The Gaylord Opryland Resort is an artificial oasis in the barrens of northern Nashville, Tennessee. Colossal palm trees reach toward the glass ceiling in the hotelŌĆÖs verdant conservatory, sealing the grounds in a perpetual equatorial humidity. A few Disneyland-esque waterfalls crash into the rippling stream that circles the miniature shopping concourse below; it includes what the resort refers to as the ŌĆ£only Jack Daniels restaurant in the world.ŌĆØ This has traditionally been a setting for country music, particularly the historic Grand Ole Opry. But on this summer day, it provided a jarring contrast to an entirely different kind of event. As hundreds gathered nearby, Tara Petito stepped up to a microphone and imagined out loud what she might have said to Brian Laundrie, the man who murdered her daughter.

ŌĆ£He robbed our daughter, our beautiful Gabby, of her life, her future. He robbed her of the chance to ever know what itŌĆÖs like to walk down the aisle with the love of her life, to bear children, to grow old,ŌĆØ she said, grief flickeringŌĆöthen smolderingŌĆöin her throat. ŌĆ£He is a horrible excuse for a human being. If Brian was alive today, any words out of his mouth would be lies.ŌĆØ

The disappearance of Gabby Petito was one of the most pervasive crime stories of 2021. The 22-year-old was traveling across the United States over the summer in a camper van with her fianc├®, Laundrie, with the intention of documenting their journey in blooming, hashtaggable snapshots on #vanlife Instagram. But Petito vanished during the trip, stirring up a whirlwind of speculative press, condemnation of police malpractice in domestic violence cases, and anger at the elisions of social media. PetitoŌĆÖs body was discovered in a Wyoming park three weeks later, and in October, LaundrieŌĆöwho had since disappeared himselfŌĆöwas found dead by a self-inflicted gunshot wound, alongside a notebook in which he admitted to the crime.

The frenzy that consumed GabbyŌĆÖs murder turned the mixed Petito familyŌĆöher stepmother Tara, her stepfather Jim, and her biological parents, Nichole and JoeŌĆöinto celebrities. They have thousands of social media followers and have been featured in countless glossy magazine interviews and cable specials.

Now here they were in Nashville, at CrimeCon, one of many stops of a live true-crime circuit that subsumes families like these for years after the unthinkable happens to someone they love, providing them a forum to recount their sorrow and suffering to eager audiences. Even three years after GabbyŌĆÖs murder, everything the Petitos will say at CrimeCon is treated like breaking news. By the end of the convention, recaps of the familyŌĆÖs appearances will be published by Fox News and CNN.

CrimeCon, now in its eighth year, fashions itself as the singular nexus for the large and loosely defined true-crime community, aiming to summon a fandom that exists primarily onlineŌĆöthrough twisting subreddits, gumshoeing podcasts, and lengthy comment threads on the 20/20 Facebook pageŌĆöinto physical space. The convention drew 6,000 guests this year, an uptick from the 5,000 who attended 2023ŌĆÖs event in Orlando. Tickets started at $229 and are tiered between standard, gold, and ŌĆ£platinumŌĆØ packages, with the latter offering fast-track lanes, private lounges, and exclusive memorabilia from the eventŌĆÖs ŌĆ£talent,ŌĆØ many of whom are the family members of murderers and murder victims alike. The CrimeCon imprint has been successful enough that Red Seat Ventures, the company behind the conventionŌĆöas well as a larger portfolio that includes flagship podcasts from Bari Weiss and Megyn KellyŌĆöis set to expand. It has already made landfall in the United Kingdom, and this winter, it will take to the high seas for the annual CrimeCruise.

Luke Winkie

The patrons get their moneyŌĆÖs worth. Over the course of a single weekend, NashvilleŌĆÖs CrimeCon clienteleŌĆöyoung and old, but overwhelmingly white and femaleŌĆöwill orbit through a variety of keynotes and panels. Nancy Grace and Chris Hansen are on the docket, as are the authors of whodunits, like Aphrodite Jones. Elsewhere, youŌĆÖll find emergent stars, like the pseudonymous hosts of the ludicrously popular Small Town Dicks media brand, and Anthony Ames, a former NXIVM member who now co-hosts the true-crime podcast A Little Bit Culty.

But looming above the rest of the field, haunting every corner of this event, are the victims and the people connected to them. John Ramsey, father of JonBen├®t Ramsey, is a headliner, as are Denise Huskins and Aaron Quinn, the couple who were implicated, then exonerated, in a wild kidnapping scheme that was recounted in the hit Netflix true-crime docuseries American Nightmare. Further down the bill youŌĆÖll find Summer Shiflet, the sister of Lori Vallow Daybell, who received a life sentence for the murder of her children and another woman. On the second day of the conventionŌĆöa few hours before Shiflet was scheduled to speakŌĆöDaybellŌĆÖs husband would be sentenced to death for the crimes. Undaunted, Shiflet took the stage. ŌĆ£When I heard those words, it was everything I needed to hear,ŌĆØ she said to a packed house in the main theater, in an exclusive response to the news.

