Small company, big goals

Two people act as the face of Terra Invest. Ruud Souverein is a Dutch businessman living in Suriname, a former Dutch colony, and has a background in marketing, agribusiness and processed foods. Adrián Barbero, who bills himself as “the first developer of Mennonite projects in Suriname and Guyana,” is an Argentinian real estate entrepreneur and farmer living in Santa Cruz, Bolivia, where he has spent the past 20 years brokering land deals with Mennonite and other farmers.

Barbero said he considers Mennonites to be his friends. He said he wants to help them navigate the legal system, escape religious persecution, and find better economic opportunities. As some Mennonite communities have grown in Latin America, younger generations haven’t been able to establish farms with the same success. He said starting new colonies in Suriname might fix the problem.

“They’re young people who no longer have land in other countries,” Barbero told Mongabay. “[In Suriname], they can resettle their lives with a piece of land.”

Barbero has curated his social media presence to come across as a champion of the Mennonites, even calling himself an “agro-influencer” while posting on Facebook and TikTok about new farming projects and efforts to expand. Mennonites themselves traditionally don’t use modern technology.

In one video, he shows Mennonites on a ferry crossing a river in Guyana. In another, he’s shopping for heavy farming machinery in Suriname.

Barbero with Mennonites during a trip through Suriname. (Photo courtesy of Adrián Barbero)

Barbero with Mennonites during a trip through Suriname. (Photo courtesy of Adrián Barbero)

Once Mennonites are settled in Suriname, Barbero said their farms could grow corn and soybeans to meet the domestic demand for chicken feed. Poultry is traditionally Suriname’s most-consumed meat product, but rising prices on the global market have made it harder to obtain. Domestically grown feed could help lower the price and improve food security, Barbero said.

He’s also working on finding seed suppliers. Brazil isn’t an option because it uses genetically modified seeds and grows them using the herbicide glyphosate, which is banned in Suriname. He said he expects to import seeds from a company in the U.S. or Europe that will be more easily approved by Suriname’s Ministry of Agriculture.

Terra Invest has already been in contact with the ministry, Barbero said. The ministry didn’t respond to Mongabay’s interview request.

Following the letter of the law as closely as possible, which hasn’t always been the case for Mennonite farmers, is a priority for Terra Invest, Barbero said. The company will also carry out environmental impact studies and take steps to ensure the Mennonites have as little ecological impact as possible. They plan to clear only 50% of the land, he added.

“We want to make sure the legal framework is correct,” he said. “We’re working within an interesting legal framework and we proposed that we make as little impact as possible.”

Mennonites visiting a farm during a trip through Suriname. (Photo courtesy of Adrián Barbero)

Mennonites visiting a farm during a trip through Suriname. (Photo courtesy of Adrián Barbero)

Government and NGOs on edge

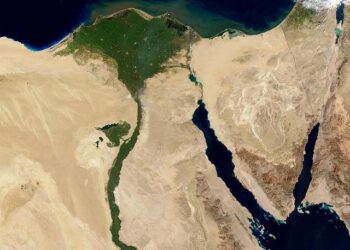

More than 90% of Suriname is covered by the Amazon Rainforest. The country has struggled with gold mining over the years — both a top export earner and a main driver of deforestation — but overall it’s managed to avoid the kind of economic development that might compromise its forests.

It’s one of just three countries with a carbon-negative economy, meaning its forests absorb more carbon dioxide than the country emits — a huge help in the fight against climate change.

But the government is also facing a financial crisis. A growing fiscal deficit and high inflation have forced it, among other things, to restructure its debt with the IMF. High costs of living and food scarcity caused by floods have sparked nationwide protests. The need for revenue is at an all-time high, and agricultural production sounds appealing to some lawmakers.

“If you need development, there are consequences,” Gregory Rusland, a representative in the National Assembly and former minister of natural resources, told Mongabay. “We’re keen on maintaining our nature, but at a certain point you need food production.”

Mennonites in the San Rafael municipality of Santa Cruz, Bolivia. (Photo by Judah Marsden/ACT)

Mennonites in the San Rafael municipality of Santa Cruz, Bolivia. (Photo by Judah Marsden/ACT)

President Chan Santokhi, a former police chief who took office in 2020, tried to strike a balance between conservation and the economy when he proposed selling carbon credits under a framework established by the 2015 Paris Agreement. The plan would keep the country’s trees in the ground while generating some much-needed revenue.

But Santokhi has also expressed interest in the Mennonite pilot project approved by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, despite the Mennonites’ history of encroaching on projects tied to carbon credits, such as protected areas and Indigenous territories.

Suriname is the only Amazonian country that hasn’t legally recognized Indigenous land rights. The idea that the government is negotiating with foreign Mennonite farmers while Indigenous people still go unrecognized has frustrated many local communities as well as members of the National Assembly, who have spent years pushing for a vote on the issue.

“We don’t have our land rights,” said Iona Edwards, an Indigenous Lokono serving in the National Assembly. “You can’t bring another group into our community where we already are expecting help from the government.”

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Natural Resources didn’t respond to a request for comment for this story.

Mennonites during a visit to Suriname. (Photo courtesy of Terra Invest/Facebook)

Mennonites during a visit to Suriname. (Photo courtesy of Terra Invest/Facebook)

Some conservation groups have been slowly mounting a campaign against the Mennonite land purchases. Last week, many of them met to discuss potential environmental risks, including damage to nearby wetlands and surrounding rice fields.

But other groups, especially those working internationally, have taken a more conservative, if not silent, approach to the Mennonite negotiations. Because they work closely with the Surinamese government, they’ve decided to wait and see what officials will do. Others have tried expressing their concerns through back channels.

In general, they say they hope the Mennonite farmers stay out of the country altogether. The arrival of even a small group of Mennonite farmers has been shown to result in widespread deforestation.

WWF, which had a meeting with Terra Invest in August, said it respects Suriname’s decision to allow Mennonites into the country, but said farming should only be done on already degraded land.

“If large-scale agriculture begins to occur on intact forest landscapes, as opposed to already degraded lands, Suriname will have a very big difficulty in maintaining its forest cover,” said David Singh, director of WWF Guianas.

Banner image: Photo via Terra Invest/Facebook.Â

Editor’s Note: David Singh’s title has been corrected. He’s the director of WWF Guianas, not WWF Guyana.Â

FEEDBACK:Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

See related from this reporter:

How Canada’s growing presence in Latin America is hurting the environment

agribusiness, Agriculture, Amazon Agriculture, Climate Change, Conservation, Deforestation, Environment, Environmental Law, Environmental Politics, Forests, Governance, Indigenous Peoples, Indigenous Rights, Industrial Agriculture, Migration, Rainforest Agriculture, Rainforest Conservation, Rainforest Deforestation, Rainforest Destruction, Rainforests, Threats To Rainforests, Tropical Forests

Belize, Bolivia, Latin America, Mexico, South America, Suriname

Source link : https://news.mongabay.com/2023/10/plan-to-bring-mennonite-farmers-to-suriname-sparks-deforestation-fears/

Author :

Publish date : 2023-10-09 03:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.