Florida abortion ban sends Palm Beach County woman to Illinois

The Palm Beach County woman couldn’t get the healthcare she needed to end her pregnancy in Florida. So she traveled 1,200 miles to where it was legal.

Florida’s ban on abortions after six weeks from a woman’s last menstrual period made the procedure inaccessible in the state for most women seeking to terminate their pregnancies.

With or without financial assistance, patients seeking abortion care cross multiple state lines, often alone, on costly journeys to unfamiliar cities where abortion is still legal, but where the incidence of violence and harassment of abortion providers and patients has risen steeply since Roe v. Wade was overturned.

To share the experience of one patient affected by Florida’s abortion restrictions, Palm Beach Post Staff Writer Antigone Barton accompanied a young woman who left her home and family in Palm Beach County to travel out of the state for abortion care. To maintain her privacy, she is referred to here by the fictitious name of Sarah. Sarah’s journey took her to Illinois, where abortion rights are protected by law. Â

The very young woman waiting near the departure gate, in T-shirt and leggings, a worn knapsack at her feet, could have been a college student, heading back to school after a visit home.Â

She waved me over.Â

Sarah is on the line between girl and woman.  She looks like she knows what she’s doing. Most of the time she probably does. She has an air of calm composure. Â

She has a smile that makes other people smile. Â

She has not lived long enough yet to guess how things might go wrong.Â

The story Sarah had told members of her family to explain why she needed a ride to the airport had fallen apart the previous night with 11 hours to go before boarding a plane.Â

She had not thought telling them the truth would help. The truth was that she had gotten pregnant and was going to get an abortion that was now illegal in the state she and her family call home.Â

She never told me exactly what happened that night, but at midnight she had texted me to say the trip was off. Â

Then, a little after 5 a.m., she called to say she was going after all. Â

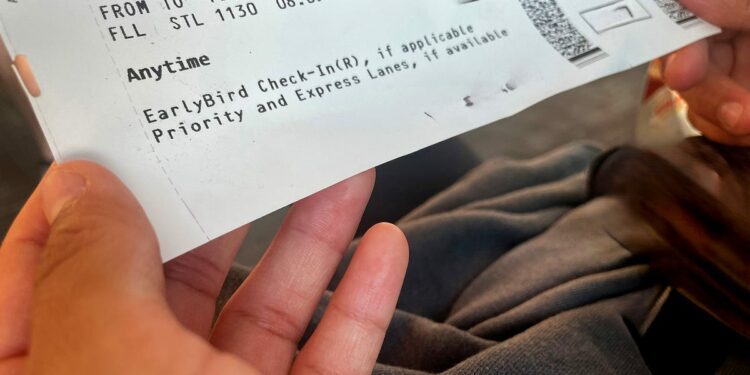

A member of her family dropped her off at the airport in Fort Lauderdale, an hour from their home, before dawn.Â

“Everyone knows now,” she said.Â

She meant everyone in her family. Â

She was more than 19 weeks pregnant. Over the next four days, she would undergo three procedures to end her pregnancy. After each, she would return to a hotel room, where for the first time in her life she would be staying alone. She had never traveled without her family.Â

Like thousands of women who in the past two years have traveled far from home to get the medical care they needed, she faced a strenuous, stressful and scary journey.Â

More: As Florida six-week ban forces women to leave state for abortions, volunteers add support

When abortion care became a question of geographyÂ

The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in 2022 to rescind the half-century-old right to abortion care instantly triggered restrictions across the country, making the procedure illegal in some states or so restricted as to be out of reach for most women in others.Â

Florida’s law narrowing the time in which a doctor could perform an abortion to within 15 weeks after the patient’s last menstrual period went into effect soon after the Dobbs v. Jackson decision. It forced patients to travel out of state for abortions that required multiple procedures spanning several days.

More: Providers prepare for perils of new 6-week abortion ban that starts Wednesday

More than 90% of abortions nationwide take place well before 13 weeks of gestation. Very young women are the likeliest to have an abortion later in pregnancy because they don’t detect the pregnancy sooner or find their way to care.Â

Florida’s ban on abortions after six weeks from the first day of a woman’s last menstrual period went into effect in May. It closed abortion access in the final Southern state. Â

“It was devastating,” said Brittany Fonteno of the National Abortion Federation.  Â

In the two months after Florida’s six-week ban went into effect, the organization’s hotline alone helped nearly six times as many patients travel out of state for care as the same two months the year before.Â

Many women do not discover they are pregnant within six weeks. Not all women have menstrual cycles that are reliably regular. A cycle of more than four weeks is not unusual.

