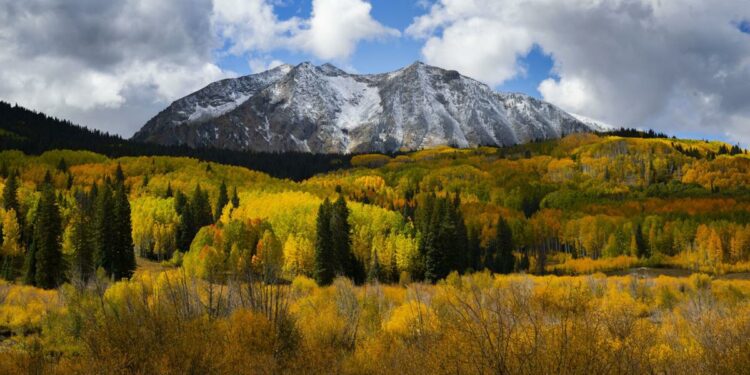

The sun spotlights the turning aspens on the westside of Kebler Pass near Crested Butte, Colo., Tuesday, Oct. 3, 2023. (The Gazette, Christian Murdock)

Christian Murdock/The Gazette

The summertime green we see on aspens is the result of chlorophyll, which is produced by warmth and sunlight. As the days get shorter and cooler come fall, chlorophyll production fades, clearing the way for the compounds to thank for the displays we seek.

We can thank always-present carotenoids and flavonoids. These provide leaves with their common yellow and less common orange and red hues. The showiest trees are the healthiest trees, and moisture plays a role there. Other factors: warm, sunny days that provide sugars, and cool nights (not freezing) that essentially trap those sugars in the leaf, spurring the anthocyanin reds.

2. Many trees represent one organism

Aspens turn to gold outside Gothic last fall.

Photos by Christian Murdock, The Gazette

When you’re looking at several trunks, you might think of a hand: several “fingers” growing from a “palm” underground. The “palm” is the root system, from which several trees or “fingers” grow. This is the most common, fascinating form of aspen reproduction: not by seeding, but by regenerative cloning.

The clones share genetics and physical characteristics; look closely at leaf shape and color — clones change in sync — and the bark texture and color. Clones might span a single acre or 100 acres. An individual tree might live a century, while scientists suspect its clone family might carry on for thousands of years.

3. The world’s largest organism

Aspens turn from green to yellow on Owl Creek Pass near Ridgeway, Wednesday, Sept. 28, 2022.

Christian Murdock, The Gazette

That’s the reputation of quaking aspen, populus tremuloides. It’s the reputation born by a pair of University of Colorado-Boulder professors who, in the 1990s, got the idea to argue populus tremuloides as the world’s largest organism, not armillaria bulbosa, “the humongous fungus.”

Those professors pulled up previous scientific descriptions of a clone in Utah’s Fishlake National Forest, now known as Pando (from a Latin word meaning “I spread.”) Pando reportedly covered 106 acres and more than 40,000 trees — what the professors estimated to weigh 13 million pounds altogether, much larger than the blue whale and “humongous fungus.” The professors concluded: “Quaking aspen, the most widespread tree species in North America, can now take its rightful place as an acknowledged giant among giants.”

4. It spreads far and wide

Quaking aspen is found south in Mexico, north in Canada, and much of the United States in between. Among the states, a U.S. Forest Service report notes aspen density is greatest in Colorado, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan and Alaska.

“Quaking aspen is native to and the most widely distributed tree in North America,” the report reads. “It occurs from Newfoundland west to Alaska and south to Virginia, Missouri, Nebraska and northern Mexico.”

The report found aspen living at several elevations, with their climates and habitats just as varied, from “moist upland woods, dry mountainsides, high plateaus, mesas, avalanche chutes, talus, parklands, gentle slopes near valley bottoms, alluvial terraces and along watercourses.”

5. Deep-rooted origins

Aspens show their colors along Last Dollar Road between Ridgeway and Telluride on Thursday, Sept. 29, 2022.

