Which survey offers a better picture? Back in June, Bloomberg’s chief economist Anna Wong suggested the establishment survey is suspect, writing: “We believe the [household survey] currently offers a closer approximation of reality than [the establishment survey], as BLS’ model for estimating business births and deaths … is lagging the reality of surging establishment closures and falling business formation.”Â

(In August, that birth-death model added 100,000 jobs to the payrolls total.)

Assuming that the establishment survey is a realistic picture of the economy at all, then the current economy is producing many more jobs than actual workers.Â

A Recession in Full-Time Jobs

The economy is apparently adding far more part-time jobs than it is adding full-time jobs. In fact, the economy is rapidly shedding full-time jobs, and full-time job measures point to recession.

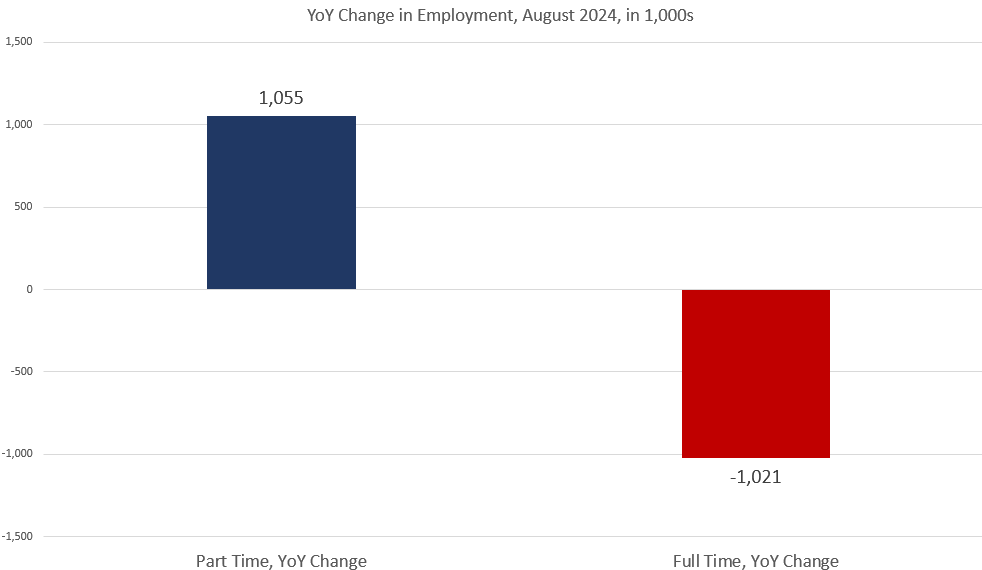

Over the past year, for example, total part-time jobs increased by 1.05 million. During the same period, full-time jobs fell by 1.02 million. In other words, net job creation during that period has been virtually all part-time. In the month of August alone, workers reported a gain of 527,000 part-time positions while full-time jobs fell by 438,000.