In addition, a Florida law that went into effect following Dobbs requires patients seeking abortions to visit a clinic and then come back 24 hours later before the procedure. The first time is to be informed of “alternatives” — information about charities, social services and adoption agencies for assistance with the one other choice facing a woman seeking an abortion: bringing an unintended, unwanted or unsafe pregnancy to term and giving birth.Â

For growing numbers of patients, getting the care they seek is preferable to what Florida calls the “alternatives.”Â

Nationwide, the number of abortions has risen since the Dobbs decision.Â

Too sick to work: How Sarah found out she was pregnant Â

Sarah was looking forward to college. She plans to maybe major in business and also take psychology classes. She hopes to run her own business someday. Â

First after graduating from high school, she wanted a year off from formal education to enjoy the independence of earning her own money.Â

She had a retail job and loved it. She smiled when she named the business where she had worked, until she got too sick to work.Â

“At first I thought I had food poisoning.”  She couldn’t stop vomiting – for weeks. She couldn’t keep water down.Â

She had never experienced anything like this. Â

At her local hospital, she was given fluids through an IV. She could not take pills to stop the vomiting because she couldn’t keep them down. Â

She learned she was pregnant when she was in the hospital.Â

Sarah had hyperemesis, a complication that affects 1% to 3% of pregnant women. Unlike normal “morning sickness,” the nausea and vomiting that can accompany early pregnancy, it can cause death from dehydration.Â

Charlotte Bronte, the Victorian-era novelist who wrote “Jane Eyre,” died at age 39 from hyperemesis in 1855. In recent years, Catherine, Princess of Wales, was hospitalized due to the condition during her pregnancies.Â

Hyperemesis can be completely incapacitating, Sarah’s physician said. “You can’t get out of bed.”Â

By the time Sarah sought an abortion at the Presidential Women’s Center in West Palm Beach, she was 19 weeks pregnant. Â

The Presidential Women’s Center arranged for her to find the care she needed in Illinois to end a pregnancy that was harming her and that she was not prepared to sustain.Â

A West Palm Beach clinic’s role shiftsÂ

The Presidential Women’s Center was founded more than 40 years ago to expand abortion access for women living in Palm Beach County.Â

Since the six-week ban took effect in May, the clinic continues to treat patients within the parameters of the law and works with clinics in states where abortion rights are still protected to find care for those who can no longer be treated in Florida. Clinic staff works with the Emergency Medical Assistance fund, a nonprofit started in the 1970s to help women of limited financial resources get to and pay for abortions. The fund now provides money for airfare, lodging and meals.Â

Inspectors from Florida’s Agency for Health Care Administration, which regulates abortion providers, come regularly to pore through patient records and confirm that no fewer than 24 hours have passed since a patient’s initial visit for “counseling,” before returning for the procedure itself.Â

More: Palm Beach County lawyer sues DeSantis, says he’s abusing his power on abortion amendment

The center has always offered counseling and referrals to patients for whatever decision they make.Â

Sarah had made her decision before she came to the center, and it never changed. She was not ready to become a parent.Â

The other person involved in Sarah’s pregnancy – the “co-conceiver” in current parlance – was no longer part of her life.Â

‘What are you in town for?’Â

Sarah’s ankles were crossed, and her feet swung over the pavement beneath the bench where we waited for an Uber, the long shoelace of her sneaker grazing the ground.Â

The Uber had been arranged when we landed in St. Louis, Missouri through the Regional Logistics Center, a nonprofit that operates from a nearby Planned Parenthood office.Â

The local Planned Parenthood and the Hope Clinic in southeastern Illinois had formed the Regional Logistics Center in 2019 in the face of growing abortion restrictions in surrounding states. Since the overturn of Roe, it has served as a modern-day underground railroad for nearly 10,000 women traveling to the area for care since then. It works with agencies that book ride shares and hotels to help women find their way to clinic appointments and lodging.Â

Sarah got instructions on her phone after we landed at the airport in St. Louis, Missouri. We went to Passenger Pickup where a car would arrive and take us straight to the clinic, just over the border in Illinois.Â