The convention does not compensate its guests for their appearances. Most of them are expected to pay for their travel and lodging. Still, these victims flock to CrimeCon to make their bereavement public and consumable. They will spend the weekend addressing their life-altering tragedies in a variety of different panels, Q&A sessions, meet and greets, and cocktail hours. They will be flagged down by badge-holders concealing morbid curiosities. They will be wreathed with condolences, pose for pictures, and autograph the inside covers of their memoirs. All the while, they will be reacquainted with the terrible way theyŌĆÖve become famous.

Tara Petito is, unsurprisingly, a superstar in this world. Laundrie ŌĆ£murdered our daughter, drove back to his familyŌĆÖs home, and then went on vacation while Gabby lay cold, out in the wilderness, with the grizzly bears,ŌĆØ she said during her session. ŌĆ£Thinking about the pain our baby girl had to endure is truly agonizing. Visualizing her final moments over and over again is a pain I wish on no one. The trauma it causes is unexplainable. Sometimes I feel like IŌĆÖve downed a bottle of pills, but IŌĆÖm completely sober. All because of that piece of garbage.ŌĆØ

This was CrimeCon in its basic essence: powerful, tender, and undeniably lurid. It left me with a question I couldnŌĆÖt stop asking in Nashville: What on earth brings people like Petito here? She has repeated this story many times since her daughter was murdered. She has sat down with Dr.┬ĀPhil and Sean Hannity. She has told People magazine that she feels as if her daughter is sending her messages from the heavens. Yet, still, sheŌĆÖs once again reliving the worst event of her lifeŌĆönot just as a victim and a survivor, but as a CrimeCon dignitary. I embarked on a surreal weekend to find out why.

Logan Guo

A few hours before Tara PetitoŌĆÖs panel, right after CrimeCon opened its doors, guests were funneled into one of OprylandŌĆÖs immense auditoriums, which would serve as the conventionŌĆÖs marquee dais for the rest of the weekend. The lights dimmed over a phalanx of identical chairs, all pointed in the direction of two gargantuan projection monitors hovering over a spartan stage. CSI-flavored yellow text beamed across the screens, underlaid with the urgent clacking of a laptop keyboard. ŌĆ£Through all the tales of triumph and tragedy, we are here to remind you that these arenŌĆÖt just stories,ŌĆØ read the text. ŌĆ£These are real families. Real lives.ŌĆØ

What followed was a medley of cable news clips, edited together in warp speed, providing a recap of the past year in crime. The Rust shooting was mentioned, for which Alec Baldwin had not yet been cleared, along with the potential unmasking of Tupac ShakurŌĆÖs killer and the long-awaited release of Gypsy Rose Blanchard. The audience cheered the heroes and heckled the villains, right on cue, with an obvious fluency in all order of unsolved mysteries. The Delphi murders case, for which a trial is finally imminent, got a huge ovation. The montage rounded out with a series of heartening conclusions: criminals busted, missing people recovered, truths revealed. The show had come to life. EminemŌĆÖs ŌĆ£Lose YourselfŌĆØ poured out of the speakers.

Luke Winkie

Joe Petito, TaraŌĆÖs husband, would later tell me he had been scared to come to CrimeCon the first time. After watching the introduction video, I understood why. Joe had feared that people were attending this convention to gawk at him, focusing on, in his words, the ŌĆ£gory detailsŌĆØ of his daughterŌĆÖs killing. The whole Petito family grasped the bitter irony of their presence, he said. Jim Schmidt, GabbyŌĆÖs stepfather, recalled the years his wife had spent as a true-crime junkie, basking in the enthralling puzzle of a provocative murder, savoring the careful distance from the pain. ŌĆ£You see the stories and are like, ThatŌĆÖs not realŌĆöhow did that happen?ŌĆØ he told me. ŌĆ£And before you know it, youŌĆÖre living it.ŌĆØ

Joe has come around, though. This is now the second CrimeCon the Petitos have attended. Joe treats the weekends like a vacation. ŌĆ£People are looking for inspiration; theyŌĆÖre looking for help with their own lives,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£I was pleasantly surprised by how giving the people here are.ŌĆØ

The panel that featured Tara was called ŌĆ£Finding a Voice: Victim Impact Statement Readings.ŌĆØ Typically, victim-impact statements are read in court before sentencing occurs. The idea is to allow survivors a chance to color a perpetratorŌĆÖs crimes with their own accounts, pairing clinical procedure with visceral experience. Five women had volunteered to speak at this panel, two of whom were reciting the same statements they had delivered at the trials where their own perpetrators met justice. The other three were never afforded the opportunity in court. So they intended to use this venue, and its ticketed audience, to conjure an alternate timeline where they could look into the eyes of the person who had caused them so much misery.

