“Any understanding of this nation has to be based on an understanding of the Civil War,” the late historian Shelby Foote observed. It “defined us as what we are, and it opened us up to what we became.” The American Civil War set the United States on the path to becoming a global force, but another clash, long forgotten, enabled America to become a continental power.

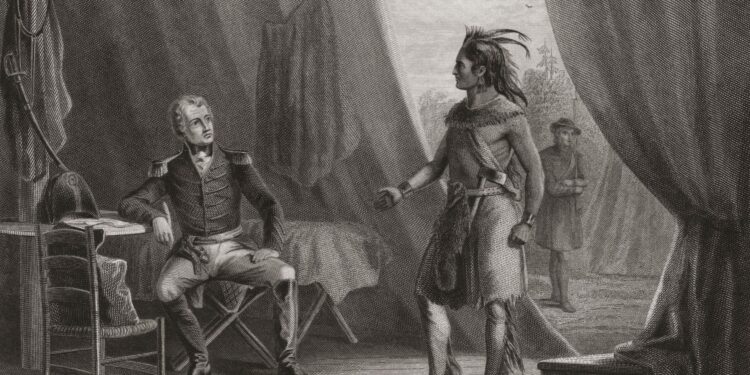

The Creek War is little known to most Americans today. In some respects, this is unsurprising. The conflict lasted a little more than a year and unfolded against the backdrop of another overlooked conflagration, the War of 1812. Yet, the war was key to forging both the American character and the United States itself. What began as an internecine struggle between Creek Indians made America what it is today.

“No other Indian conflict in our nation’s history so changed the complexion of American society as the Creek War,” the author Peter Cozzens observes in his new book, A Brutal Reckoning: Andrew Jackson, the Creek Indians, and the Epic War for the American South. It was, he notes, “the most pitiless clash between American Indians and whites in U.S. history.”

The Creek Confederacy’s loss ensured the end of their way of life. And the victory by U.S. forces, led by future president Andrew Jackson, gifted the United States with 22 million acres of land in Alabama and Georgia.

American policymakers at the dawn of the Republic confronted a security environment that is hard to imagine today. The United States as we now know it didn’t exist. The French, Spanish, and British had territorial and commercial holdings on the continent, with the latter two even possessing sizable military garrisons. By contrast, the United States didn’t possess a standing army and its new navy was a hodgepodge of ships. Many doubted whether the U.S., with its revolutionary form of government, would endure. Indeed, many of the European courts were betting otherwise.

As President, Thomas Jefferson singled out his greatest national security concern. “There is on the globe a single spot, the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy,” he wrote. “It is New Orleans.” The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 eased Jefferson’s concerns about foreign influence, but it didn’t eliminate them. Jefferson believed that America’s future lay in the West, but he also recognized the need to have “defense in depth” against European powers. As former U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick observed in his book America in the World: “Security required settlement.” And that settlement was certain to be bloody.

The war began amongst the Creeks themselves.

The Creeks, Cozzens points out, “Lived in a land of abundance,” with vast territorial holdings that were, the American Indian agent Caleb Swan noted in 1791, “remarkably healthy.” The country, Swan wrote, “must become a most delectable part of the United States…and one day or other be the seat of manufacturers and commerce.”

The Creeks were aware that their lands were coveted by foreigners. Indeed, their own kingdom stood in what was the center of a struggle for empire between Great Britain, Spain and France, at one point comprising half of the present-day Deep South. They tried to play the three powers off one another.

Yet ultimately, the Creek policy of studied neutrality was doomed to fail. America was going to be conquered and settled, either by one of the European nations or by the settlers themselves.

Over time, the British gained an advantage with the Creeks. The French were unable to compete economically, the Spanish empire was already in the throes of a centuries-long decay, and the British had steadily expanded trade with the Creeks.

After the American Revolution, Georgia’s population more than doubled, leading to an influx of settlers at the veritable heart of the Creek nation. A recent war with the Choctaws, a proxy of the French, had gone poorly. Fissures soon developed in Creek society, with the rise of pro-American and pro-British factions. Further complicating matters, the Creeks had decentralized rule—a boon for their enemies. “Young Creek warriors bridled at their elders’ passivity,” Cozzens notes.