The driver pointed out the city’s iconic Gateway Arch, as he pulled onto the bridge, leaving St. Louis, a vibrant city of historic landmarks, restaurants and nightlife, behind us. We headed over the Mississippi River toward Granite City, a small town of abandoned businesses where the population had declined by more than a third in recent decades.Â

Home to two long-established clinics providing abortions, Granite City lies in the southeastern tip of Illinois, surrounded by states, including Missouri, where abortion is illegal. Â

When Illinois enshrined abortion as a “fundamental right” with its 2019 Reproductive Health Act, Granite City became a well-known destination for patients seeking care from miles around. The majority of local voters, however, pick candidates opposed to abortion rights.Â

“What are you in town for?” he asked.Â

“For work,” I said.Â

Sarah, looking out the window at the unfamiliar wide-open green landscape with scattered, paint-faded low-lying wooden houses and shuttered stores, stayed silent.Â

Hope Clinic: ‘Where there’s hope, there’s choice’Â

Hope Clinic, built at its current location in the 1990s expressly for the purpose it serves, looks a little like a fortress. It has no windows on the first floor. An enclosure for security guards juts out next to the front door.Â

A banner hanging against the front wall welcomed us: “Where there’s hope, there’s choice.”Â

The clinic was founded at another Granite City location in the 1970s by a local doctor. The place made national headlines in 1982 when abortion opponents calling themselves “Army of God” kidnapped the doctor and his wife, holding them captive for a week. The group also took credit for setting two Florida abortion clinics on fire.Â

Since then, Hope Clinic has been the site of harassment directed at staff and patients, leading to arrests of protesters. Statewide, anti-abortion vandalism, obstruction and violence have increased since the overturn of Roe.Â

When we arrived, the street around the clinic was empty and quiet. Â

A security guard stepped out of the guardhouse next to the front door, took our IDs and confirmed Sarah’s appointment. She searched our bags and scanned us from neck to toe with a metal detector.Â

A receptionist behind a thick glass enclosure in the lobby checked our IDs again. A framed T-shirt printed with “Just Say Roe” and autographed by actress Whoopi Goldberg hung over her desk.Â

Affirmation lines the walls, with framed posters saying, “Shout your abortion” and “Together for Abortion” hanging over the stairway we climbed to the second floor. At the top we pushed a button to be buzzed in.Â

A trio of front desk staffers welcomed us, working without interruption as they answered phones, led patients to examining rooms and gave Sarah a clipboard of papers to fill out. She retreated to a corner where a sign next to the phone charging station said, “Abortions are normal.”Â

A half dozen women scattered around the waiting room also filled out papers.Â

Sarah took the papers to a staffer at the desk. A nurse led her to the back.Â

Sarah would be at the clinic for about four hours to be examined and educated about that day’s and the next two days’ procedures.Â

I headed out to look for lunch in downtown Granite City. A McDonald’s, a Taco Bell and a Walgreens lined the four-lane road behind the clinic. Â

The road intersects with the main street of the once prosperous steel town. Small bright flowers decorate its grassy median strip. More than half of the real estate flanking it appears to be unoccupied. Â

Back at the clinic, work at the front desk had eased. This was a slow day, with no surgeries scheduled, a staffer told me. The next day, when Sarah returned, would be busier. Protesters would likely show up.Â

Sarah emerged from an office in the back. She reminded the front desk staff she hadn’t paid her share for the abortion. She retrieved her wallet from the front pocket of her knapsack and counted off $600.Â

How does Sarah tell if the cramping is severe?

Regional Logistics Center sent an Uber to take us to a national chain hotel on a stretch of highway lined by fast-foot and hotel chains.Â

The check-in clerk frowned at Sarah’s ID.Â

“Are you with her?” she asked me. “She can’t stay here without an adult.”Â

Sarah was old enough to make her own medical decisions and old enough to vote, but she had to be at least 21 to stay at this hotel, unless someone at least 21 was traveling with her, whether staying in the same room or not.Â

“And they know that,” the clerk said with clear resentment, referring to Regional Logistics Center, although it was not clear what anyone had done wrong.Â

If Sarah had gone alone, a Regional Logistics staff member told me later, the agency that booked her would have instructed the hotel not to require identification.Â

