5 things to know about semiconductors and Arizona

Since the passage of the CHIPS and Science Act in 2022 Arizona has assumed a role of growing significance in the semiconductor industry.

Arizona has emerged as the nation’s hot spot for semiconductors, with more than $100 billion in recent corporate investment announcements around metro Phoenix. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. and Intel Corp. lead the way, with dozens of suppliers setting up shop in the region.

But it wasn’t always this way. For decades, agriculture and mining dominated, and more recently real estate, tourism and other service industries flourished.

The young state played catch-up for decades to claim its niche. A world war and the threat of another brought defense contractors to the state. That laid the foundation for semiconductor businesses to follow.

This is how Arizona got where it is in the semiconductor industry.

1941: World War II and Luke Air Force Base

For the first few decades after gaining statehood in 1912, Arizona’s economy was defined by “The Five C’s:” citrus crops, cotton production, cattle raising, copper mining and the dry, warm climate that attracted snow-weary newcomers from colder parts of the nation.

That started to change before and during America’s involvement in World War II. Defense strategists in Washington, D.C., worried about German and Japanese attacks. Much of the nation’s industrial might and population was concentrated on the coasts.

Arizona’s population in 1940 stood at around 500,000 people, or less than 7% of that of New York City at the time.

The government convinced military contractors to disperse their factories and move some inland.

Arizona became one such destination, attracting investments from businesses including Goodyear Aircraft Corp. (which decades later was absorbed into Lockheed Martin), Air Research Manufacturing (later Honeywell) and aluminum giant Alcoa. The military in 1941 established an airfield in the West Valley, which became Luke Air Force Base. It grew to become the Air Force’s largest fighter training facility during World War II.

After the war, the government mothballed Luke, but the Korean War and escalating Cold War tensions forced a rethink. In 1951, President Harry Truman renewed the policy of industrial dispersion and reactivated Luke. Manufacturing clusters grew around it and airports in metro Phoenix, Tucson and Yuma.

“Arizona always has had a lot of high tech around aerospace and defense,” said Michael Kozicki, a professor in Arizona State University’s school of electrical, computer and energy engineering.

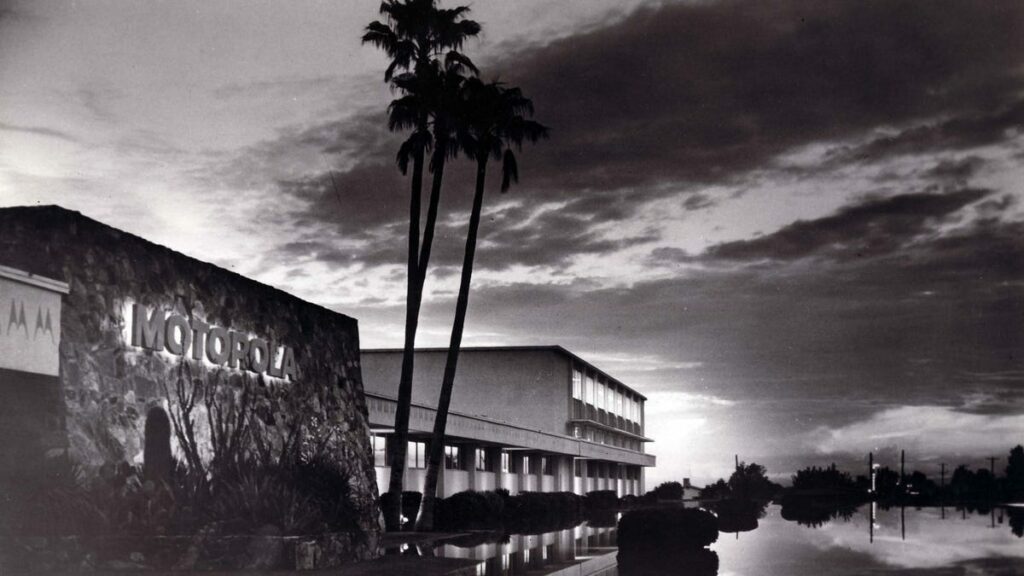

1949: Motorola brings factory to Phoenix

Semiconductors, invented in 1939, started to come into commercial production by the 1950s, and Arizona policymakers moved to lay the foundation for the industry’s growth.

The Greater Phoenix Economic Council, in a 2010 documentary, attributed much of the state’s success in wooing tech companies to Gov. Paul Fannin, a former businessman who led the state from 1959 to 1965.

He pushed through legislation to lower corporate taxes and transition Arizona into a right-to-work state, and he encouraged visits by corporate executives from other parts of the country.

Motorola was one critical early invitee that put down roots, and Arizona got a break in an unlikely way. Doctors urged Dr. Daniel Noble, a key engineer and executive at the company, to leave cold, damp Chicago for the dry, warm climate here. He did and fell in love with the desert lifestyle.

“They basically built a fab for him,” said G. Dan Hutcheson, an industry analyst at TechInsights, referring to a factory Motorola developed at McDowell Road and 52nd Street in Phoenix, with operations commencing around 1956.

