This issue is arguably more pressing than ever. President Trump just pardoned a man whose aggressive interior enforcement immigration regime illegally persecuted Arizona’s Latino community, with Americans living in border communities such as Arivaca particularly hard hit by the sort of policies Joe Arpaio promoted and Trump just effectively endorsed.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

SUBSCRIBE & SAVE

Sign up for The Week’s Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And if President Trump gets his way, things will get immeasurably worse.

Arivaca is nestled in the Altar Valley in the foothills of the San Luis Mountains, in what the ACLU has dubbed the 100-mile Constitution-free zone. This is the area along the border and coastal U.S. where, thanks to some dubious court rulings, immigration authorities have acquired almost the same powers to stop and search people and property without warrants that they have at ports of entry. Nearly two-thirds of all Americans live in this zone, although immigration authorities aren’t doing much in the northern half bordering Canada. But post 9/11, the Southwest corridor where Arivaca, along with dozens of other Arizona border towns, sits, became Ground Zero in Uncle Sam’s fight against unauthorized immigration and drug smuggling from Mexico.

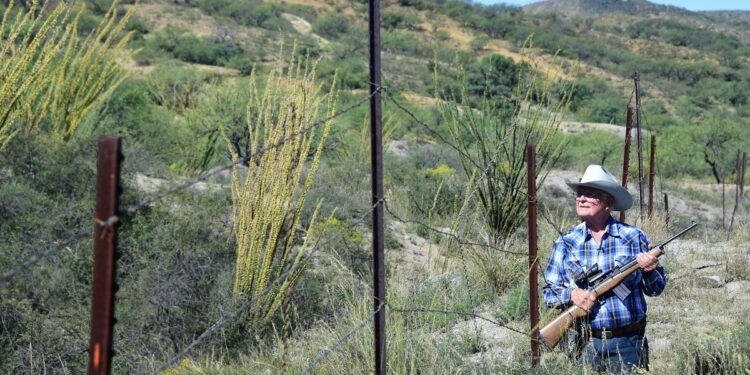

Customs and Border Patrol, a federal agency in the Department of Homeland Security, installed ugly surveillance towers with swiveling cameras atop lovely hills to scan for anyone scurrying in the surrounding ravines and slopes around the town. It laid underground sensors to track suspicious movements. It let roving Border Patrol units constantly zip through town in their heavy-duty all-terrain vehicles searching for migrants, causing occasional accidents and cratering roads that the county does not have the funds — and Border Patrol claims it does not have the authority — to fix. It made the sprawling private yards of ranchers fair game for armed agents with dogs to snoop around any time without homeowners’ permission — or a court order — looking for holed-up Mexicans.

But worst of all are the checkpoints that Border Patrol planted outside the town, making it impossible for anyone to leave or enter without being stopped. These were supposed to be “temporary” measures until the border was brought under control. That was 10 years ago. Now they’ve become enduring symbols of the iron fist of government.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

None of the Arivaca residents I talked to could remember a single instance when the checkpoints had actually thwarted a big drug heist or apprehended a large truckload of unauthorized immigrants. This is partly because Arivaca is a very safe, even sleepy, town that isn’t a major thoroughfare for such activities. And it is partly because to maintain their “temporary” designation and avoid running afoul of the law barring permanent interior checkpoints, Border Patrol occasionally shuts the checkpoints down for “inclement weather.” At that point, hilariously, border jumpers watching from nearby hills or ranches make a break for it.

Arivaca residents, however, don’t have the luxury to coordinate their movements with checkpoint timings. The town has no school or hospital and only one tiny grocery store and a little cafĂ©. So most people end up making frequent out-of-town trips for routine errands. Yet every time they leave, they feel like they are going from the occupied West Bank to Israel. “It is hard to believe that this is the United States of America,” fumes Leesa Jacobson, a local activist. Most people try and minimize out-of-town trips to avoid encounters with checkpoint agents.

In theory, agents are not supposed to ask anyone anything beyond whether they are an American citizen. If the person answers “yes,” he or she is supposed to be waved through without any further questions — unless there are some genuine grounds for “reasonable suspicion.” But border officers routinely drive a patrol truck through this loophole.