The Creeks were both divided and adrift when the Shawnee leader Tecumseh, and his brother Tenskwatawa, known as the Prophet, attended the annual Creek council in 1811 in present-day Alabama. Both Shawnee men preached war against the Americans, converting a number of Creek religious leaders in the process. They would soon become known as the “Red Sticks” Their opponents were known as the “White Sticks,” and largely hailed from the Lower Creeks, who tended to trade more with the Americans. The two were soon at war.

The Red Sticks began attacking their opponents, launching the first major offensive in July 1813. The War of 1812 raged in the backdrop, with the U.S. and Great Britain first coming to blows a year before. The Red Sticks cast their lot with the British.

On August 30, 1813, Red Stick chiefs Peter McQueen and William Weatherford led an attack on Fort Mims, 50 miles north of Mobile. A slave had told the fort’s commander, Dixon Bailey, that he had seen the Red Sticks gathering. However, the disbelieving Bailey had the man whipped as a liar. Accordingly, the gates were open when 1,000 of the Sticks attacked. Bailey was among the first to fall. Nearly all of the fort’s inhabitants were slaughtered—no fewer than 553 men, women and children, and many in the most brutal fashion imaginable. According to one account: “the children were seized by the legs and killed by battering their heads against the stockading, the women were scalped, and those who were pregnant were opened while they were alive, and the embryo infants let out of the womb.” What became known as the Fort Mims Massacre drew national outrage, briefly focusing popular attention away from commensurate battles against the British. The massacre had another important side effect: it brought Andrew Jackson into battle against the Red Sticks.

Jackson, Cozzens notes, “provides a stunning lesson in how the unwavering will of one man could set the course of a crucial era of American history and almost single-handedly win what was arguably the most consequential Indian war in U.S. history.”

Born into poverty in 1767 in the Carolinas (precisely which Carolina is still a matter of debate), Jackson had a rough early life. His father died before he was born, and both of his brothers and his mother would die during the American Revolution. Nonetheless, Jackson reached great heights, becoming a prosperous attorney and landowner, as well as a judge and, briefly, a member of Congress. Jackson represented a new breed of American: self-educated, without a trace of blue blood, and born on the treacherous frontier, far from the sanctity of New York, Philadelphia and the remnants of the “Old World.” An accomplished duelist with a fierce temper and an undying hatred for the British, Thomas Jefferson considered Jackson a most “dangerous man.” Indeed, Jackson was recovering from a wound suffered during a gunfight on Nashville’s city streets when word of Fort Mims reached him. His arm still in a sling, Jackson hurried south.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

In November, Jackson destroyed the village of Tallushatchee, and a week later, won a battle at Talladega, killing an estimated one-third of the assembled Red Sticks. But the decisive engagement came at Horseshoe Bend, a formidable defensive coastal encampment that Jackson took at great cost. “After that, it was simply a matter of using terror—burning villages, destroying crops—until the Indians had decided that they had had enough,” Johnson notes. Weatherford, known as Red Eagle, surrendered to Jackson on April 14, 1814, and by August the war against the Red Sticks was over.

The Creek War was a proving ground for the men who built America in the mid-nineteenth century. As Paul Johnson observed, the “men who were later to expand the United States into Texas and beyond were bloodied in the Creek War.” Jackson’s onslaught against the Red Sticks won him both a promotion and subsequent command during the Battle of New Orleans, where his victory against the British made him a national icon, paving the path to the presidency. Men who served under Jackson, such as Sam Houston and Davy Crockett, would themselves become national figures. The men who fought Tecumseh up north would also gain fame, with William Henry Harrison becoming the ninth president of the United States, and Richard M. Johnson, allegedly the man who killed Tecumseh, becoming a senator and vice president.

The Creek War birthed no fewer than a dozen political careers. But more importantly it enabled the nation’s rise. The massive amounts of land taken from the Creek put the U.S. on the path to becoming a continental power and set the stage for the wars, both against Mexico and ourselves, that followed. The Civil War may have been the “crossroads of our being” as Shelby Foote put it, but that road was paved decades prior in a brief and bloody conflict in America’s south.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=6716464977194bfea8e089d528db6ce0&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.theamericanconservative.com%2Fthe-forgotten-war-that-made-america%2F&c=7965468986907556260&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-10-16 17:15:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.