We dropped our bags in our rooms and headed to McDonald’s. Â

During the appointment earlier, the doctor had given her an injection to prepare her uterus for the abortion. On the next day, a doctor would insert slender rods into her cervix to dilate the opening to her uterus. The rods, made of a natural fiber, would absorb moisture and continue to expand after she returned to the hotel. On the third day, her abortion would be completed.Â

The prospect of returning to a hotel room where she would be alone after undergoing the second day procedure weighed on her. The nurse had given her instructions that included an emergency phone number if she had severe cramping. She had never had cramps with her periods, so she wasn’t sure she would know if any cramps were severe.Â

She was weary and anxious. We said goodnight to each other about 5 p.m. and retreated to our rooms.Â

She called about 10:30, to ask if I was coming with her the next day, her voice so soft she sounded almost like a child. She reminded me that we would be there in 12 hours.Â

‘The birthrate is below replacement’Â

Waiting to clear the clinic’s security the next morning, Sarah had her back to the man who was calling her a murderer. She thought he had a bullhorn, she said later.Â

He didn’t. He was shouting at the top of his lungs from about 60 feet away.Â

Protesters can’t enter the parking lot, but they can stand on the sidewalk surrounding three sides of it. This man was facing the door where patients enter the building.Â

Five or six volunteers stood inside the parking lot wearing rainbow patterned vests that identified them as patient allies — clinic escorts. They carried rainbow patterned golf umbrellas to block patients’ view of protesters and of the gruesome pictures some waved, depicting mutilated babies. Â

We were early for Sarah’s second-day appointment.Â

Still, as soon as Sarah checked in, a nurse led her inside. No sound from outside penetrated the clinic walls.Â

I went back outside.Â

On the sidewalk to the left of the parking lot, a woman held a stack of pink plastic sandwich-size baggies and offered me one with a dollar bill stapled to a business card on top. Â

“U.S. birthrate is below replacement since 2007,” she said. “It’s called genocide. We’re killing our own race. We’re killing our own national people.”Â

“Replacement” refers to the rate of births meeting or exceeding the rate of deaths. It was the responsibility of the women and girls entering the center, she was arguing, to bear children to replace people who die.Â

The baggie held business cards for crisis pregnancy centers, charities, 12-step programs and social service agencies, a thumbnail-size tin medallion depicting the Virgin Mary, a card inscribed with prayers, and two chocolate chip cookies.Â

“That should tide her over for the next 18 years!” a clinic staffer said, looking at the bag later.Â

Sarah came out after two hours.Â

“They gave me medicine that made me a little loopy, frankly,” she said, sounding grateful. They also had reassured her that the risks of any complications were low. Â

She was ready to turn in. I wasn’t sure she had slept much the night before or eaten that day. She was to have no food that night. Her next and final appointment, which could require sedation, was set for 8:30 the next morning.Â

Abortion opponents yell: ‘Mommy, don’t kill me’Â

We arrived at Hope Clinic at 8 a.m. A couple of patients were lined up before Sarah, waiting for the clinic to open. Â

Once she checked in to the clinic, Sarah hoped she would receive her flight information for the next day’s trip home. Â

The volunteers who shield patients from protesters arrived next.Â

While we waited for security to admit patients, a van pulled up and parked on the street parallel to the clinic parking lot. Lettering on its lime green and purple sides labeled the van “Small Victories Mobile Medical Unit” and said “Free Ultrasounds.” A woman wearing purple scrubs and stethoscope hanging around her neck had planted herself by the back of the van.Â

It is not a medical unit, clinic staff said later. It is there to divert women away from medical care and to places offering diapers, child car seats and contacts with adoption agencies in the hopes that those offerings will persuade women to continue pregnancies they had come to the clinic to terminate.Â

A few more protesters arrived, and a stream of calls from across the parking lot began: “Mommy don’t kill me.” Â

The security guard opened the door and let the first patients in.Â

A man arrived next and took position near the driveway into the parking lot. Scowling, he held his sign: “DO NOT MURDER YOUR BABY.”Â

On the other side of the driveway a lanky white-haired man waited with a pleasant, cheerful and welcoming smile, waving at the patients as they arrived. He resembled Mr. Rogers, of children’s television fame, but instead of a cardigan he wore a light blue vest, labeling him a “volunteer.”Â

Whatever he was volunteering for, he remained on the sidewalk off the grounds and so was not there at the invitation of the clinic.Â