One of the volunteers was Mo Silva, the daughter of Deanna Butterfield, who was raped and murdered by William Huff, the Bay Area prowler, in 1987. Her body was found in the picnic area of a Berkeley park. Her killer wasnŌĆÖt sentenced until 2018, some 30 years later. Silva was choking back tears even before she began reading at the lectern. She had been just 4 years old when her grandmother called her to the living room and informed her that her mom was sick. Silva suggested a trip to the pharmacy to get medicine that might heal her. Then her grandmother told her the truth.

ŌĆ£My heart sank, and I began to cry,ŌĆØ she said. There was a long pause, and Silva began to visibly wither under the lights, matching the stifled sobs that slipped out of the audience. ŌĆ£Just as I am now. Because I knew I would never see her again.ŌĆØ

By the time Silva and I spoke after her speech, she had regained her composure. She was wearing a silver butterfly pendant, joining some that float down a half-sleeve tattoo on her right arm. (Her mom had had a small butterfly tattoo on her chest.) The panel was SilvaŌĆÖs one and only CrimeCon duty. She had depicted her suffering, with excruciating clarity, for a crowd of onlookers who could never understand, and now the job was complete. I had the same question for her as I had for the others: Why would anybody do this to themselves?

ŌĆ£CrimeCon is focused on the front part of crime, but weŌĆÖre forgetting about the end, and thatŌĆÖs the aftermath and the victims,ŌĆØ she told me. ŌĆ£Attendees look at all these cases and want to hear about all the details, and then their interest stops. But that isnŌĆÖt the end. ThatŌĆÖs just the beginning of a new phase that sucks. So if youŌĆÖre going to do all of this, let the people see the messy part. Let them have access to people like me. Let them feel the rawness.ŌĆØ

Away from the ballroom, in the conventionŌĆÖs central gallery, exhibitors awaited guests. Aging mystery authors reclined behind gory paperbacks; representatives of collegiate criminal justice programs stood ready to recruit aspiring investigators; podcasters prepared promotional souvenirsŌĆöpins, brochures, and stickersŌĆöall splayed out like Halloween candy on their tables. Court TV, the former cable channel that has since been relegated to digital broadcasting, had one of the largest booths in the building, equipped with a slab of cardboard printed with the question ŌĆ£WhatŌĆÖs Your True Crime Obsession?ŌĆØ (By the end of the weekend, it was covered with sticky notes bearing all sorts of answers: ŌĆ£Serial Killers + Culty Things,ŌĆØ read one. ŌĆ£All of It!ŌĆØ said another.)

Standing alone amid the pulp was a booth belonging to the National Center for Victims of Crime, a nonprofit that helps rehabilitate families languishing in the aftermath of a tragedy. Ren├®e Williams, an advocate and the organizationŌĆÖs executive director, distributed to those passing by a sheet detailing ŌĆ£eight simple rulesŌĆØ for being an ŌĆ£ethicalŌĆØ true-crime fan. The bullet points were boiled down to lean, punchy mantras: Do No Harm. Respect Boundaries. It was Williams who had orchestrated the afternoonŌĆÖs victim-impact statement readings, a project that she hoped would remind CrimeConŌĆÖs attendees of the trauma that a highly scrutinized mystery can inflict. Williams was happy with how the readings had gone, but she had fretted about the optics of the panel for weeks before the convention. ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm always worried if something is exploitative,ŌĆØ she said. ŌĆ£Are we putting something out for someoneŌĆÖs entertainment?ŌĆØ

