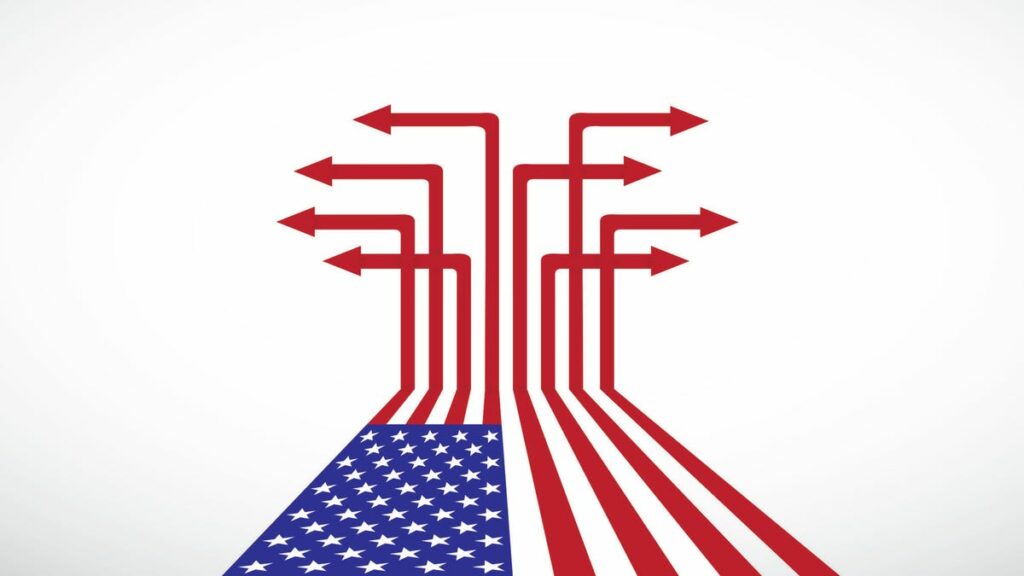

Red states are getting redder. Blue states are getting bluer.

Is it any surprise that our politics are getting hotter?

An exclusive USA TODAY analysis of the nation’s 3,113 counties shows a striking realignment since 2012 that has intensified the partisan leanings in states across the country, leaving only a handful where the outcome of the Nov. 5 presidential election remains in doubt.

The hardening of the country’s political lines has contributed to other consequences, too, including one-party control of the governorship and state legislature in 40 of the 50 states. That has led to a patchwork of sharply divergent laws across the country − even between neighboring states − on abortion rights, transgender care, the public-health response to the pandemic and other controversial issues.

“In this hyper-polarized era we’re in, I certainly am glad I’m in a blue bubble,” said Jane Crosson, 67, a retired pediatric cardiologist and a Democrat. When she moved from Baltimore to Durham, North Carolina, “we certainly picked it knowing that we were going to move to an area that was diverse but was, you know, solidly blue. So I have to admit that I chose to move to stay with my tribe in that way, if you will.”

Crosson was among those called in a national USA TODAY/Suffolk University poll exploring attitudes toward the deepening geographic divide in American politics. We conducted similar surveys in Arizona, Florida, Michigan and Pennsylvania, asking voters about their attitudes toward having political differences with others in their states.

“You see the homogeneity of counties becoming greater over, let’s say, the last 16 years of American politics,” said Ryan Enos, a political scientist at Harvard University who studies the intersection of politics, psychology and geography. That’s the result not only of people moving but also of shifting party allegiances by some voters and of turnover in the electorate, as young people and immigrants become eligible to vote.

What we say, what we do

Our poll found a push-and-pull.

Most Americans nationwide − a 55% majority − said it was very or somewhat important to them to live in a community that shared their general political views. Indeed, 7% said they had moved to a new community to be around more like-minded neighbors.

But an even larger majority, 60%, said it was very or somewhat important to them to live in a community with a diverse population, including those who don’t share their general political views. More than 1 in 10, 12%, said they have moved to a new community in search of more diversity.

On this, as on many things, there was a partisan divide.

Republicans were more likely than Democrats to say it was very important to be in a community with those who shared their general political views, 24% versus 18%. In contrast, Democrats were almost three times more likely to say it was very important to be in a community with diverse political views, 30% versus 11%.

The nationwide poll of 1,000 likely voters, taken Aug. 25 to 28 by landline and cellphone, has a margin of error of plus or minus 3.1 percentage points.

Those who have moved to more diverse communities included 18% of 18- to 34-year-olds; they are in a time of life when many young people are deciding where to settle. They also included 17% of Democrats but just 5% of Republicans.

Roger Sierra, 28, an independent from Miami who supports Republican Donald Trump for president, worried that the influx of out-of-staters was driving up housing prices and changing Florida’s politics. “The more people probably coming in that are different politically than me, it’ll probably end up like New York or California,” Sierra, who works in logistics for a home delivery service, said in a phone interview after being polled. “I cannot have left-leaning, straight ‘vote blue, no matter who’ people like that,” he said.

His family is considering moving to North Carolina, a state he called “a little bit of red.” But he added, “In the same way, when it’s like, ‘vote red or you’re dead,’ no. I need some stability.”

In the Arizona and Florida polls, the top reason cited for moving to those states was family considerations (37% and 47%), followed by jobs (32% and 22%). In Florida, the weather was also a major factor for 23%.