Sarah passed through security. A nurse met her downstairs.Â

I went back outside to ask the man with the friendly smile if he would talk to me.Â

A snarl that felt like hate replaced his smile.Â

He spoke to me through bared, clenched teeth.Â

“You want to make me look like some kind of a case,” he said.Â

The woman with the pink plastic baggies was in the same spot as the day before.Â

“Any woman who has a baby,” she told me as I passed, “cells from that baby stay in her body forever.”Â

I went back inside, where Sarah had given staff permission to talk about her care.Â

The procedure itself wouldn’t take long but they would give her medicine first to soften the opening to her uterus and wait for it to work before they began. They would monitor her after the procedure before releasing her, longer than they otherwise would because she planned to travel the next day.Â

A father came in with his teenage daughter. A woman came in with two young children and a friend. When the woman went inside, the friend retreated to the clinic’s family room, filled with toys and games. A couple came in.Â

The waiting room television was tuned, as it had been the preceding two days, to a game show channel. Match Game shows from the 1980s filled the afternoon.Â

Abortions at an earlier stage than Sarah’s take place in one visit, in less than 45 minutes followed by an hour or less in recovery. Patients came and left.Â

It was close to 3 p.m. when Sarah texted: “Hi I’m done with my surgery I am resting right now and they will be monitoring me for two hours I believe.”Â

It was after 6 p.m. when the clinic medical director came out to talk.Â

Sarah was running a low fever. It may have been a side effect of the medicine they had given her before the procedure, but it also could be a sign of infection. The vagina is home to bacteria that can cause infection by gaining entry to the uterus through a dilated cervix. Â Â

The doctor had arranged to transfer Sarah to the hospital back over the state line in St. Louis for the night to make sure if she had an infection it would be treated. She excused herself to call her colleagues at the hospital so they would be prepared to meet Sarah.Â

‘Where is her family?’Â

Sarah was sleeping, hooked up to an IV bag the next morning. The hospital had taken six hours the night before to move her to a room.Â

She woke up when I came in. She needed one more infusion of antibiotics before she left, according to the nurse, Sarah told me. Then, Sarah hoped, we could still catch a plane back to Florida. Â

“I want to go home,” she said.Â

Sarah gave me the key to her hotel room, and I went back to Granite City to retrieve her things.Â

Her bag was already packed. Â

The hotel manager, who hearing she was in the hospital had given us an extra half hour to check out, had a question.Â

“I know why she’s here,” he said. “Why isn’t her family with her?”Â

Her family members all had jobs. Four days off would be a hardship.Â

“Yes, jobs are one thing,” he said. “But family should be here.”Â

He added he thinks having an abortion is wrong. Â

“They should do a better job of teaching about contraception in schools,” he conceded.Â

Florida’s law, and those in surrounding states that lead patients to Granite City, he added, however, “has been good for business.”Â

This hotel alone gets about 25 guests a week who are in town to end their pregnancies, he said. Â

It is one of several in the area that the Regional Logistics Center uses regularly.Â

‘Am I cured?’

Back at the hospital Sarah slept. A nurse came in to remove Sarah’s IV at 1 p.m. and told her she was free to go.Â

“Am I cured?” Sarah asked. (Yes, if she took all her antibiotics).Â

“Could you take my temperature one more time?”Â

It was normal, but she could stay until we needed to go the airport.Â

Sarah collapsed back into the bed.Â

We left the hospital at 4. Sarah did not want to take a chance of anything happening that could keep us from catching our flight at 7 p.m.Â

Our plane, the only nonstop that day, as it turned out, was delayed three hours.Â

It was 2 a.m. Friday when the taxi pulled up in front of her home.Â

It had been four days since she had left before dawn.Â

I asked her if everything would be all right with her family. She had been texting through the day.Â

She smiled.Â

“They just want me to be OK.”

Antigone Barton is a reporter with The Palm Beach Post. You can reach her at [email protected]. Help support our work: Subscribe today.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=6711d986e7c7488a9e1d2659f4e073b4&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.azcentral.com%2Fstory%2Fnews%2Flocal%2F2024%2F10%2F17%2Fflorida-abortion-ban-sends-young-woman-on-trek-halfway-across-america%2F74940482007%2F&c=17304315635652827613&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-10-17 16:31:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.