5 things to know about semiconductors and Arizona

Since the passage of the CHIPS and Science Act in 2022 Arizona has assumed a role of growing significance in the semiconductor industry.

In north Phoenix, a factory is being born. Ringed by mountains and a bald expanse of Arizona desert, red and yellow cranes cast spindly shadows over the cubic skeletons of what will become multistory buildings. The campus, when completed, will span hundreds of football fields.

The factory is big news for metro Phoenix. It will bring thousands of jobs. Itﻗs expected to be a watershed in housing, development, and high-tech expansion. Itﻗs part of a manufacturing boom sweeping the country in the wake of large federal investments.

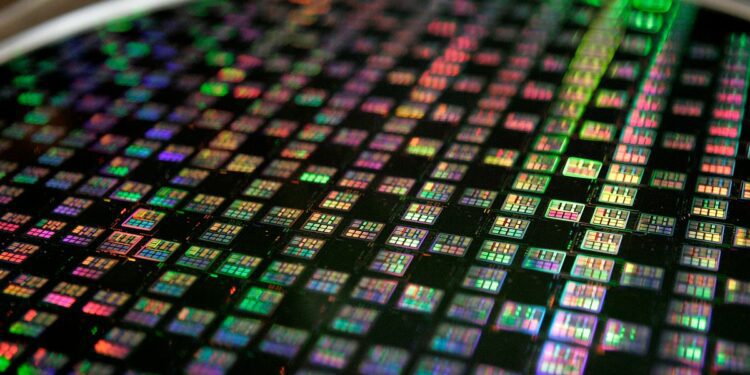

But in the halls of Congress, the White House, and the Pentagon, itﻗs also known for a different reason. The Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. will make semiconductors, known as ﻗchips,ﻗ the silicon morsels present in virtually all electronics. In the age of computers and artificial intelligence, they have become a linchpin of the global economy.

The success of the factory, and others like it, is seen as vital to national security, and one of the existential imperatives that will help maintain the U.S.ﻗ dominance on the world stage.

ﻗYou can’t have a strong economy, or a strong defense, without semiconductors,ﻗ Arizona State University supply chain professor Dale Rogers said. ﻗAnd we are in the center of the universe for semiconductors, right here in the Phoenix area.ﻗ

Facing heightened competition from China, and growing demand for electronics, reviving Americaﻗs chip industry has in recent years been widely recognized as an urgent priority.

Factories like TSMCﻗs are making Phoenix a nucleus for the building blocks of the countryﻗs economic and military might.

That has brought an unusual amount of attention to what are ordinarily local minutiae of getting a factory off the ground. Concerns like environmental reviews, labor agreements, and staffing shortages have garnered attention from the highest levels in D.C.

The projects, in short, are too important to fail.

Great power competition puts Phoenix on the map

While the Sonoran Desert slept, a message flashed across cellphones halfway around the world: “Incoming missile/rocket threat.”

“Seek immediate shelter.”

Sirens blared and vehicles and people left the streets of Hsinchu, Taiwan as part of a drill against missiles being fired from China.

Phoenix’s semiconductor industry is part of the same globe-spanning geopolitical drama, according to Sujai Shivakumar, a senior fellow with the D.C.-based think tank Center for Strategic and International Studies.

It starts with competition between the great powers. For decades, free trade policies allowed Americaﻗs manufacturers to move abroad in search of cheaper labor and more favorable markets. Western powers welcomed emerging economies, like Chinaﻗs, into global trade institutions, in hopes that the country would become an ally as it integrated into the global economy.

ﻗThere was a consensus that things are geopolitically calm, that China is not our rival. It doesnﻗt matter where things are produced as long as you have efficient value chains that can span the globe,ﻗ Shivakumar said. ﻗThat led to wholesale offshoring of our industry.ﻗ

Several factors changed that view, Shivakumar said. Chiefly, China is now seen as a strategic rival. Its rapid rise as a manufacturing power has allowed it to outcompete America and its allies in global markets.

Over time, American strategists have gone from rooting for Chinaﻗs economic success to worrying about it.