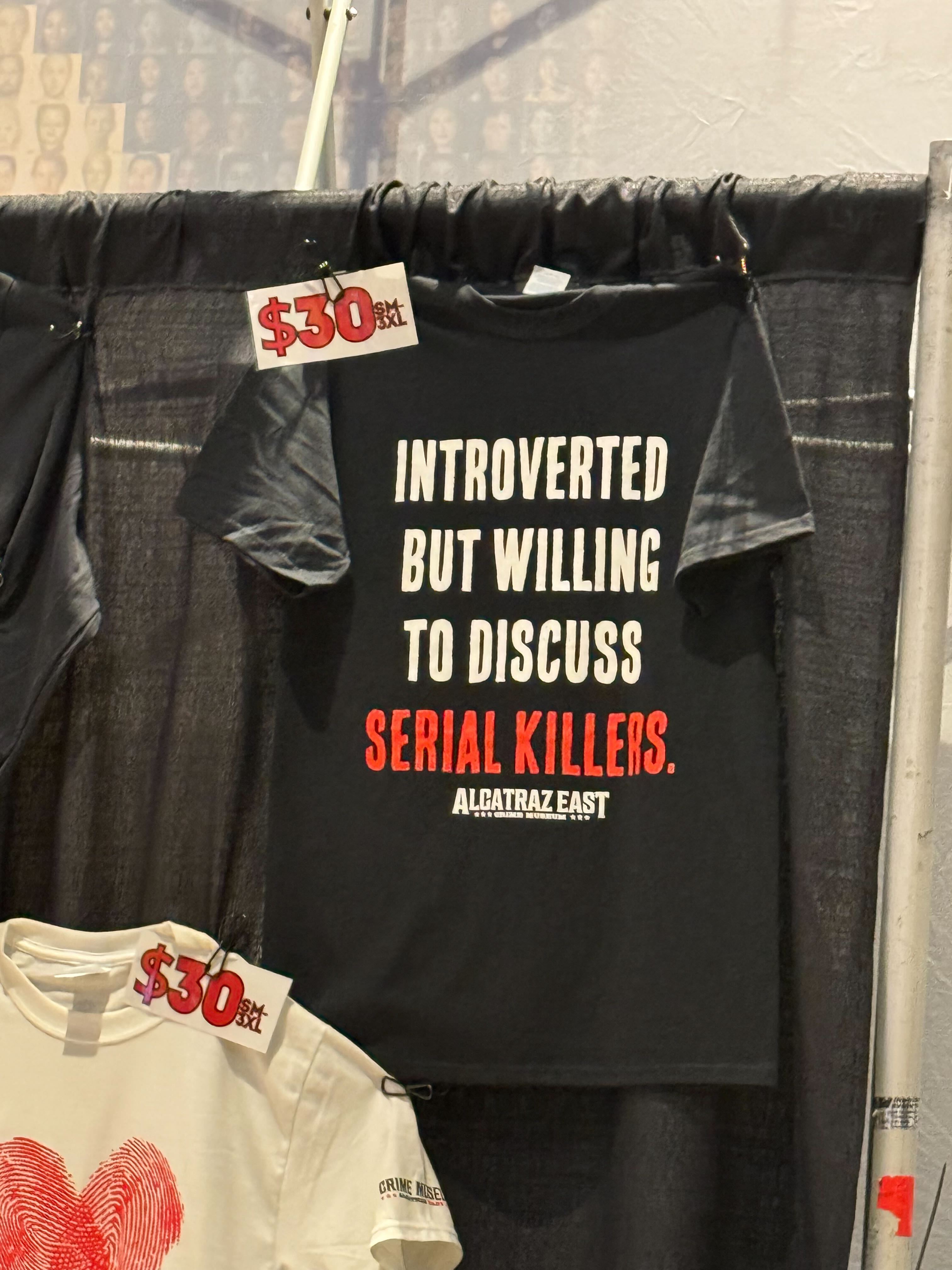

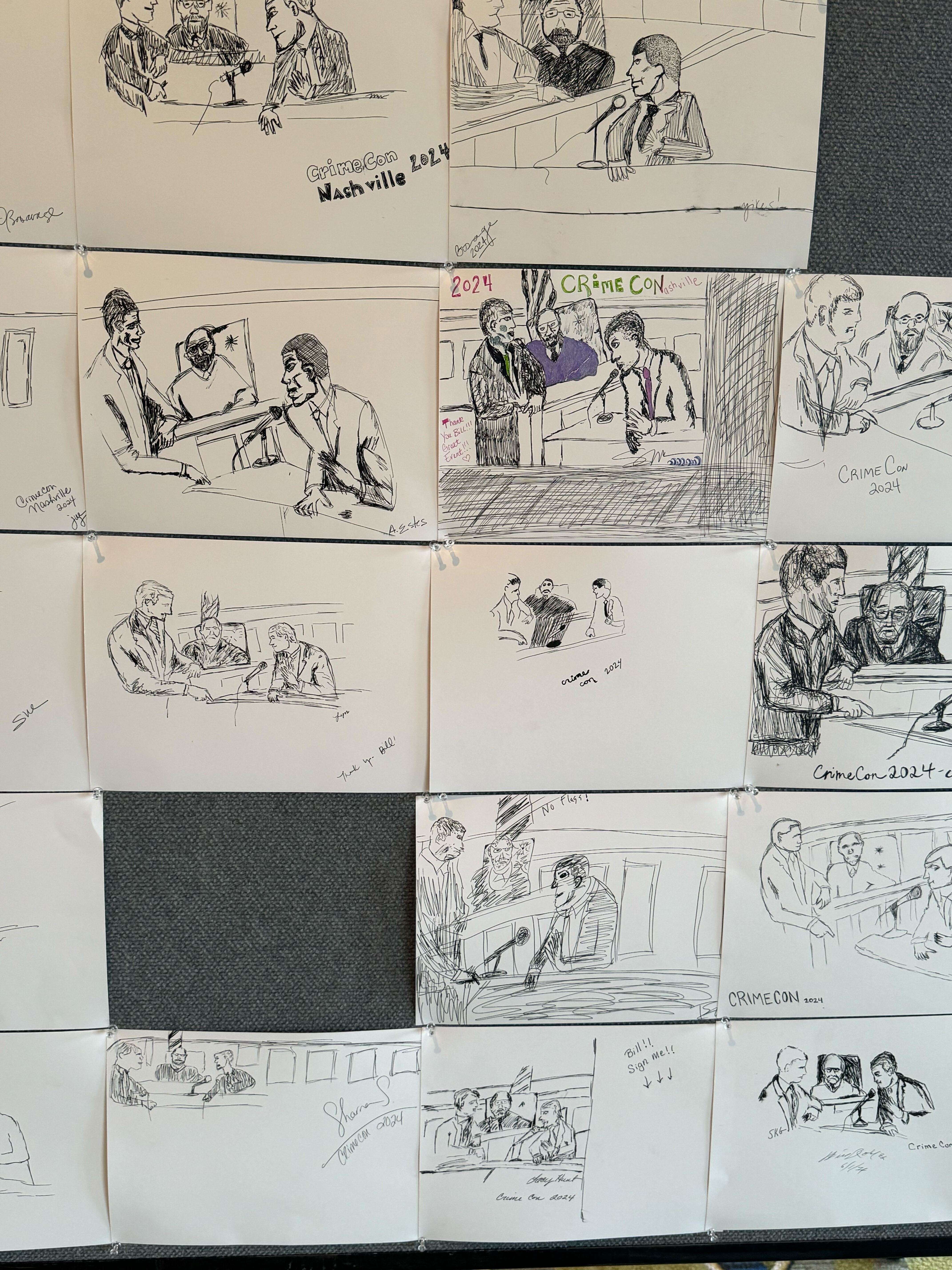

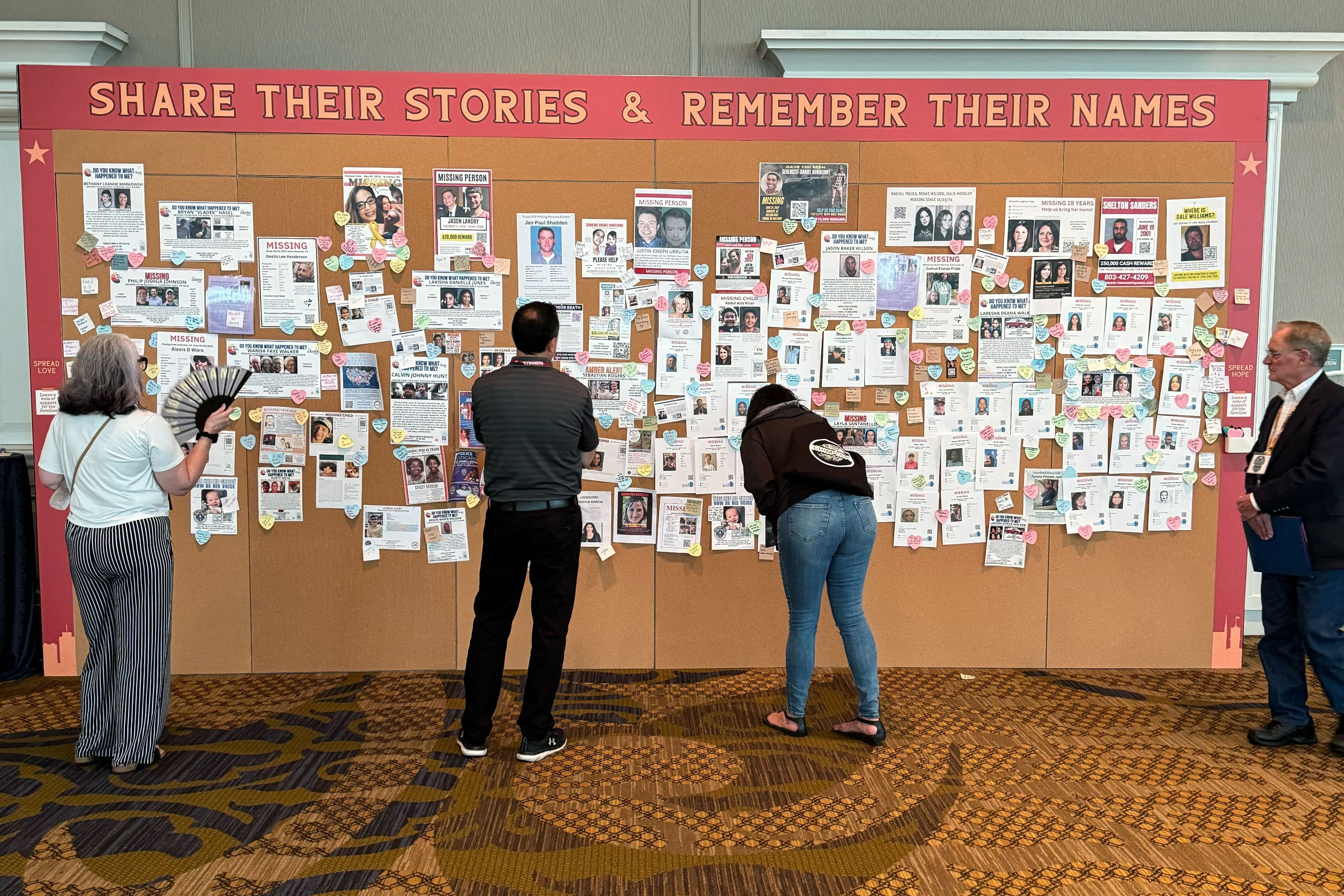

The National Center for Victims of Crime has for years had a presence at CrimeCon, but initially, Williams said, her colleagues in the victim services sphere werenŌĆÖt happy about those appearances. ItŌĆÖs a fair point. Could a commercial enterprise profiting in part off suffering performed by the invited victims sustain credible advocacy? The exhibition hall was a testament to the eventŌĆÖs enormous contradictions. The Black and Missing Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to raising awareness for uncracked cases involving victims of color, had a well-staffed studio near the main entrance. But the end of the promenade was marked by the conventionŌĆÖs official merch shop, hawking T-shirts printed with slogans like ŌĆ£Talk Motive to Me,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Catch Killers Not Feelings,ŌĆØ and perhaps the biggest hit at the convention, ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm Only Here for an Alibi.ŌĆØ Later, a select group of badge-holders would be gathered for a ŌĆ£Sketch and SipŌĆØ event hosted by renowned courtroom artist Bill Robles, who has immortalized everyone from Harvey Weinstein to Charles Manson at the defendantŌĆÖs table. The party would step to their easels, wineglasses in hand, and learn what it takes to portray a striking cross-examination of a predator.