The USA TODAY/Suffolk polls of 500 likely voters in each state, taken by landline and cellphone, have error margins of 4.4 points. The Arizona survey was taken Sept. 21 to 24 and the Florida survey Aug. 7 to 11.

Politics played a role as well.

Fifteen percent of those who moved to Arizona said it was because the state was “better fit for you and your values.” Eleven percent of those who moved to Florida cited the same reason.

On the other side, 8% of those now living in Florida said they planned to move out of the state over the next four years. The top reason? “Politics/DeSantis,” a reference to conservative Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis, was volunteered by 40% of them.

“Overall, you have to wonder if these movements of people are nothing more than a mobilization toward a new sort of civil war,” said David Paleologos, director of the Suffolk Political Research Center. “Not the kind of civil war with militias and muskets, but a quiet separation from fellow Americans living in the state next door where life, laws, and political reality are worlds apart.”

‘A completely different country’

The interactive maps of how counties voted in the 2012, 2016 and 2020 elections show bright red and blue patches widening across the country. Many of the counties where the presidential vote was closely divided are becoming scarce.

“I’m in Ohio now, having moved from Maryland, and that was quite a thing,” said Liesl Semper, 58, a human-resources specialist now living in Akron. She is an independent who supports Democrat Kamala Harris for president. “Ohio feels like a completely different country, because Maryland is very, very, very blue and Ohio is not.”

“I moved for various other kinds of reasons,” she said, “and found myself in a completely different kind of space.”

Consider the numbers:

Seventy-three percent of counties became more partisan from 2012 to 2020, including 224 blue counties that got bluer and 2,050 red counties that got redder. (The disparity in number isn’t as stark as it sounds. The red counties were often in sparsely populated rural areas; the blue counties were often in densely populated cities and suburbs.)Overall, 40 states became more partisan − that is, states in which partisan leanings intensified in more than half the counties. The exceptions were Delaware, Hawaii, Maine, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, South Carolina, Utah and Vermont. Alaska wasn’t included in the analysis because it reports by election districts, not counties.Fewer than 1 in 5 counties, 19%, became less partisan over that time, trending less blue (264 counties) or less red (317 counties). In other words, by almost 4 to 1, counties became more partisan, not less so.Just 8% of counties changed colors, 50 red counties turning blue and 208 blue counties turning red.Even fewer ‒ 5% of counties, 161 of them ‒ were decided in 2020 by 5% of the vote or less, making them relatively competitive.

The sorting-by-state has made most of the country irrelevant to the fierce campaign now underway for the White House.

During the fall, both the Harris and Trump campaigns have sharply focused on just seven battleground states: Pennsylvania; Michigan and Wisconsin in the Upper Midwest; and North Carolina, Georgia, Arizona and Nevada across the South and Southwest.

The outcome everywhere else is considered all but settled.

That reflects an historic shift. According to calculations by political blogger Paul Radar, a majority of states, 33 of them, have voted for the same party in every presidential election over the past two decades, from 2000 to 2020. In the two decades from 1960 to 1980, not a single state voted for the same party in every presidential election.

The impact goes beyond presidential elections. It makes state and local elections less competitive, too, and reduces the opportunity and the need for conversation and cooperation across party lines.

“There’s reason to believe that one way to get people to cross divisions, whatever they are … is just being around people different than you,” said Enos, who directs Harvard’s Center for American Political Studies. That’s true of religious and racial differences, and some scholars believe the same forces could apply to partisan differences. “Having people interact is really important, and the more we’re separated across space, the harder that is to do.”

Crossing state lines

There’s a chicken-and-egg aspect to the trend.

The one-party control of most states − 23 now in Republican hands and 17 in Democratic ones − has led to purely conservative policies in some red states and purely liberal ones in some blue states. In turn, some Americans say those conservative and liberal laws have prompted them to consider leaving places where they feel politically isolated or going to places where their views are empowered.

“Part of my move to California was safety and security of being around people that are more liberal and progressive, absolutely,” said Kristina Calvert, 39, a Democrat who moved from Chicago to Sacramento, though she said it felt “weird” to think about politics in that way.

Routt County in Colorado, one of the states trending bluer, shares a border with Carbon County in Wyoming, which is trending redder. In 2020, Democrat Joe Biden carried Routt County by 27.6 percentage points; Trump carried Carbon County by 53.5 points.

The two Mountain West states could hardly have enacted more sharply different policies over the past few years.

The Wyoming Legislature last year passed, and Republican Gov. Mark Gordon signed, the first law in the nation specifically banning abortion pills. The state also outlawed all abortions except in cases of rape, incest, or the serious risk of death or irreparable physical harm to the mother. (The laws have been put on hold pending legal challenges.) In March, Gordon signed a law barring a range of gender-affirming medical care for transgender minors.

Next door, the Colorado Legislature in 2022 passed, and Democratic Gov. Jared Polis signed, a law that blocks any governmental restrictions on abortion. The state was the first to require private insurance companies to cover transgender care, and it also allows young people to come from elsewhere to access gender-affirming care.

That is, to cross state lines.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=6704689f7f214f05b176740111b5c87c&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.usatoday.com%2Fstory%2Fnews%2Fpolitics%2Felections%2F2024%2F10%2F06%2Fred-states-redder-blue-bluer-politics-sorting%2F75374267007%2F&c=12527498553164958681&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-10-05 22:04:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.