Those concerns came to a head during the COVID-19 pandemic, when supply chain disruptions created new fears that the now-outsourced manufacturing supply chains could be a vulnerability for the U.S.

Chips were chief among those concerns. The neurons inside the worldﻗs ﻗsmartﻗ electronics, chips are unthinkably small ﻗ measured on a scale 1 million times smaller than the increments shown on a ruler ﻗ and yet theyﻗre a master variable of the global economy. The growth of artificial intelligence has made chips omnipresent in computers, cars, smartphones, medical and military equipment and more.

Theyﻗre vital to the most advanced weapons that the U.S. military uses to fight wars. Chips are the brain inside of missiles that can chase their targets, communication devices that allow for coordination around the globe, and satellites that transmit intelligence back home.

ﻗHeavy weapons arenﻗt nearly as effective as smart weapons,ﻗ said Rogers, whose ASU chair is sponsored by the chip company onsemi.

Add to the mix that Taiwan, the island roughly 100 miles off Chinaﻗs southeast coast which produces the lionﻗs share of the worldﻗs advanced semiconductors, is facing a military threat of its own.

Itﻗs seen as vulnerable to an invasion from China.

Strategists disagree on if and when China might make that move. But Taiwan, and its allies in the Pacific, are seen as likely to be the first front if conflict between the U.S. and China turns hot.

Itﻗs enough to make American strategists nervous.

ﻗA lot of the chip manufacturing is located along the Pacific ﻗRim of Fire,ﻗﻗ Shivakumar said. ﻗItﻗs too much concentrated in one very vulnerable location.ﻗ

U.S. Sen. Mark Kelly, a veteran who sits on the Senate’s Armed Services Committee, is a leading voice on the issue.

The Arizona Democrat was a chief negotiator of the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act, a massive piece of legislation designed to lure American semiconductor manufacturing with promises of hefty tax benefits, multibillion-dollar grants or loans to help get factories off the ground, and billions of dollars more for research and development.

He has echoed the idea that the factories will reduce the country’s reliance on supply chains overseas.

“Our economy now, I think it’s fair to say, runs on semiconductor chips. We can’t risk losing access to them,” he told The Arizona Republic earlier this year.

Arizona: A ‘second island’ for chip manufacturing?

With Taiwan under threat, Arizona is seen as a ﻗsecond islandﻗ where chip manufacturing can take root.

That originally happened more for economic reasons than geostrategic ones. Arizona was among the hardest hit by the 2008 Great Recession, recalled Danny Seiden, president and CEO of Arizonaﻗs Chamber of Commerce. State leaders were looking for ways to boost the economy aside from housing and real estate development and its famous alliterative selling points: copper, cattle, cotton, citrus and climate.

ﻗWe were saying, ﻗhow can we diversify our economy?ﻗﻗ Seiden said. ﻗWhat is it that Arizona has to offer, outside of the typical 5 Cﻗs that you always hear about?ﻗ

ﻗWe realized we could be a manufacturing base.ﻗ

Several state leaders helped oversee that change, he said, including former Republican governors Jan Brewer and Doug Ducey and former Arizona House Speaker Kirk Adams. The Arizona Commerce Authority, then a newly formed public-private partnership, played a role in attracting capital, too.

In fairness, Rogers said, Arizona was an ﻗeasyﻗ sell.

The state had one of the most reliable power grids in the country. It wasnﻗt as expensive as neighboring California, where many tech companies are headquartered. Arizonaﻗs Republican-led leadership enticed businesses with tax breaks that made it more hospitable to manufacturers compared with some of its Democratic-run neighbors.

The stateﻗs workforce was attractive, too: Arizona State University provided a trove of faculty and scientists to give businesses cutting-edge intelligence.

Counterintuitively, Rogers added, ﻗas crazy as this is ﻗ۵ the cheapest water of any American city is in Phoenix.ﻗ

And so, one by one, Arizona ended up with several anchors of the supply chain critical to the United Statesﻗ economic and military standing. TSMC announced plans to build three factories in Phoenix, manufacturing high-end chips for customers including the tech giants Nvidia and Apple.