But that wasn’t the only impetus.

“When Motorola was looking to expand and expand quickly, they came to Arizona, and what the leaders here offered was, the most important thing they could offer, which was cooperation and collaboration,” said George Weisz, son of former Motorola CEO Bill Weisz, in the GPEC documentary.

Motorola, a company whose origins were in batteries, radios and walkie-talkies, had a research laboratory up and running in the 1950s in Phoenix. It morphed into a semiconductor division.

Arizona’s population surpassed 1 million by 1956, providing a ready workforce for these and other new businesses.

“Motorola was the entity that really sparked the growth,” Kozicki said.

1958: Arizona State becomes a university

Statewide voters cooperated in 1958 by approving a change in the status of the Arizona State College to Arizona State University. The same year, ASU established an engineering school, opening the talent pipeline the tech companies needed.

Throughout the 1960s, the school graduated 25 engineers.

1960s and 1970s: Arizona’s tech sector expands

The semiconductor industry ballooned during the 1960s and 1970s.

Work on military and aeronautical programs also continued during this period. Goodyear Aircraft Co. developed an advanced radar system used in American spy planes during the 1960s, for instance.

Don Beckerleg was on a team tasked with building the best radar in a relatively short period of one year.

“Here’s a big bag of money,” an Air Force officer told the company, Beckerleg recalled in the GPEC documentary. “If you need more, let us know.”

By 1965, according to GPEC, more than 700 manufacturers were operating around the Phoenix metro area, roughly 200 of them added during Fannin’s time as governor.

One of the newcomers, after Fannin left office, was ASM International. The Dutch maker of complex, expensive manufacturing equipment moved its North American headquarters to the Valley in 1976.

By then, Arizona’s population had swelled beyond 2.3 million and ASU was graduating around 18 engineers a year.

1980: Intel Corp. opens in Chandler

The 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s saw some more gains for Arizona in the semiconductor field.

ASU renewed its focus on engineering excellence in the 1980s and boosted the university’s status in the field, Kozicki said. That mattered to the tech giants.

When researching locations for possible expansion, semiconductor companies almost always seek a nearby university with an engineering school that’s “up to snuff,” Hutcheson said.

By 1985, ASU’s engineering school was turning out around 960 graduates a year. Almost 3.2 million people now lived in Arizona. And the industry poured in.

Arizona became the home of factories for Intel Corp., which began operations in Chandler in 1980 and now counts the largest workforce of any type of manufacturer operating in Arizona, according to this year’s Republic 100 special report.

The semiconductor facilities operated by Motorola and others begat more expansions. Intel, for example, came here thanks to the presence of Motorola, which at the time was still making advanced semiconductors, Kozicki said.

Amkor Technology, a company with South Korean roots that packages semiconductors into end products, established a metro Phoenix presence in 1984.

Chandler-based Microchip Technology sprang up and is today worth about $41 billion. It was spun off from another semiconductor maker, General Instrument, in 1987.

NXP Semiconductors, another company from the Netherlands, has operated factories or fabs in Chandler since the 1990s.

The industry is so specialized, with so much expensive equipment and unique infrastructure, that chipmaking companies tend to cluster near others. They also bring in suppliers.

“You can’t just go out and get Fred’s moving company to bring in the equipment or Jack’s lawnmower repair to change the oil,” Kozicki said. “There are only a handful of regions in the world that can handle this (specialization), and Phoenix has had that for decades.”

1990s to 2020: The offshoring of tech manufacturing

But by this time, Asian chipmaking competitors were also on the upswing.

U.S. companies continued to flourish in many areas, such as in designing semiconductors used in a wider array of electronic products. But much of the advanced manufacturing was going overseas.

In particular, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. started from scratch back in 1987, after buying dated technology from RCA.

TSMC grew quickly as orders poured in. Roughly a dozen years after its founding, TSMC was earning almost $1 billion in profits on $3 billion in revenue, and those numbers have continued to climb.

These developments were embraced in the United States.

The subsequent concentration of advanced chip manufacturing in Taiwan, South Korea and elsewhere wasn’t an accident but instead resulted from a series of “deliberate decisions” by U.S. government officials and corporate executives, said Chris Miller, a Tufts University professor and author of “Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology.”

American corporate executives, he said, liked cheap labor in East Asia while “Washington’s foreign-policy strategists embraced complex semiconductor supply chains as a tool to bind Asia to an American-led world.”

It also bound America to an Asian-led industry.

By 1995, when the digital revolution was in full swing, more than 4.1 million people called Arizona home, and its top engineering school sent out more than 1,100 graduates.

From the late 1940s through the 1970s, “We were this tech giant,” said Christine Mackay, community and economic development officer for Phoenix, referring to Arizona’s roots in the field.

“But by the early 2000s, we had lost our way,” she said.

2004: Motorola backs out of semiconductors, splits up and sells

Hutcheson agrees that many American tech companies welcomed the Asian chipmaking trend as the cost of building factories was escalating, along with other expenses.