How do you reconcile one with the other? As far as Williams was concerned, you donŌĆÖt. To her, the only perspectives that matter belong to the bereaved, and they had made the trip to Nashville of their own accord.

ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm a victim advocate. IŌĆÖm not their mother. I have to let them make decisions as adults,ŌĆØ she said. ŌĆ£I need to trust their instincts.ŌĆØ

This was the third year in a row John Ramsey had attended CrimeCon, and he still wasnŌĆÖt quite sure why anyone would pay for a ticket. In an hour, he was due to take the conventionŌĆÖs main stage, opposite author Paula Woodward and a box of tissues, for a high-profile panel titled ŌĆ£Searching for Truth.ŌĆØ His 6-year-old daughter JonBen├®tŌĆÖs notorious murder and all that came out of it have given him plenty of time to contemplate the enduring fascination with the case.

Luke WInkie

ŌĆ£Some of the attendees are these amateur detectives who treat it like a real-life board game,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£They stop me in the halls. They say they only came to the convention just to meet me. IŌĆÖm almost embarrassed by it. IŌĆÖm not that great. IŌĆÖve not done anything spectacular.ŌĆØ

Ramsey is 80 years old, and JonBen├®t has been dead for nearly three decades. Nobody at CrimeCon has been in the spotlight longer than he has. RamseyŌĆÖs media portfolio includes appearances on Dr. Phil, The Dr. Oz Show, and a memorably uncomfortable Barbara Walters interview in 2000, in the still-simmering aftermath of the crime. He has also published two booksŌĆöthe first defending himself from those who suspected his familyŌĆÖs