Scottsdale-based onsemi, a tech company formerly known as On Semiconductor, makes the ﻗlittle chipsﻗ needed to supplement smartphones and other devices, Rogers said. Intel is breaking ground in Chandler to produce leading-edge semiconductors that aren’t currently made in the U.S.

Arizona State University, the largest public university in the country, is playing a central role too. Itﻗs helping U.S. manufacturers match the pace of Chinese innovation and keep up with an observation known as Mooreﻗs Law, which holds that the number of transistors on microchips has doubled roughly every two years.

ﻗThere is a technology and R&D race going on as well,ﻗ Shivakumar said. ﻗSo itﻗs really important that research organizations like ASU ﻗ۵ help to maintain the momentum and comparative advantage.ﻗ

The year 2022 brought another watershed moment with the passage of the CHIPS and Science Act.

Arizona competed for those dollars, and it succeeded.

The state has seen some of the biggest private investments in state history, a host of workforce accelerators for the chips industry, and Arizona universities have attracted hundreds of millions of dollars in grants.

National security goals hinge on local Arizona issues

Ordinarily, the nuts and bolts of standing up a factory ﻗ negotiations over labor conditions, the environmental reviews, and finding and training workers ﻗ are dealt with on a case-by-case basis or at the local level.

But the stakes of Arizonaﻗs projects have brought new attention, sometimes from the highest levels of the federal government. It has signaled it will move heaven and earth to develop the staff necessary to build and sustain the semiconductor industry ﻗ putting massive sums of money into workforce development and training. And Biden recently signed into law a proposal to exempt semiconductor projects from certain environmental permitting requirements.

Kelly, who sponsored the permitting bill, praised it as “smart, effective policy that will maximize our efforts to bring microchip manufacturing back to America.”

Seiden, head of the Arizona chamber, pointed to the tight timeline to argue against additional regulations.

ﻗIf the EPA, for example, is adding regulations on ﻗ۵ that will drive up the cost, and that will make companies like TSMC say, ﻗWhy are we going to the U.S.?ﻗﻗ

Likewise, Shivakumar said, ﻗIt can take years for environmental clearances to take place. ﻗ۵ We just canﻗt afford to have those kinds of uncertainty and delay.ﻗ

Labor and environmental groups have expressed concern that their priorities will be steamrolled in the name of urgency. The Sierra Club, one of the nation’s largest environmental groups, urged Biden to veto the permitting bill.

ﻗThis bill would remove the last remaining federal lever to assess the impact of massive semiconductor fabs on drinking water, air quality, climate change, and community health,ﻗ Harry Manin, a Sierra Club legislative director, wrote in a news release.ﺡ ﻗPublic money should serve a public good, and fenceline communities deserve to know how theyﻗll be impacted.”

The group’s executive director, Ben Jealous, has highlighted microchip manufacturers’ legacy of pollution in Silicon Valley.

“If TSMC continues to cause public harm with public funds, it will demonstrate that the semiconductor industry learned nothing after peppering 23 Superfund Sites into Silicon Valley,” Jealous wrote earlier this year.

The scope of Arizona’s projects mirrors other global epicenters for semiconductor manufacturing, such as the Netherlands, where many chip-making machines are made, and Japan, which, like the U.S., is attempting a semiconductor revival of its own.

ﻗWe canﻗt get left behind on semiconductors,ﻗ Rogers said. ﻗItﻗs really our safety in the long run.ﻗ

This is one of a series of articles about Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. and the growth of the semiconductor industry in Arizona. Read more on azcentral.com.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=670d49a4e31246c4a2ca4803dad05ff1&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.usatoday.com%2Fstory%2Fmoney%2Fbusiness%2Ftech%2F2024%2F10%2F14%2Fsupply-chain-and-national-security-concerns-lead-to-big-focus-on-chips%2F74990486007%2F&c=7783365973778555712&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-10-14 03:53:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.