“Big U.S. companies bought into TSMC’s rise,” he said. “A lot of companies, like Motorola, were asking, ‘Why are we making our own chips when we can to go to Taiwan and make them cheaper?’ “

In 2001, Arizona employed more than 33,500 people in the semiconductor industry and related fields, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data. Earlier data is not readily available, but that year represented the high-water mark in the past quarter-century.

The rapid expansion of ASU’s engineering school had tapered off a little but still generated more than 1,200 graduates that year. Meantime, Arizona’s population continued to swell. It stood at almost 5.3 million.

Hutcheson, who now lives in California, said his father was a physicist for about three years at Motorola’s plant on McDowell Road and 52nd Street. The semiconductor analyst said he once chatted with Christopher Galvin, the son of Motorola founder Bob Galvin, and sensed the company eventually would dispose of these operations.

“Christopher Galvin didn’t like semiconductors, so he choked it off,” Hutcheson said.

The technology was evolving so fast that it was costly for many companies to keep pace, Hutcheson added. Due to rapid obsolescence, “Your product portfolio could die on you.”

Galvin served as Motorola’s chairman and CEO from 1997 to 2004. In 1999, the company spun off its semiconductor components group to form On Semiconductor, a thriving chip manufacturer headquartered in Scottsdale. Onsemi, as the company now calls itself, is one of the largest Arizona-based corporations, with a stock market capitalization worth of $30 billion.

Motorola spun off its semiconductor products division in 2004 to form Freescale Semiconductor, headquartered in Austin, Texas. This company in 2015 merged with Dutch chipmaker NXP, with operations in Chandler.

Motorola split further, with Motorola Mobility, now part of Lenovo, focusing on cellphones and cable-television equipment and Motorola Solutions dedicated to other communication products and services. Iridium Communications, a satellite communications company with operations in Tempe, also was once part of Motorola.

Motorola’s presence in Arizona brought an unwanted legacy, too. The Environmental Protection Agency and the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality have declared the site of the former 52nd Street fab a Superfund site. Cleanup of polluted groundwater below the facility, which began in the 1980s, continues.

2020: The pandemic forces a change

In recent years, enthusiasm has dimmed for long, complicated semiconductor supply chains that stretch across the Pacific Ocean and, sometimes, across the Atlantic to Europe.

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed a vulnerability, paralyzing shipments of some products. In addition, China’s continuing threats against Taiwan raised fears that an invasion or blockade of the island nation could disrupt the global trade in semiconductors.

In 2019, the year before the pandemic reached Arizona, the state’s population had ballooned again to almost 7.3 million. ASU, too, was rapidly expanding its engineering program, cranking out more than 3,800 graduates that year. And semiconductor industry jobs were bouncing back after reaching the century’s low point two years earlier. By 2019, more than 19,000 worked in the field in Arizona.

These factors worked in Arizona’s favor when TSMC announced in 2020 that it would build an advanced chipmaking plant in northwest Phoenix for $12 billion. TSMC deepened the commitment to $65 billion in 2024, with commercial production months away.

TSMC has preliminarily qualified for $6.6 billion in funding under the federal CHIPS and Science Act, and Intel is in line for even more, $8.5 billion for its Chandler complex and those in other states. With these and other developments, Arizona also has attracted a slew of semiconductor suppliers, and the state has benefited in other ways, such as with the establishment of a research “hub” focused at ASU, also with CHIPS Act funding.

Since May 2020, when TSMC declared that it would build a new factory or fab in north Phoenix, Arizona has snagged 20 of 90 new semiconductor investment or expansion announcements across the nation, according to an August update by the Semiconductor Industry Association. Texas, in second place, has 10 new projects.

The new Arizona investments run the gamut from research and development to chip manufacturing, along with material suppliers, equipment makers and the end-stage packaging of chips. Among the biggest: A $2 billion testing and packaging investment by Amkor Technology in Peoria.

At last count, 22,000 people worked in the microchip field in 2023. ASU graduated more than 5,700 engineers, and a new wave of migration brought Arizona’s population to 7.4 million, with 180 people arriving every day, on average.

The Arizona Commerce Authority reported it was trying to attract 45 “mega projects” representing at least a $500 million investment each.

Since the CHIPS Act, the state has added 40 semiconductor-affiliated companies that have expanded or set up shop, representing more than 16,000 new jobs and $102 billion in investments, according to the Arizona Commerce Authority.

Arizona now plays a leading role in the global microchip industry, after eight decades of investment and preparation.

“Arizona has always had its act together on these things,” Hutcheson said.

Reach the reporter at russ.wiles@arizonarepublic.com.

This is one of a series of articles about Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. and the growth of the semiconductor industry in Arizona. Read more on azcentral.com.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66fc19b9d66040ec9617b80fdfb9e14f&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.azcentral.com%2Fstory%2Fmoney%2Fbusiness%2Ftech%2F2024%2F10%2F01%2Ffrom-motorola-to-tsmc-arizona-built-on-its-technology-base%2F75369361007%2F&c=9075215276076676893&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-10-01 02:13:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.