Rico, from one colonial power to another,” Rodríguez-Negrón explains. “In these works, we see the longing of the people, through the eyes of the artists, for what they considered to be the essence of being a Puerto Rican, perceived as being under threat by foreign powers.”

Following the Spanish-American War in 1898, Puerto Rico exchanged the yoke of Spanish colonialism for the yoke of American colonialism.

Christopher Columbus arrived in 1493, one year after landing on what is present day America. Genocide of the Indigenous Taíno population and plantation slavery followed in an eerily similar blueprint for colonization. Spain would control the island for 400 years. Slavery, as an aside, was only outlawed there in 1873.

Still, the devil you know can be preferable to the devil you don’t, and Puerto Rican artists were–rightly–leery about the pending transition.

“We also perceive this sense of nostalgia (in the artworks), as the title of the exhibition highlights, nostalgia for that which might be lost through assimilation,” Rodríguez-Negrón said.

America asked Puerto Rico for assimilation, but it was not–has never been–a two-way street. Puerto Ricans weren’t granted American citizenship until 1917, a measure largely undertaken by U.S. politicians to bolster draft candidates for World War I.

America’s historical interest in the island extends as far as Puerto Rico’s natural resources and labor force can be exploited by American corporations. When Hurricane Maria–a category four monster storm–struck the island in 2017, killing some 3,000 people, the Trump Administration’s response was to essentially turn its back on the U.S. territory. Puerto Ricans might view it as giving a middle finger.

The island has yet to fully recover.

Nostalgia For My Island

Rafael Ríos Rey, ‘Party during Christmas Season (Fiesta navideña),’1941. Oil on canvas, 26 1/4 x 19 1/8 in (66.7 x 48.6cm) 98.2242. Museo de Arte de Ponce. The Luis A. Ferré Foundation, Inc. Gift of Luis A. Ferré.

Museo de Arte de Ponce.

“Nostalgia for My Island: Puerto Rican Painting from the Museo de Arte de Ponce (1786–1962)” presents for the first time outside Puerto Rico a selection of 21 artworks by some of the most important artists in the island’s art history. At the behest of the National Museum of Puerto Rican Arts and Culture in Chicago, where the exhibition originated, several paintings by José Campeche (1751-1809) and Francisco Oller y Cestero (1833-1917), who are recognized by many as the first masters of Puerto Rican painting, are included in the show, giving the presentation its nearly 300-year sweep. Interestingly, Puerto Rican painting went largely unchanged through that epoch.

“The parenthesis closes at mid-century. At that time, a significant transformation happened in Puerto Rican art, especially due to the return of young artists who had the opportunity to train outside the island in important artistic centers such as New York City, Mexico City, and Madrid,” Rodríguez-Negrón said. “In the mid-century, we see an influx of more international styles like abstraction and social and political critique, the latter becoming one of the main themes of Puerto Rican painting in the period after the one covered in ‘Nostalgia.’”

Organized around three main themes, “My Home,” “My People,” and “My Island,” the exhibition explores popular subjects in Puerto Rican art during the first half of the twentieth century.

“During the period of the exhibition you see the artists highlighting the figure of the jíbaro, the country folk that worked the land, which during the 19th century became an icon of the ‘Puerto Rican-ness,’” Rodríguez-Negrón explains.

Most of this era’s artists were committed to preserving Puerto Rican identity, an identity they felt was being threatened by the political changes taking place because of the transition from Spanish colonial rule to American. This sentiment was perfectly expressed by Miguel Pou y Becerra (1880-1968), an artist born in Ponce and featured in “Nostalgia for My Island,” when he stated, “…an artist is a true patriot who fights and strives to leave for his homeland the legacy of his dreams… The ideal that has mainly oriented my work has been to represent the soul of my country.”

The “soul” of a place.

Revealed only to intimates, lovers.

What van Gogh shared of Arles, O’Keeffe New Mexico, Thomson the North Woods, and the artists in “Nostalgia for My Island” for Puerto Rico.

“It has been beautiful to see how audiences, particularly those from the Puerto Rican diaspora in the US, have connected so easily and deeply to the works in the exhibition,” Rodríguez-Negrón said. “The sense of nostalgia for that which they had to leave behind—their people, their home, and their island—is really moving and powerful. It is an essence of humanity to which any displaced person can connect to.”

Following the presentation at Rollins, the exhibition will be on view at its home institution, Museo de Arte de Ponce, on Puerto Rico’s southern coast, following the museum’s renovation.

Around Orlando

Melissa Menzer, ‘Full Moon.”

Melissa Menzer and Jeanine Taylor Folk Art

Orlando’s cultural community–all of it–was nationally disgraced in 2022 when the Orlando Museum of Art–it’s signature institution–exhibited fake Jean-Michel Basquiat paintings. An FBI raid, scorn, and humiliation rightly followed. For a city trying to tell the world it has more to offer than amusement parks, the scandal reinforced stereotypes it doesn’t.

As the OMA attempts to unbury itself from the shame, efforts like its fall 2024 exhibition schedule will help rebuild trust. The museum offers a variety of humble, intriguing, and unexpected presentations.

On view are over sixty masterpieces of original illustrations from the Little Golden Books series including pieces from beloved picture-book classics like “The Poky Little Puppy,” “Tootle,” “Home for a Bunny,” “The Color Kittens,” and “I Can Fly.” Launched in 1942, Little Golden Books made high quality illustrated books available at affordable prices for the first time to millions of young children and their parents.

Rock-and-rollers will appreciate “Torn Apart: Punk + New Wave Graphics, Fashion and Culture,1976-86,” bringing together for the first time Andrew Krivine’s extensive collection of punk graphics and ephemera, Malcolm Garrett, MBE’s collection of Vivienne Westwood garments, and Sheila Rock’s photography, along with an exhibition of live music photography spanning Janis Joplin to Lauryn Hill through the lens of Larry Hulst.

Finally, an exhibition of skateboarding photography from the 1980s proves plenty of blue sky exists in attracting mainstream audiences to art museums beneath the “blockbuster” show.

For art from and about Florida, anyone making the 25 mile drive north of Orlando to charming Sanford will be rewarded beginning October 12 with a show of home grown folk art themed to “Florida Gothic” at Jeanine Taylor Folk Art. Think gators and frogs and snakes and swamps and things that go bump in the night.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66f9577d31304f68af3a7e8df79beb56&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.forbes.com%2Fsites%2Fchaddscott%2F2024%2F09%2F29%2Fvisual-love-letters-to-puerto-rico%2F&c=17530820518225790377&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-09-29 02:30:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.