involvement in the killing, and a second reflecting on the combined grief of JonBen├®tŌĆÖs murder and the death of his wife Patsy from ovarian cancer in 2006. This has all helped ensure that the lurid interest in JonBen├®t has never faded.

ŌĆ£I have a file on my email account for the crazy people. I put all of that stuff in there,ŌĆØ said Jan Rousseaux, RamseyŌĆÖs third wife, whom he married five years after Patsy died. Rousseaux hadnŌĆÖt been anywhere near Colorado during Christmas 1996, but missives from the dedicated, and the unhinged, bombard her inbox all the time.

ŌĆ£The other night, his phone kept vibrating. Bzzt. Bzzt. Bzzt. Finally, I got up because I thought someone we know might be in trouble,ŌĆØ Rousseaux said. ŌĆ£But no, it was a woman in Canada, sending a series of photos and textsŌĆö11 of themŌĆösaying, ŌĆśI am your daughter. I am JonBen├®t.ŌĆÖ┬ĀŌĆØ

Ramsey believes that this is a good problem to have. Police investigations tend to be malleable to scrutiny, and if you trust his accountŌĆöthat a roving invader broke into his house, tortured and murdered his daughter, and stashed her body in the basementŌĆöthen you must also trust that Ramsey is being honest when he says that he is doing everything in his power to focus the fraught nature of his celebrity on the objective of finding JonBen├®tŌĆÖs killer. Ramsey makes sure to read all the unhinged emails that Rousseaux detailed, even the ones that are erratic and dissertation-length. ŌĆ£YouŌĆÖre always looking for that little nugget that isnŌĆÖt public information,ŌĆØ he said.