Christian Murdock, The Gazette

Your weekly local update on arts, entertainment, and life in Colorado Springs! Delivered every Thursday to your inbox.

Success! Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter.

Aspen’s ability to thrive in that variety contributes to another reputation: one of Earth’s longest-living organisms. “Older than the massive Sequoias or the biblical bristlecone pines,” the National Forest Foundation once noted.

That was based on popular estimates of Pando’s age, dating him — yes, he is male — back to the end of the last ice age, between 8,000 and 12,000 years ago. The age of the cloning organism has only been estimated, while the ages of individual, shorter-lived aspen trees are easier to determine. At more than 4,800 years, the bristlecone pine called Methuselah is known as the oldest, non-clonal tree in the world.

6. A pioneer species

Pioneer trees are those known to populate areas altered by fire, floods, landslides and other major impacts. Aspens do just that — notably in Colorado’s burn scars.

The Forest Service considers quaking aspen “an aggressive pioneer species” that “readily colonizes burned areas and can persist even when subjected to frequent fires.” The agency adds: “In the central Rocky Mountains, the extensive stands of aspen are usually attributed to repeated wildfires. It may dominate a site until replaced by less fire-enduring but more shade-tolerant conifers.”

7. A friend to many

Just as aspen is a pioneer species, it is a keystone species “attracting many birds, insects and mammals not found beyond its borders,” the Forest Service notes. “Next to streamsides, aspen are the most biodiverse forest ecosystems.”

Deer and elk depend on the trees through winter. While other deciduous trees go dormant, aspen continues to grow and provide those nibbling animals with the sugary, green layer found beneath the thin, white bark. Other animals big and small munch on young sprouts, those next generation of clones.

8. Facing threats

An overnight snowstorm dusts the Elk Mountains as the East River flows through the fall foliage near Gothic, Colo., Tuesday, Oct. 3, 2023. (The Gazette, Christian Murdock)

Christian Murdock/The Gazette

Munching from those animals and cattle poses grave threats to aspen, studies have found. When sprouts are eaten, the root system cannot spread — a point made by scientists concerned about overgrazing and overpopulated deer and elk herds.

They have other concerns. Thin bark makes aspen particularly susceptible to insects and disease. Drought and climate change pose other threats, at the center of what researchers have tracked as ”sudden aspen decline” across the West this century.

As Jeff Mitton, a University of Colorado-Boulder professor emeritus who studied aspen over his career, told The Gazette last year: “Resources are being drained faster in a warming climate. If (trees) are drought-stressed, they can’t do photosynthesis the way they want to, and that prohibits them from putting away the natural or regular amounts of energy. And so therefore over the years they’re depleting their energy source. Pretty soon, push comes to shove.”

9. The trees tell stories

However easy it is to carve on the thin bark — the hearts and initials are no wonder — it is illegal to carve aspen in national forests, the Forest Service emphasizes. But the agency has taken note of carvings dating back to the early 1900s.

These are carvings left by Basque sheepherders who came to work in Colorado. “These carvings are called arborglyphs, providing us information we could not find elsewhere,” the Forest Service notes.

The arborglyphs tell of hard, lonely times in the mountains: pictures of women and short messages. Read one translated during fieldwork across southwest and northwest Colorado: “Couldn’t pay me $1 million to come back here.”

10. Rooted in legend

“Aspis” in Greek refers to a shield. It is said warriors of lore made them from the lightweight wood. Aspen provided more than just physical protection, according to mythology.

People knew it as a “shield tree” to plant by a dwelling, reads an account by Trees for Life, a long-going organization working to rewild the Scottish Highlands. “Highlanders also thought of aspen as a magical tree,” the account continues. “An aspen leaf placed under the tongue would make the bearer more eloquent, traditionally a gift of the Faerie Queen.”

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66f18d8a21be44e29b0413386c906d32&url=https%3A%2F%2Fgazette.com%2Flife%2F10-facts-about-aspen-colorados-fascinating-tree-of-fall%2Farticle_5ed9e598-707e-11ef-8df7-3354c3a92a59.html&c=15252508865608129483&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-09-23 01:30:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.