ON JULY 10, 1971, A CLASSIFIED U.S. SATELLITE attempted to return a mysterious “data package” to Earth by ejecting a capsule over the Pacific Ocean. But the capsule’s parachute failed, and the canister slammed into the water with a perilous 2,600 Gs of force. It then sank to the seafloor, some 16,400 feet beneath the waves.

What followed was one of the most logistically complex, politically daring deep-ocean search and recovery missions in American history, as well as the world’s deepest undersea salvage. Led by the U.S. Navy and the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), the mission’s goal was to recover data from America’s most advanced spy equipment at the time—the KH-9 Hexagon satellite package, which contained thousands of top-secret photographs—before the Soviet Union could.

Now declassified, the Hexagon was a marvel of engineering. Built before the days of digital imaging and processing, this school-bus sized apparatus, unofficially known as “big bird,” was almost like a movie camera in orbit. The Hexagon’s multiple recovery “buckets,” or capsules, contained film captured by a panoramic camera, which allowed for advanced global positioning and data gathering. During the Cold War, the Hexagon’s main purpose was wide search: between 1971 and 1986, 19 Hexagon missions surveilled a collective 877 million square miles of Earth’s surface, including the vast territory of the former Soviet Union (for context, the total surface area of our planet is about 197 million square miles). Hexagon reconnaissance satellites were the largest (and last) U.S. intelligence satellites to return photographic film to Earth.

CIA

The main internal parts of a Hexagon film capsule. The KH-9 Hexagon was declassified in September 2011. The following January, it was put on public display alongside its predecessors, the KH-7 and KH-8.

“Imagine standing at the launchpad in 1971; the U.S. is about to launch a satellite that’s larger and more complicated than any previous space vehicle ever launched into space,” says James Outzen, director of the Center for the Study of National Reconnaissance (CSNR) at the NRO. “With it, the United States had the capability to continuously image large swaths of Russian territory, gathering intelligence about the locations of Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile sites, airfields, and even objects as small as a foot-and-a-half in size,” he explains. “Now, imagine that on its very first mission, fully a quarter of this secret imagery is lost at sea.”

The stakes were high: the Hexagon satellite’s unexpected splashdown meant that not only was a piece of U.S. intelligence vulnerable to saltwater and sea sediment, but that its recovery could very well tip off Soviet spies. Meanwhile, determining the bucket’s precise location would be arduous. Harder still, no attempt had yet been made to salvage an object from such great ocean depths. The mission’s success was purely theoretical, and this would be an interesting test case for the U.S. Navy.

When it was completed in the mid-1960s, the Trieste II was the U.S. Navy’s most advanced deep-sea submersible, making it suitable for the job. The bathyscaphe’s descent and ascent were controlled by adjusting its buoyancy relative to its displacement in the surrounding seawater. Unlike a submarine, which is restricted to the surface of the ocean, the bathyscaphe could dive to the deepest known spot in the ocean (the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, at 35,800 feet below sea level). In order to accomplish this feat, several tradeoffs in design had to be made: namely, the cabin had to be built strong enough to withstand tremendous hydrostatic pressures of 16,000 pounds per square inch, but still scaled to a reasonable weight and size. The submersible would need to not only descend to the ocean floor, but salvage the wreckage below.

Trieste II in San Diego, 1979. Beyond the deep-sea spy satellite recovery mission, the bathyscaphe has also recovered bits of wreckage from the lost submarine Thresher, a U.S. Navy nuclear-powered attack submarine that sank off the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts in 1963.

Over the next few weeks, the NRO consulted Eastman Kodak film and the company that had built the satellite. The organization coordinated across federal entities, including the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Air Force and the CIA; various teams set to work determining point of impact, prevailing sea currents, ocean floor conditions, temperature, wind speed, and sunlight levels, developing a strategy to catch the apparatus.

The team first attempted its salvage with a net. When that failed during land and sea trials, they turned to a “hay hook”: basically, a giant hook and claw that could maneuver and envelop an object, then hoist it from the Trieste II to surface ships. Plans called for the ocean-going tug USS Apache to tow the USS White Sands—a World War II-era auxiliary repair dock—to an operating area with the Trieste II stored inside. The ship also needed to be able to lift a 55-gallon drum, properly refrigerated and insulated, filled with seawater and the capsule.

The “hay hook” in the open position.