Â

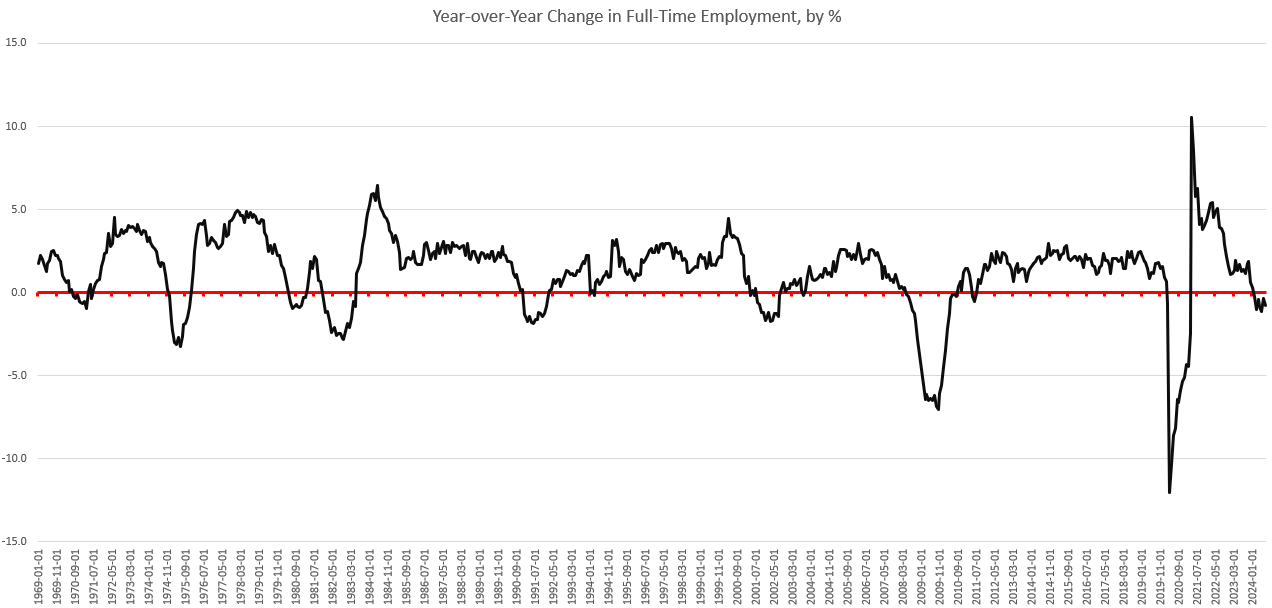

Year over year, total full-time employees fell 0.8 percent. Over the past five months, in fact, the year-over-year measure of full-time jobs has been in recession territory. Full-time jobs have now been down, year over year, in every month since February. Over the past fifty years, three months in a row of negative growth in full-time jobs has always been a recession signal and has occurred when the United States has been in recession, or about to enter a recession:

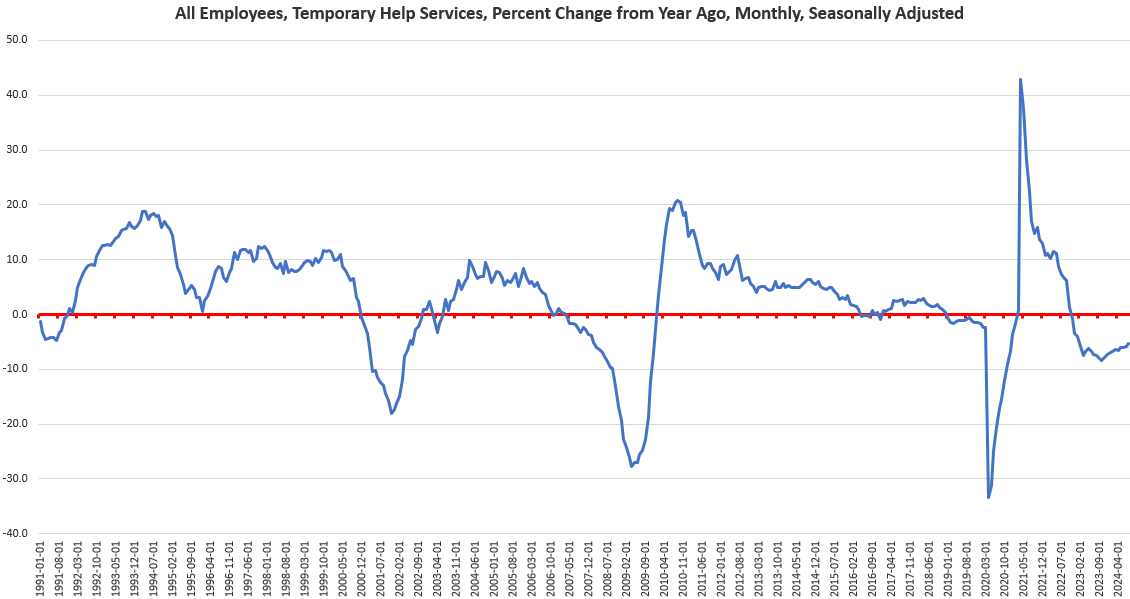

The full-time jobs indicator now reflects what we’ve seen in temporary jobs for months. For decades, whenever temporary help services are negative, year over year, for more than three months in a row, the US is headed toward recession. This measure has now been negative in the United States for the past twenty-two months. Temporary jobs in August were down by 5.2 percent.Â

Not surprisingly, other measures of employment point to a weakening economy. For example, in contrast to the headline unemployment rate, August’s U-6 measure of under-employment rose to 7.9 percent, a 35-month high, Job openings in the construction sector have experienced a historic collapse, dropping from 456,000 in February 248,000 in August.Â