ŌĆ£I want to clear the cloud,ŌĆØ Ramsey said when asked why he keeps saying yes to things like CrimeCon. ŌĆ£My family needs the cloud removed. ItŌĆÖs not going to change my life at this point, but for them, it will.ŌĆØ

In Nashville, I learned that Ramsey is correct about the advantages of his stardom. Maggie Zingman, a 69-year-old from Oklahoma whose pink horn-rimmed glasses protrude from curtains of silver hair, would do anything to swap places with him. She has a slain daughter too. Her name was Brittany Phillips. Zingman often wears an oversize pin displaying PhillipsŌĆÖ high school portrait. On this day, itŌĆÖs dangling heavily from her collar.

In 2004, Phillips was raped and murdered in her Tulsa apartment. She was 18, and she was buried on her 19th birthday. Investigators never came up with a suspect, nor did any national reporters sniff around to ramp up the pressure. So, when PhillipsŌĆÖ case went cold, Zingman took matters into her own hands. She plastered her SUV with pictures of her young daughter and printed the number of a tip line along its doors. Zingman has been driving across the country, on and off, since 2007, searching for a lead. That odyssey had now brought her to CrimeCon. Standing next to Zingman was a life-sized cardboard cutout of her daughter. ŌĆ£Do You Know Me?ŌĆØ reads the text near her head. ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm the Girl Next Door.ŌĆØ

Zingman is not a featured speaker at this yearŌĆÖs event. She will not be appearing on any panels or conducting any book signings or meet and greets. Therein lies the problem. Despite her best efforts, the slaughter of Brittany Phillips has never achieved nearly the same resonance as other American tragedies. This fact has left Zingman alone with the most horrible of mortal sensations: a twinge of envy as she watches the zeitgeist wash over the bereaved mothers who happen to have a more famous dead daughter.

Luke Winkie

ŌĆ£Do I get jealous? Yes. Is it hard? Yes. But I canŌĆÖt be ashamed about it. ItŌĆÖs human nature. I see the Petito family talking to all of these people: Chris Hansen, Paul Holes, John Walsh. National news attention is the only thing thatŌĆÖs going to change my case and if my story could get in their hands,ŌĆØ Zingman told me. ŌĆ£There are thousands of us out there. IŌĆÖm from middle America. My daughter had gone away to college. She had a chemistry scholarship. She was beautiful. But thatŌĆÖs too normal.ŌĆØ

Candice Cooley, the mother of Dylan RoundsŌĆöa Utah teen whose murderer pleaded guilty to the crime earlier this yearŌĆötold me at the conference she had been in ZingmanŌĆÖs position until she got ŌĆ£lucky,ŌĆØ in the grimmest sense of the word. CooleyŌĆÖs calls to her local news stations had gone unreturned for weeks after her sonŌĆÖs disappearanceŌĆöuntil one day she began to weave his biographical details into her plight. Rounds had left home at 17 to start a farm on his grandfatherŌĆÖs property. The color of his life was enough to overcome the algorithm. Suddenly, RoundsŌĆÖ story was everywhere.

ŌĆ£We gave him a brand. Gabby was the blogger, and Dylan was the farmer. Unfortunately, thatŌĆÖs what it takes,ŌĆØ Cooley said. ŌĆ£Our Facebook group exploded to 20,000 people after that, and thatŌĆÖs when the media grabbed it.ŌĆØ She was wearing a gray sweatshirt embellished with the logo of her foundation, DylanŌĆÖs Legacy: two stalks of wheat crisscrossing under a sunflower. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs almost like you have to market your missing child,ŌĆØ she said.

In 2023, when some of the details surrounding RoundsŌĆÖ murder were still murky and hot on the tabloid circuit, CrimeCon sprang for CooleyŌĆÖs flight and hotel so she could attend the convention. Cooley was assigned to a meet-and-greet session that she found unpleasant and dehumanizing. ŌĆ£I had people coming up to me that I donŌĆÖt know, telling me that they loved me, and they want to hug me, and that they love my son so much,ŌĆØ Cooley said. ŌĆ£I felt like a circus monkey,ŌĆØ she added. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs like youŌĆÖre put on display. Like, Oh, you paid $300 extra just to meet me.ŌĆØ

Lately, CooleyŌĆÖs friendships with the other big names on the true-crime junket had strengthened, to the point where the promise of a reunion with them was one of the main reasons she traveled to Nashville. Cooley has grown particularly close with the Petitos. Now that their cases have been mostly settled, their shared focus has turned to families of missing children who have never been showered with the same attentionŌĆöabsorbing, then reflecting, the spotlight.