In September 1971, steadily deteriorating weather halted several of the initial planned dive operations. Growing concern that heavy seas might damage the Trieste II required pilots to reduce the towboat’s speed to two knots per hour (the minimum needed to maintain control). But this put the vessel in danger of running out of fuel as it battled wind gusts and strong undertows. Security concerns were also paramount, since the salvage operations effectively established a precise area of interest to the Soviet Navy (though records conflicted about whether they had positioned a ship near the sunken Hexagon at the time).

Unrelenting foul weather and the need to dry-dock the Apache for repairs postponed salvage operations until the spring. Finally, on April 25, 1972, following a two-hour descent and a three-and-a-half-hour search, the U.S. team spotted a tangled mass of metal on the seafloor. After another hour of careful maneuvering, the hook was at last in position to retrieve the film stacks.

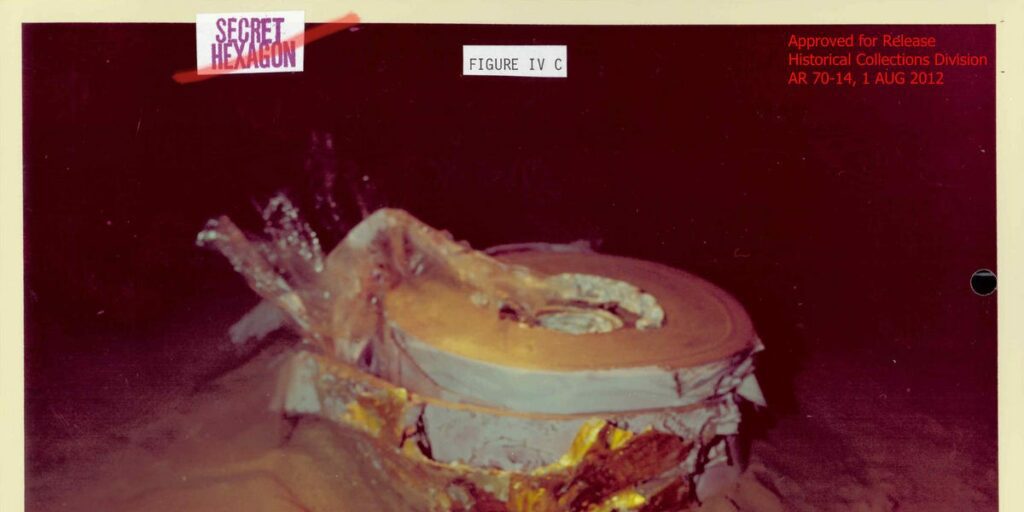

Film stacks inside the recovery hook shortly after rising from the ocean floor on April 25–26,1972.

The submersible held motionless for several minutes to allow silt and mud to drain, then began its careful ascent. Suddenly, pieces of film began to break apart, disintegrating into clouds of reddish brown dust that dotted the ocean swells.

By the time the Trieste II (DSV-1) neared the surface around 2:30 a.m. on April 26, shreds of film were precariously hanging off the lines of the hook. A five-person dive team raced to the scene in small boats with floatation devices that they attached to the remaining wreckage on the ocean floor; miraculously, the divers managed to retrieve three out of four buckets of film stacks. The secrets had at last been found—though not without significant damage to the canisters.

Dive Deeper ⬇️

Somehow, despite being subjected to extreme pressure underwater and a high-velocity impact, the film had survived. Against staggering environmental and technical odds, the United States was able to carry out one of the boldest operations undertaken in intelligence and deep-sea exploration history.

Admiral Elmo R. Zumwalt Jr., then Chief of Naval Operations, presented the team in charge of the recovery with a Meritorious Unit Commendation for “this singularly significant achievement,” which “provided the United States Navy with the capability to conduct deep-ocean search, location, and object recovery operations in an estimated 80 percent of the sea areas on Earth.”

The Trieste II continued deep-ocean operations—some public, some classified—until the ship was deactivated in 1984. The Trieste is now on permanent display at the Naval Undersea Museum in Keyport, Washington, and once top-secret files tell its story.

Adrienne Bernhard is a Los Angeles-born, New York-based freelance writer and former assistant to the deputy editor at The New Yorker. She has written for the Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal, the BBC, Smithsonian, The Atlantic, the Boston Review, and New Criterion, among others.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66e0d0f8ce7248e9a6e86a07d3d9df2b&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.popularmechanics.com%2Ftechnology%2Fa62135509%2Fus-hexagon-spy-satellite-salvage%2F&c=6737099562906544835&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-09-10 09:24:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.