If we take a larger look around, we find plenty of worrisome data in the leading indicators: The Philadelphia Fed’s manufacturing index is in recession territory. The same is true of the Richmond Fed’s manufacturing survey. The Conference Board’s Leading Indicators Index continues to point to recession. The yield curve points to recession. Net savings has now been negative for six quarters in a row. (That hasn’t happened since the Great Recession.) The economic growth we do see is being fueled by the biggest deficits since covid.Â

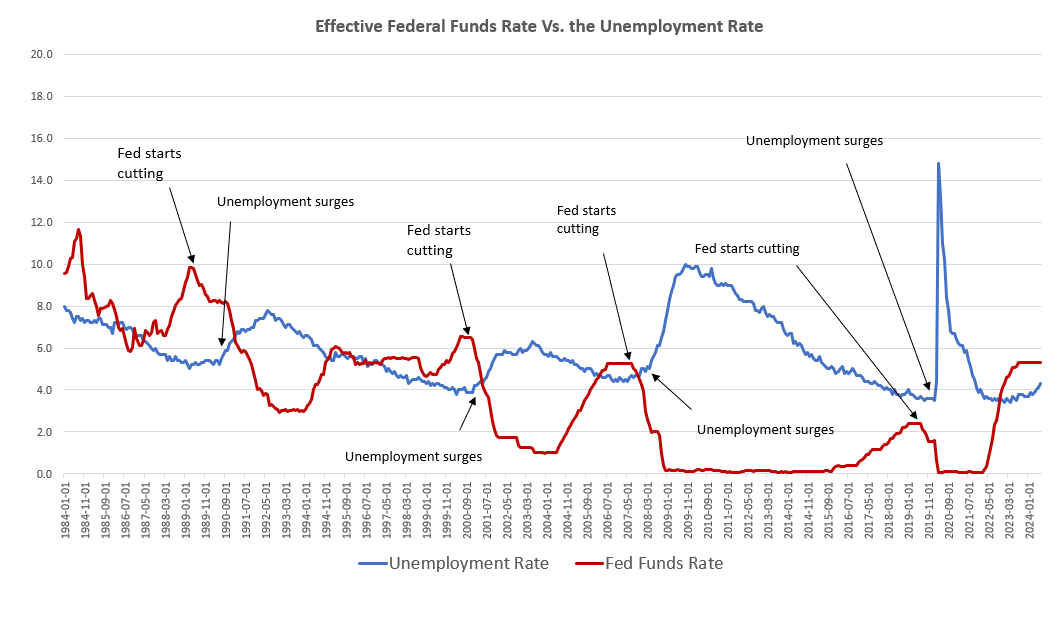

Having accepted that the economic and employment outlook is hardly positive, the debate is now over how much the Federal Reserve’s FOMC will cut the target policy interest rate at the FOMC’s September meeting. Ever since July’s jobs report, Fed policymakers have repeatedly signaled they plan to cut the federal funds rate soon. This, however, only points all the more to an impending recession. Recessions usually follow Fed rate cuts.Â

In spite of continued claims that the Fed will “engineer” a “soft landing,” the Fed has never succeeded in doing so. Ever.Â

The Fed’s lack of success in this regard isn’t because the Fed is unlucky or bad at timing its rate cuts. The problem stems from the fact that in situations like we are now in, the Fed only has two policy choices: it has to choose between rising price inflation or recession.Â

Experience shows that the Fed tends to prefer price inflation, and the Fed would rather force down interest rates and pursue easy-money policies all the time. The reason the Fed can’t do this is because easy-money policies cause place inflation, which often becomes a political problem for the regime.Â

So, when price inflation rises to politically unsustainable levels, the Fed must allow interest rates to rise and cut back on its easy-money policies. But, as Mises showed, an easy-money-addicted economy (such as the one we are now in) will enter the bust phase of the business cycle once there is less new money entering the economy. The only way the Fed can prevent a continued worsening in economic conditions right now is to turn back to easy money and again flood the economy with liquidity. However, the economy is now barely past a period of historically high levels of monetary inflation—i.e., “money printing.” A return to easy money will cause a new surge in rising prices. This is what happened in the 1970s during the Arthur Burns years. The Burns Fed tried to create a soft landing, but only succeeded in creating stagflation.Â

These are the options the Fed now faces. There is no soft landing coming.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66dba21f5d5648d5a7cfc8fb352f0742&url=https%3A%2F%2Fmises.org%2Fmises-wire%2Famerica-now-has-fewer-employed-workers-it-did-year-ago&c=15900481232653771809&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-09-06 11:29:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.