It was here that I began to understand one part of the enduring gravitational pull victims experience with CrimeCon. Even as the Tara Petito panel focused on the still-raw aftermath of her daughterŌĆÖs murder, Jim Schmidt and Joe Petito, GabbyŌĆÖs stepfather and father, respectively, appeared on another panel, which spotlighted Indigenous women who had been disproportionately victimized by violent crime. Sitting next to them onstage was Vangie Randall-Shorty, a Navajo woman whose son Zachariah Juwaun Shorty was abducted and killed in New Mexico by an unknown person in 2020. Joy Sutton, the panelŌĆÖs host and the woman behind the podcast Untold Stories: Black and Missing, asked Joe what he made of ŌĆ£missing white woman syndrome,ŌĆØ a term used to describe how preoccupied the news apparatus can become with the disappearance of someone who fits GabbyŌĆÖs precise demographic background. Joe replied with several factors that he thinks led to the media circusŌĆöa gap in the tabloid cycle and, yes, perhaps the color of her skin.

It was extraordinary to watch him analyze the horrific death of his daughter from such a vantage point, considering how heavily the loss still weighs on the Petito family. Jim told me that since Gabby went missing, pretty much everything makes him cry. ThereŌĆÖs a cheesy Publix commercial in particular that reveals the extent of his heartbreak. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs about a stepdad and a daughter,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£It goes through the years, and the daughter is saying, ŌĆśThanks, Dad.ŌĆÖ High school graduation: ŌĆśThanks, Dad.ŌĆÖ┬ĀŌĆØ JimŌĆÖs voice trailed off, and his eyes began to well up.

ŌĆ£ThatŌĆÖs what happens!ŌĆØ Joe said. ŌĆ£I walked into a room where my wife was watching 90 Day Fianc├®. I sat down to watch just for a few minutes. The first thing I saw on the TV happened to be a dad walking his daughter down the aisle. And I started bawling.ŌĆØ

If the two of them are to share this domainŌĆöwith the specter of their catastrophe waiting to pounceŌĆöthen perhaps it makes sense that the Petitos are doing whatever they can to give this new life meaning, or at least to be dutiful custodians for other bereaved parents who have recently joined, in JimŌĆÖs words, ŌĆ£the club.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs validating,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£Everybody knows our story. But weŌĆÖre here alongside other victims, to elevate them. And thatŌĆÖs how we always frame those sessions.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs our purpose,ŌĆØ Joe said.

At the victim-impact sessionŌĆöthe same one where Tara Petito and Mo Silva spokeŌĆöthere was also Kerri Rawson, the famous daughter of the BTK killer, Dennis Rader. She was there to break some unsettling news in the case.

After reviewing RaderŌĆÖs coded diaries as part of an ongoing police investigation to uncover more of his crimes, she discovered evidence that she, too, had been sexually abused by her father. The revelation lined up with a buried memory. Rawson was 2 years old when the incident happened, she believed. She has a faint recollection of a large man hulking over her childhood bedroom, which contextualized the lifelong problems sheŌĆÖs had with her neck.

Rawson said she confronted Rader with the charges in prison, where he is serving 10 consecutive life sentences. He told her it was a ŌĆ£fantasy.ŌĆØ

This latest twist in the BTK saga quickly made headlines across the true-crime media ecosystem. Reports of the horror immediately popped up on NewsNation and the New York Post.

A couple of days later, in a bit of whiplash, I came to see Rawson sign some books in the conventionŌĆÖs meet-and-greet room. She sat in front of a paperboard backdrop stamped with the CrimeCon logo; yellow caution tape stretched over a black-and-white thumbprint.

Their DaughterŌĆÖs Murder Consumed America. What TheyŌĆÖre Expected to Do Now Is Unfathomable.

When I Was 13, the Unimaginable Happened. I Had to Grow Up Anyway.

We Were Supposed to See Taylor Swift in Vienna. We Learned a Surprising Lesson About Human Nature Instead.

The Right Has Settled On Its Most Potent Attack Against Tim Walz. It WonŌĆÖt Work.

The heaviness of the material didnŌĆÖt affect the mood in the lobby. Rawson was breezy and hospitable. One of the first fans in line to meet her was Candy Griffin, a realtor from Texas. She had started following RawsonŌĆÖs writing career on Facebook and Twitter after they first met in the VIP lounge of last yearŌĆÖs CrimeCon, where the two had hit it off immediately. They have had remarkably similar lives, Griffin thought. Both have lived in the exact same region of rural northeastern Kansas. She connected with how Rawson wrote about loss. Griffin is surprised that they didnŌĆÖt meet ages ago.

ŌĆ£My father wasnŌĆÖt a serial killer,ŌĆØ Griffin said. ŌĆ£But there are a lot of things that interlink us.ŌĆØ

The dissonance continued. On Sunday morning, the final day of the convention, the booths in the exhibition hall were already being packed into boxes. Most of the victims had caught flights out of Nashville, and by the afternoon, CrimeCon had vanished without a trace. But in its dying embers, you could find a brand-new placard set up in the Opryland foyer: CrimeCon 2025 in Denver had just been announced. Tickets are on sale now.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66bc889dc72f43d3bdc46b5e9634c777&url=https%3A%2F%2Fslate.com%2Flife%2F2024%2F08%2Fcrime-murder-mystery-petito-btk-jonbenet-interview.html&c=11172037838142370785&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-08-13 22:35:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.