Practically anything can raise their suspicion. Being Hispanic is definitely a trigger point. Jacobson’s outfit, People Helping People, set up a makeshift monitoring station across from the checkpoint for a few months (before Border Patrol pushed them to an unobservable distance). During that period it found that Latinos, who constitute about 20 percent of Arivaca’s population, some of whom have lived there for multiple generations, are 26 times more likely than whites to be asked to show identification and 20 times more likely to have their vehicle inspected. Indeed, so rampant is the racial profiling, says Jay Rivett, an Ohio retiree settled in Arivaca, that his daughter, who is married to a Hispanic man and lives a few hours away, no longer likes to visit him for fear of harassment. “We visit her now,” Rivett laments.

White people, too, are hardly immune to governmental abuse. If they are driving a sedan with a closed trunk rather than an open pick-up truck, that can raise “reasonable suspicion.” If their truck has camping gear or heavy equipment, that can raise “reasonable suspicion.” It they are in a hurry and don’t make requisite small talk with checkpoint agents, that can raise “reasonable suspicion.” If they are too mouthy, that can raise “reasonable suspicion.”

But the worst treatment is reserved for those who dare to assert their rights and refuse to pop their trunk without the agent giving them a legitimate reason. In that event, they are sometimes asked to wait in their car until a canine unit can come and sniff their car, a process that can take hours. Essentially, the choice for locals is to submit to unconstitutional inspections or waste time and face harassment.

Thanks to the checkpoint, Arivaca residents don’t even have to explain when they are late for appointments. “People just understand if you are from Arivaca,” winced Leslie Rivett, Jay’s wife.

What is the need to treat this community, which consists of 75 percent retirees, a good chunk of whom are former cops, this way? Basically, Jacobson notes, the feds have designated the whole area as suspicious. Hence, as far as Border Patrol is concerned, you never know when one of the locals will start making drug runs for cartels or stuffing illegal immigrants in their trunks for coyotes. So they are all basically considered guilty until proven otherwise.

Arivaca residents have complained to the regional Border Patrol office to no effect. Better supervision from the top could certainly make individual field agents behave a bit better. But the fundamental problem is with interior enforcement itself. That’s because given America’s diverse population, there are no external proxies that can accurately distinguish legal from illegal, citizen from non-citizen. Border agents need broad latitude to ignore constitutional protections to make such distinctions, which inevitably affects everyone. “We don’t fear the illegals,” Jay Rivett seethes. “We fear armed Border Patrol agents.” And if Trump doubles down on his plans for more aggressive interior enforcement, such checkpoints, about 100 at the last counting, about 11 in Arizona alone, Jacobson believes, will proliferate in even more parts of the 100-mile Constitution-free zone.

So what’s the alternative?

Arivaca residents despise the idea of a giant wall — “beautiful” or not — defiling their gentle highlands and rolling meadows. They don’t even think it would be physically possible to erect such a structure given the topography of their countryside. But they do want all border control functions to actually happen at the border. Rob Daniels, a spokesperson for the Arizona Customs and Border Patrol, issued a statement insisting that such checkpoints are part of a “layered enforcement” strategy to border security. (He wouldn’t comment beyond that because of “pending litigation.”) But Arivaca residents vehemently disagree with that approach. They are convinced that if Trump combined the money he wants to spend on the wall with all the existing spending on interior enforcement, he could put manned stations close enough on the Southern border to create a relatively impenetrable barrier. It might be overkill, but it’s better than a physical structure, as far as they are concerned.

In addition, they believe that the problem will never be fully solved without more official avenues for migrant workers to legally work in the United States. “All they want to do is make a living,” a retired construction worker who didn’t want to be named said. He suggested creating visa-processing units at ports of entry where anyone who wants a visa could get one by posting the usual fees and a $1,500 bond that would be escrowed and handed back to them when they return. “They pay more than that to coyotes anyway,” he pointed out — and it’ll give them an incentive not to overstay.

Such a system would separate out the economic migrants who’d rather come to America legally from the truly bad immigrants who’d rather not, diminishing the number of illegal border crossing to a more reasonable level.

This is eminently sensible advice not from Beltway elites or D.C. think tanks for whom Trump has contempt — but from the real experiences of real Americans whom he says he respects. He should listen to them.

How about it Mr. President?

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=67592129961a4f2bbec81a9bd11e7ffa&url=https%3A%2F%2Ftheweek.com%2Farticles%2F719688%2Fhow-america-turned-arizona-border-town-into-police-state&c=1315702602099981560&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2017-08-27 13:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.