Get our Insights on a range of topics, highlighting WPR’s original analysis, sent to your inbox.

Venezuela’s regime remains as the last holdout of South America’s original Pink Tide. But the Bolivarian revolution that began under former President Hugo Chavez has transformed into an economic and humanitarian disaster under his successor, Nicolas Maduro. The attempt to dislodge Maduro and replace him with Juan Guaido in 2018 gained the support of the U.S. as well as governments across the region and the world. But that effort flagged, and Guaido was ultimately replaced as the leader of the political opposition, which is now struggling to maintain relevance ahead of a presidential election now scheduled for July.

Major advances in the region are also in danger. Colombia’s fragile peace process faltered after former President Ivan Duque’s hostility to the deal resulted in half-hearted implementation of its measures. Petro has promised to revive the deal with the FARC while seeking a broader peace with other insurgencies and armed groups that still operate in the country, but so far his efforts have delivered disappointing results. Meanwhile, the illicit drug trade is booming, as is organized crime, even as corruption continues to flourish. The coronavirus pandemic added another immense challenge to South America’s public health systems and economies. And now the spike in food and energy prices due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is poised to introduce further economic upheaval, with potential political consequences.

Perhaps more than questions of right and left, though, what most characterizes South America today is a sense of instability and democratic fragility. Peru’s Castillo was removed as president in December 2022 after a shambolic 18 months in office that culminated in an attempted self-coup, setting off protests and a political crisis that continues to threaten the country’s democracy. Followers of Bolsonaro stormed government buildings in Brasilia after Lula’s inauguration in what appears to have been a bungled coup attempt. And in Ecuador, Noboa won a snap election called by Lasso to end the country’s political paralysis. A region that until recently was a haven of democratic stability now seems to be struggling to find its way.

WPR has covered South America in detail and continues to examine key questions about what will happen next. How will the economic fallout of great power competition between the U.S., China and Russia affect the region’s political and economic landscape? What’s ahead in efforts to address Venezuela’s political and humanitarian crises? And how will Washington approach relations with the region’s new wave of leftist leaders to counter Russian and Chinese influence? Below are some of the highlights of WPR’s coverage.

Our Latest Coverage

Russia’s Economic Coercion Should Be a Wake-up Call for Latin America

A standoff between Ecuador and Russia over a proposed arms transfer to Ukraine last month foreshadows how global competition among great powers may play out in Latin America moving forward. If the region doesn’t learn from the episode, it will find itself vulnerable to much larger forms of economic coercion over the coming decade.

Politics

Right-wing and center-right governments still control Ecuador, Uruguay and Paraguay. In part a reaction to the years of leftist rule, the right’s rise in the late 2010s was also fueled by the emergence of major corruption scandals that tainted politicians and parties across the region. But the left has demonstrated resilience as a political force, even as a wave of anti-incumbent sentiment seems to be the most decisive factor driving voter behavior.

Security and Drugs

The drug trade is booming, particularly in Colombia, where cocaine production is at an all-time high. That has fueled violence and put state legitimacy at risk across swathes of the continent, including most recently the previously peaceful Ecuador. Some leaders, desperate for a solution, are responding with growing militarization. Meanwhile, labor advocates, Indigenous leaders and civil society remain vulnerable to political violence.

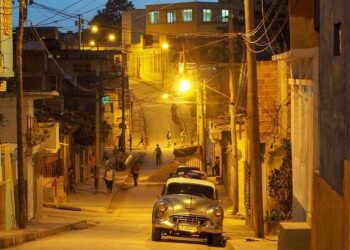

Venezuela

The humanitarian crisis in Venezuela is deepening, even as the standoff between Maduro and the opposition seems to have been won by the Chavista regime. Though his claim to the presidency was backed by much of the continent, along with Washington, Guaido failed to dislodge Maduro. Now Maduro, who oversaw the country’s economic freefall, appears to have decisively sidelined the opposition, in part due to the support of the Venezuelan military.

Trade and Economic Development

Moscow and Beijing have been eager to increase their economic ties to South America, leveraging the unease that was caused by former President Donald Trump’s mixed messages to the region. Washington has pushed back, warning that the two powers are looking to sow disorder on the continent. Meanwhile, South American economies, already hard-hit by the coronavirus pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, are in for more turmoil due to China’s economic slowdown.

Corruption

Corruption scandals, which proliferated under the left-wing administrations of the Pink Tide, helped drive the ascent of the right. But the scandal involving payoffs by the Brazilian construction giant Odebrecht across the region also took down center-right politicians. Corruption remains high on the list of voters’ grievances, even as the pandemic increased both the opportunities for and the costs of graft and impunity. Unless it is brought under control, corruption might ultimately undermine the region’s democratic institutions.

Read all of our coverage of South America.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in May 2019 and is regularly updated.

Related

Source link : https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/pink-tide-south-america-politics-economy/

Author :

Publish date : 2024-03-12 03:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.